What are sunspots?

Sunspots are cooler parts of the Sun’s surface caused by massive changes in the Sun’s magnetic field.

Although sunspots are a phenomenon that has been known about for at least several thousands of years, our understanding of them has been far less certain.

Since they moved across the surface of the Sun, some astronomers originally thought they might be small planets in orbit, while others suspected they were simply imperfections within telescopes.

What causes sunspots?

The generally accepted theory – proposed by H. Babcock in 1961 – suggests that they are caused by changes in the Sun’s magnetic field.

Because the rotation period of the Sun is faster at the equator than towards the poles, a 'differential rotation’ is created. This causes the magnetic field to become increasingly 'wound up’ as the Sun rotates, stretching the magnetic field between the poles and the equator.

This stretching causes tubes or tunnels to form in the magnetic field. The loops rise and break the surface, preventing convection of the superheated gases underneath. The result of this is the creation of areas of lower temperature, which are visible as dark spots.

How big are sunspots?

Sunspot sizes vary enormously. For a spot to be visible without magnification, it must be approximately twice the size of the Earth. By contrast, the largest group on record, from 1947, would have needed about 141 'Earths’ to cover it.

The length of time they appear for also changes. Some last for just a few hours, but in 1943 a sunspot was recorded as lasting around six months.

The 11-year cycle

The number of sunspots follows a cyclical period of about 11 years, something that was first noted by Heinrich Schwabe in 1843.

There are two ways of plotting this cycle. One is to simply count the number of spots and by plotting the numbers against a time scale a periodicity can be determined. Another is by means of the so-called 'Butterfly Diagram’. At the beginning of a new sunspot cycle, sunspots appear mainly close to the Sun's north and south poles. As the sunspot cycle progresses, more sunspots appear closer to the Sun's equator.

Disappearing sunspots

Although the 11-year cycle has been consistent in modern times, there was a period between 1645 and 1715 when there were virtually no spots at all. This period is known as the 'Maunder Minimum’, after the British astronomer who discovered it from the records in 1890. This might itself be a part of a cyclical period, although it is impossible to be know since it has only been a few hundred years and thus it is too soon to be sure.

Do sunspots affect Earth?

Scientists have not found any measurable connection between the number of sunspots on the Sun or any other measure of the solar cycle and the day-to-day variation in the weather on Earth.

Photographing sunspots

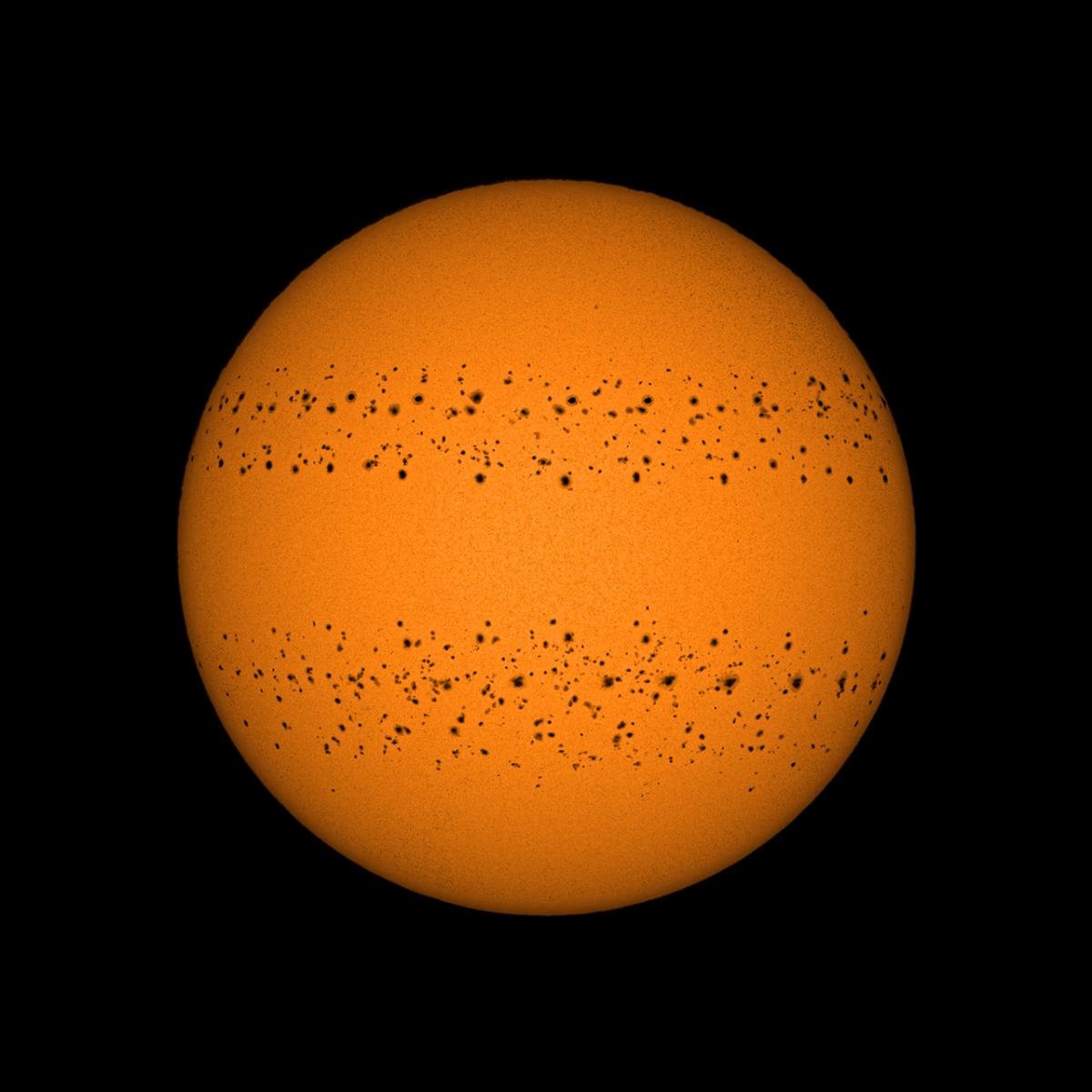

This is A Year in the Sun, an image by Soumyadeep Mukherjee which was entered into Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2022.

It features hundreds of individual photographs blended into a single shot, showing how sunspots move across the surface of the Sun over the course of a year.

"I imaged the Sun for 365 days between 25 December 2020 and 31 December 2021, missing just six days during this period," Soumyadeep says. "The project started with the aim of recording the journey of a single sunspot across the solar disc, but I managed to continue it for a year. I blended the images to create a single shot, which records the rise of Solar Cycle 25.

"A total of 127 active regions appeared on the Earth-facing solar disc (AR 12794–AR 12921) during this phase and the image shows all of them. The sunspots create two bands on the solar disc, around 15–35 degrees north and south of the equator and gradually start drifting towards it – a phenomenon known as Spörer’s law."