The Great Plague was one of the worst disasters in London's history. Samuel Pepys's diaries provide a fascinating insight into how Londoner's dealt with this tragedy.

The Great Plague

In the summer of 1665 Londoners were dying from a horrible and familiar disease. Although it was a regular visitor to the city, bubonic plague had returned with a vengeance. By the end of the year, the ‘Great Plague’ had taken the lives of almost 69,000 people, although the true figure was probably nearer 100,000 – almost a quarter of London’s population.

Bubonic plague was a frightening and dreadful disease. Beginning with fever, the bacterial infection was characterised by painful swellings, or ‘buboes’, in the neck, armpits and groin. These could be accompanied by vomiting, muscle cramps and coughing up blood.. More often than not it resulted in death, usually within a week of the first symptoms.

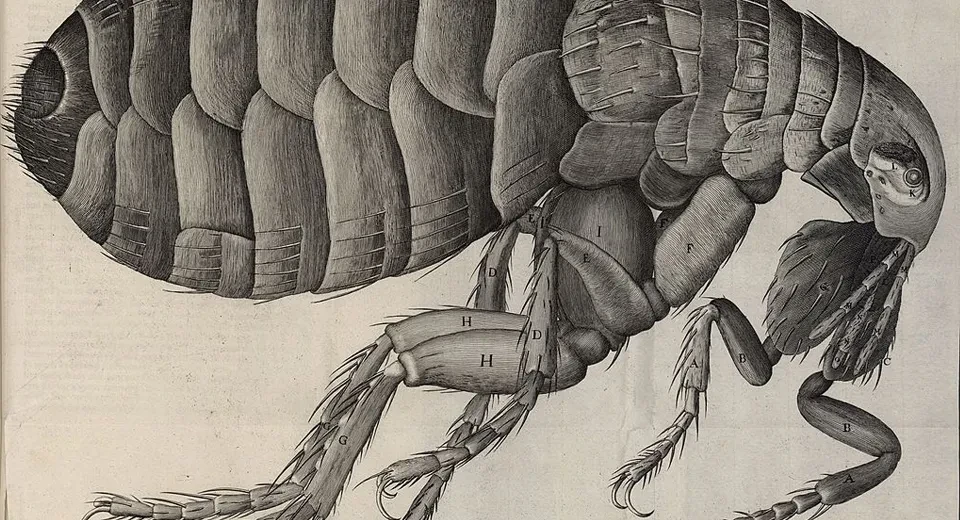

In 1665 nobody understood what caused the disease or how it was spread. Bad air was blamed, as were the dogs and cats that roamed the city. In fact it was rats, hosts to the disease-carrying fleas, which infested the cramped and dirty streets of London that facilitated the transmission of the plague between its residents.

‘Great fears of the sickenesse here in the City’

Samuel Pepys first mentioned the plague in his diary in October 1663 when he recorded a major outbreak in Amsterdam and feared for its spread to England. His anxiety was well founded, for by the spring of 1665, plague had reached these shores, and in June Pepys wrote, ‘to my great trouble, hear that the plague is come into the City’.

Nevertheless, unlike many of those who had the opportunity, Pepys remained in London for much of that year, and even after he and his employer were forced to relocate to Greenwich in the late summer, he commuted by river from there to his home in Seething Lane near the Tower of London and visited other parts of the capital. During this time his diary and letters report a rapidly worsening situation, a devastated population, and his own worries, grief and fears.

‘The towne grows very sickly’

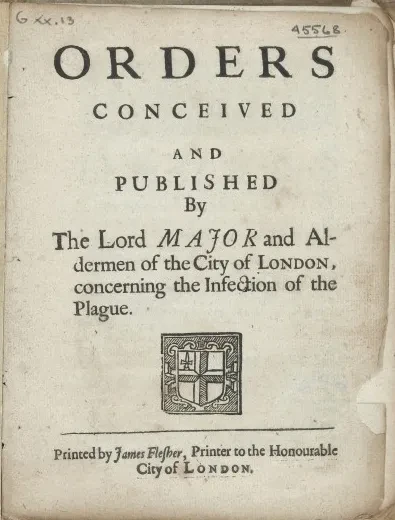

Pepys is the best source for understanding the desperation and frustration of officialdom in dealing with a catastrophe that they didn’t fully understand. In early June he described his first encounter with their futile measures to control the spread, ‘I did in Drury-lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “Lord have mercy upon us” writ there – which was a sad sight to me’. As with previous outbreaks, it was decreed that any house where plague was identified should be shut up for 40 days with the family inside, marked with a cross and be guarded by watchmen.

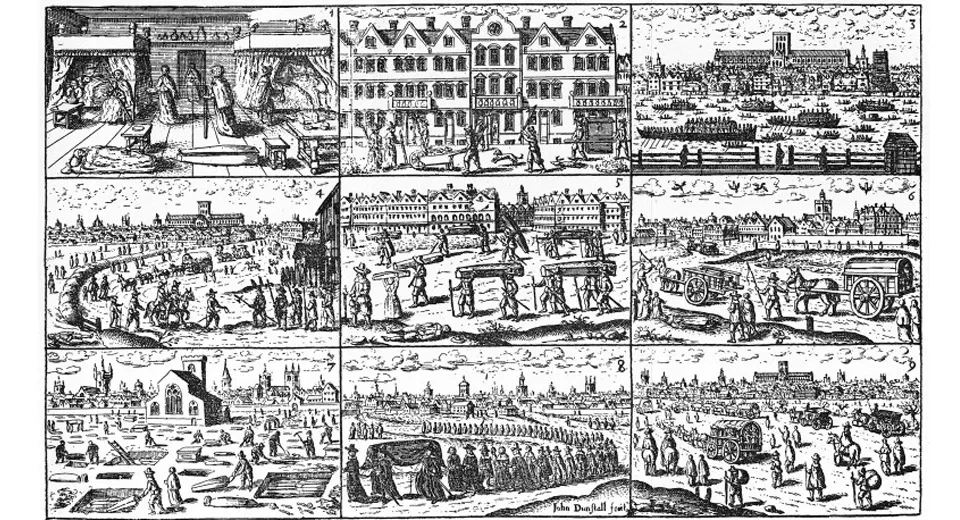

As plague moved from parish to parish Pepys described the changing face of London-life – ‘nobody but poor wretches in the streets’, ‘no boats upon the River’, ‘fires burning in the street’ to cleanse the air and ‘little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells’ that accompanied the burial of plague victims. As the bodies piled up, Pepys wrote to a friend, ‘the nights (though much lengthened) are grown too short to conceal the burials of those that died the day before’. He also writes in his diary about the desensitization of people, including himself, to the corpses of plague fatalities, ‘I am come almost to think nothing of it.’

‘My apprehensions of it great’

Despite his reluctance to abandon the city, Pepys clearly feared catching the plague. Ominously he set his papers in order and rewrote his will, chewed tobacco that was wrongly thought to keep the disease at bay and refused to wear a new periwig fearing that it could be made from hair ‘cut off of the heads of people dead of the plague.’ Yet despite his worries Pepys also appears to have had a morbid fascination with the disease, keeping a compulsive eye on the official weekly mortality bills and making a voyeuristic visit to the plague pit in Moorfields when the epidemic was at its peak.

So why didn’t Pepys succumb to the plague? Although the disease wasn’t as contagious as people feared, it is possible that Pepys was one of those people who were naturally unattractive to the flea’s bite. Three years earlier he mentioned in his diary an occasion when he shared a bed with a friend and casually remarked ‘that all the fleas came to him and not to me.’ Yet despite his own fortune, the disease did have a personal impact on Pepys: he laments the loss of friends, relatives, colleagues, his brewer, his baker and his physician to the disease.

‘I have never lived so merrily’

Against this backdrop of pestilence, fear and apprehension, however, much of Pepys’s life in 1665 went on as usual. He still worked at the Navy Office, continued his adulterous liaisons, celebrated his cousin’s wedding, and pursued many of his interests. Surprisingly the year brought much opportunity and wealth Pepys’s way and, as the plague subsided, he wrote in his final diary entry for the year, ‘I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague-time’.