Discover some of the surprising entries recently discovered in the medical records of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital.

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich was the main clinical site of the Seamen’s Hospital Society (now Seafarer’s Hospital Society), founded to bring relief to sick and injured seafarers of all nations. The HMS NHS: The Nautical Health Service project was launched in 2021 to transcribe the many thousands of entries in the hospital admission registers between 1826 and 1930. The amazing work of the HMS NHS volunteers will provide researchers with opportunities to explore more than one hundred years of medical care provided at the centre of maritime Greenwich.

A lesser-known Melville

One of the most surprising finds made by our volunteers has been a patient identified as one of the sons of the American writer Herman Melville (1819-1891). Stanwix Melville, aged 18, born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, was admitted to the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital with bronchitis on 1 April 1870.

Herman Melville is of course best known for Moby-Dick, a novel about a dramatic whaling adventure, first published in 1851. Melville’s writing was informed by his own experiences as a young merchant seaman, and Stanwix developed a similar yearning to make long voyages away from home. These feelings may have become acute following the tragic death of his elder brother Malcolm by a self-inflicted gunshot in 1867.

Stanwix’s first taste of the sea was arranged through the contacts of his seafaring uncle, Thomas Melville, then governor of the Sailors’ Snug Harbor on Staten Island. He joined the crew of the American barque Yokohama (1859) and departed from New York for Shanghai in April 1869. For reasons unknown, he later made use of an opportunity to jump ship, probably while the Yokohama was at Shanghai in July 1869.

Stanwix arrived in London at the end of January 1870 on the barque Joseph Sprott (1866), owned by J.B. Sprott of Liverpool. The ship’s master John C. Dixon was later required to give evidence in relation to events on 27 September 1869, when the Joseph Sprott was in collision with another homeward-bound vessel in the Manipa Strait. The case ended badly for Dixon, as the arbitrators decided that damages should be paid to the owners of the other vessel which had been forced to dock for repairs at Singapore.

The next voyage of the Joseph Sprott had more disastrous consequences. In March 1870 she left London for Hong Kong, with Dixon replaced as master by Robert Rice. In February 1871 the homeward leg of the voyage between Manila and Liverpool was almost complete when the ship was wrecked on the southern coast of Ireland. She was driven ashore and lost with all hands at Long Strand, west of Galley Head, County Cork.

Sailing vessel wrecked on rocks by William Lionel Wyllie (PAE2920).

There can be no suggestion that Stanwix was involved in this shipwreck, as he was admitted to the Dreadnought in the month after the Joseph Sprott had commenced the voyage. He must have crossed the Atlantic soon after being discharged on 25 May 1870, because he appears in the returns of the United States Federal census conducted on 22 June in the same year, back home with the Melville family in New York. In later records we can find him working as a dentist in San Francisco in 1876 and he died in that city from tuberculosis, aged only thirty-six, in 1886.

Biographies of Herman Melville don’t usually contain much information on his son Stanwix. However, an article entitled The Leaving Years: The Short, Sad Story of Stanwix Melville, by Christopher Benfey, first published in ‘The New York Review of Books’ in 2010, can be found online here.

Below decks on the Dreadnought in 1851

Staying with the topic of literary heroes, it is worth exploring the connections between the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital and Charles Dickens (1812-1870). A description of a tour around the hospital ship was published in his weekly magazine, Household Words, in August 1851, and the same article appeared in various newspapers.

Dickens was struck by the contrast between what would have been the appearance of the ship fitted as a commissioned warship HMS Dreadnought (1801), and her present stripped-back condition. The emphasis was now on cleanliness and the promotion of wellbeing:

‘…There is no capability of firing a 32-pounder. Where would you make the breeching fast; where would you secure the gun-tackles? Then, the decks have been cut out in places to make skylights, and to let the fresh river air come flowing through; and there are warm pipes, which diffuse a genial heat along the decks.’

A small waterline model of HMS Dreadnought (1801), from a scenic depiction of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, originally exhibited at Cremorne Gardens, Chelsea, and presented to Greenwich Hospital in 1858 (SLR2745.11).

Dickens mentions various artefacts and scientific specimens seen during the visit. An old piece of glass from a cabin skylight, scrawled over with the names of naval officers, was a souvenir from the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. A botanical collection was found in the cabin of an assistant surgeon, likely to have been Dr Augustus H. Churchill (1811-1895). Meanwhile, a rather gruesome group of skulls, which in the context of modern medical ethics would be highly questionable, formed part of a museum collection on the ship:

‘…A kind of trap-door on the deck of [the dispensary] opens, and we descend to the museum. Here we behold a collection of skulls of all nations -a geographical Golgotha which is to the ethnographer of illimitable interest. Each skull is wrapped up in paper, and duly labelled.’

The skulls were a product of the scientific pursuits of Dr George Busk (1807-1886), surgeon on the ship at this time. He joined the staff of the Seamen’s Hospital Society as an apothecary in 1830, was appointed surgeon in 1839, and visiting surgeon from 1854 onwards. An obituary notice for Busk in The Journal of The Royal Anthropological Institute in 1886 describes how his role on the Dreadnought was the genesis of a particular collecting habit:

‘Mr Busk’s taste for anthropology appears to have been first roused by the opportunities for its study afforded by the seamen of the most varied races and nationalities who became patients at the Dreadnought Hospital; and a small collection of typical crania which he then formed, furnished the materials for commencing those investigations into the distinctive characters of the skulls of races, which will always be associated with his name…’

For those interested in reading more, an obituary notice with information on Busk’s research can be found here on The Royal Anthropological Institute website. We know that a small museum continued to be maintained at the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, as its location is shown in a plan of the ground floor made in 1892. Does anybody know what became of the collection of crania?

A Guernsey-born seafarer

One of our volunteers was excited to find an ancestor named Beaumont Hodsoll de Putron among the entries in the Dreadnought registers. De Putron was born on the island of Guernsey in 1850, first went to sea in 1864, and qualified as a master mariner in 1875. His employment on various sailing and steam vessels often took him far away from home, yet he also fathered eight children.

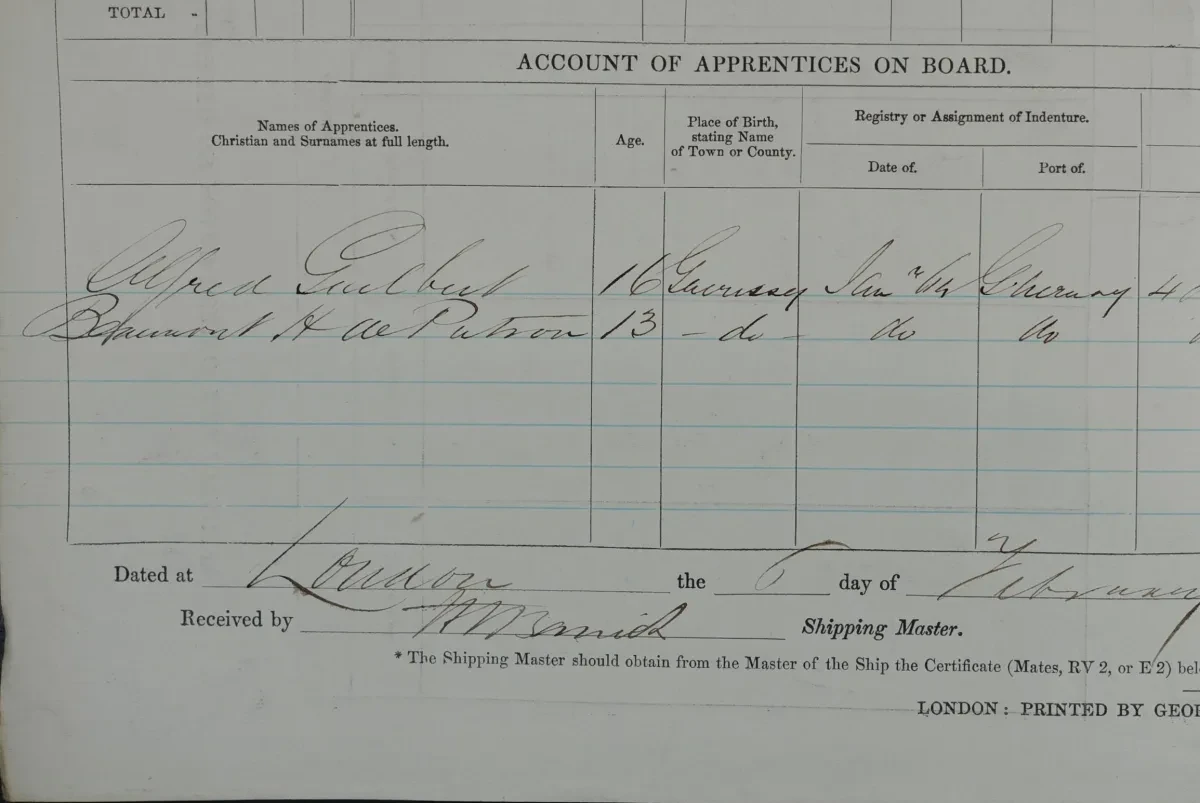

Among the relevant records in the archives at Greenwich, there is a crew agreement from the first voyage of the full-rigged ship Channel Queen (1864), built to trade with ports in the Indian Ocean and Far East. De Putron appears as an apprentice, aged thirteen. The homeward voyage from Colombo terminated at London in February 1865.

On a subsequent voyage, the Channel Queen visited the southwestern coast of India. In a long letter written by the ship’s master Hilary Marquand to his wife Louisa, dated 20 February 1866, there is an account of how five of the crew, including Marquand and De Putron, narrowly escaped death when the ship’s jolly boat capsized during an attempt to cross the bar at Mangalore. As Marquand clung to the oars of the overturned boat, buffeted by the heavy surf, he saw that their situation was perilous:

‘I was most anxious about little de Putron, poor little fellow, it made me sad to think he should drown. I did not then know he could swim, but it appears he can swim like a fish. We all could swim but one, but being so far from shore we could not have saved our lives in such breakers.’

Details of apprentices entered on a crew agreement for the Channel Queen of Guernsey, Official No 44944 (RSS/CL/1865/1555).

Luckily, the second mate back on the ship had been watching as the drama unfolded, and immediately summoned a crew to rescue them in the gig. All were eventually safely back on board the Channel Queen.

Some seven years later, De Putron sought medical treatment following a period of employment as third mate on the iron screw steamer Nile (1868) of London, owned by Charles M. Norwood. He was admitted to the Dreadnought suffering from venereal disease on 7 April 1873 and was discharged cured on 27 May 1873.

In the nineteenth century, syphilis and gonorrhoea (and related complications) dominated the statistics of infectious diseases among sailors in the merchant service. As part of the evidence given to an Admiralty committee on the problems of venereal disease in 1865, it was stated that between one and two thousand cases were admitted to the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on an annual basis.

Towards the end of his career, De Putron seems to have been well known in Hobart, Tasmania. He was master of the iron ship Margaret Galbraith (1868), when she brought a cargo of mainly milling machinery for the Tasmanian Timber Corporation Ltd. to the port in May 1901. This was perhaps his last engagement as master. He died of septic bronchitis in hospital in November 1903, while employed as second mate on the Julia Percy (1876), a steamer used for the mail run between Fremantle and Geraldton on the west coast of Australia.

For further reading, see Memoirs of a Victorian Master Mariner: The Autobiography of Hilary Marquand, edited by Eric B. Marquand, with an introduction by Philip Riden, Merton Priory Press Ltd., Cardiff, 1996.