Daisy Chamberlain curated a recent display of Library and Archive materials relating to the Challenger Expedition (1872–76). Here she explores the hidden stories, scientific research and record of sailors' lives held within these materials.

Beyond the Ocean's Depths

On 7 and 8 November 2023, Royal Museums Greenwich, with the support of the Challenger Society for Marine Science, UCL’s Science and Technology Studies Department, and the British Society for the History of Science, was thrilled to welcome over 100 attendees to the National Maritime Museum to consider the histories and legacies of the Challenger Expedition (1872–76).

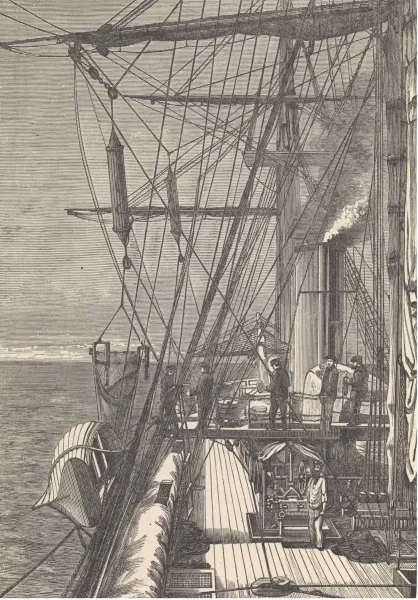

HMS Challenger departed England in 1872 on a quest to explore the world’s oceans. The voyage collected oceanographic data in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Southern Oceans, as well as the Antarctic Circle. Members of the six-person scientific staff observed currents, water temperatures and surface ocean conditions, and collected samples of ocean water, sea-floor sediments, and marine life.

In a truly interdisciplinary conference, ‘Beyond the Ocean’s Depths: Revisiting the Challenger Expedition (1872–1876)’, brought together an international group of marine scientists, artists, historians and museum curators to consider the expedition from a range of perspectives. Speakers addressed a wide range of topics, including the use of Challenger ocean sediments as a baseline for measuring climate change, the colonial legacies of nineteenth-century scientific voyages, the people whose perspectives are missing from Challenger’s otherwise well-known story, and the ways museums have put the voyage on display.

Conference attendees had the exciting opportunity to view a temporary display of original Challenger material held at Royal Museums Greenwich, which included a selection of items from the Caird Library and Archive.

The conversion of HMS Challenger

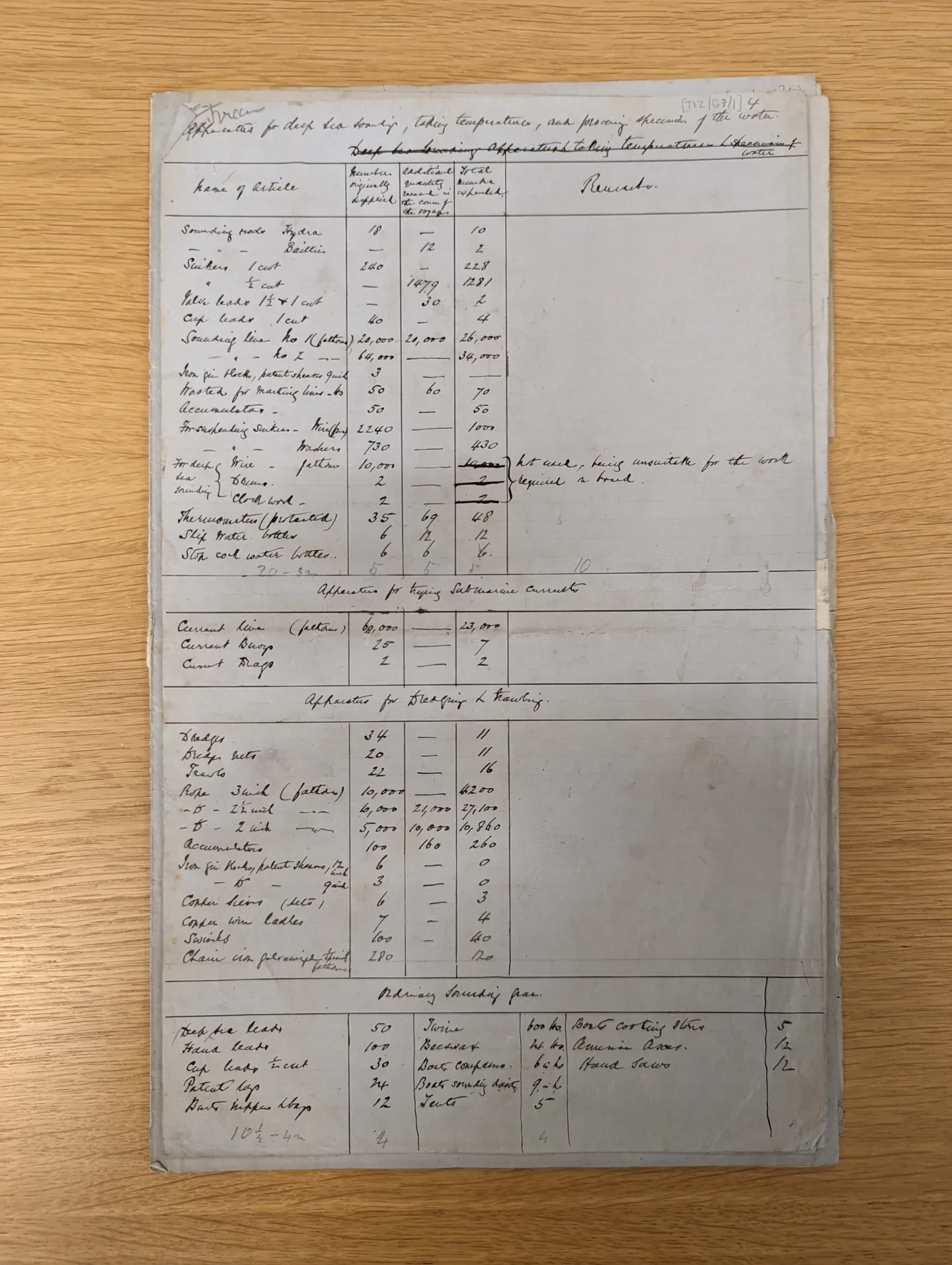

Thomas Henry Tizard began working as Navigating Officer and Assistant Surveyor onboard HMS Challenger, but was later promoted to the role of Staff Commander. Pages from Tizard’s original manuscript draft of the official Challenger narrative are held by Royal Museums Greenwich and were on display for ‘Beyond the Ocean’s Depths’ attendees. In an early excerpt, Tizard explains how HMS Challenger was selected for its size, steam engine, and ability to carry a crew and a large deal of equipment on a circumnavigation voyage (RMG ID: TIZ/67/1).

To prepare the ship for scientific work, HMS Challenger’s refit commenced at the Royal Navy’s Sheerness Dockyard in June 1872. The Admiralty estimated that repairs and modifications would require six months of planning and work.

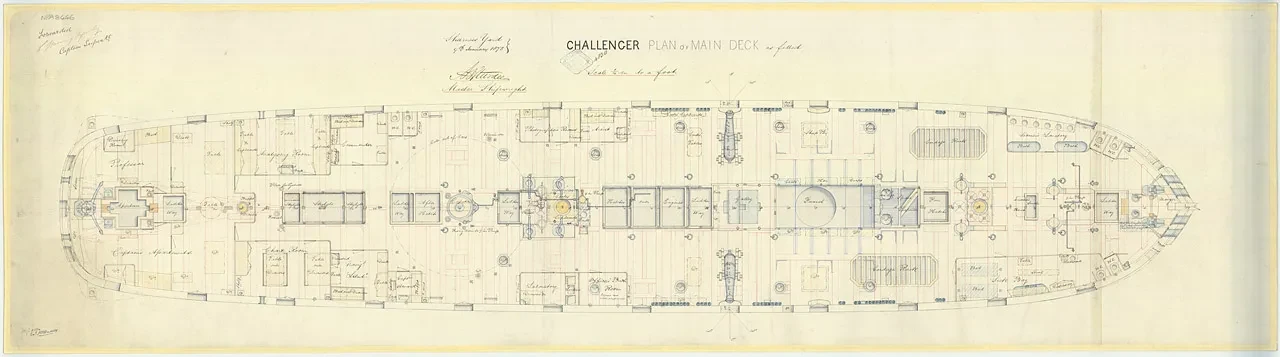

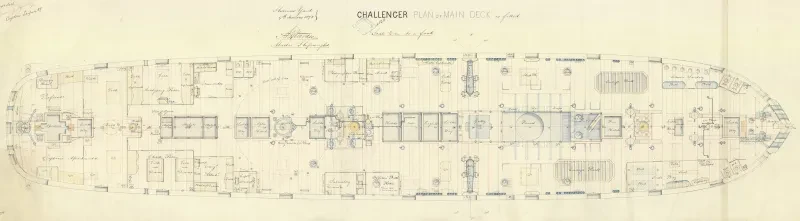

This plan for the main deck of HMS Challenger, by Alfred B. Sturdee, shows the ship as it was fitted for its oceanographic voyage (RMG ID: NPA8446). The cabins of Captain George Nares and Professor Charles Wyville Thomson, the Analysing Room, Photographers’ and Artists’ Rooms, laboratories and fittings can be seen. It was highly unusual for captains and naturalists to have cabins of equal size as can be seen here, demonstrating the importance of the expedition’s scientific work.

Setting sail, experiencing the environment

HMS Challenger set sail from Sheerness on the north Kent coast on 7 December 1827.

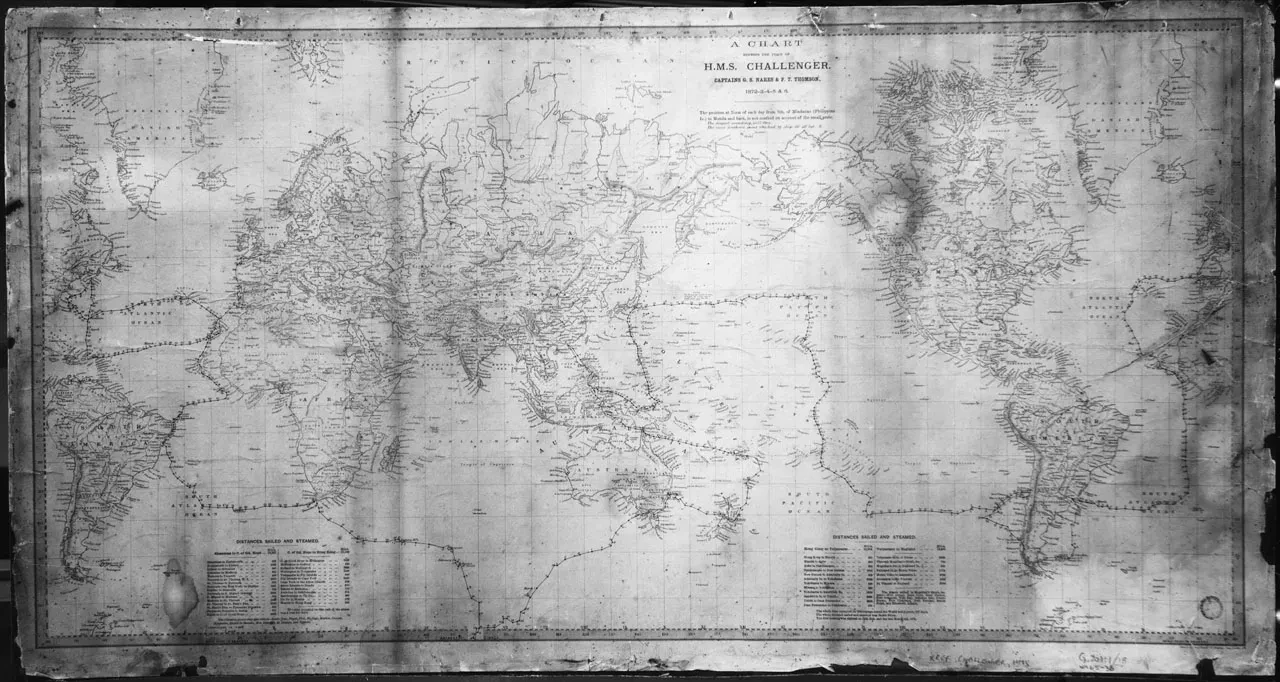

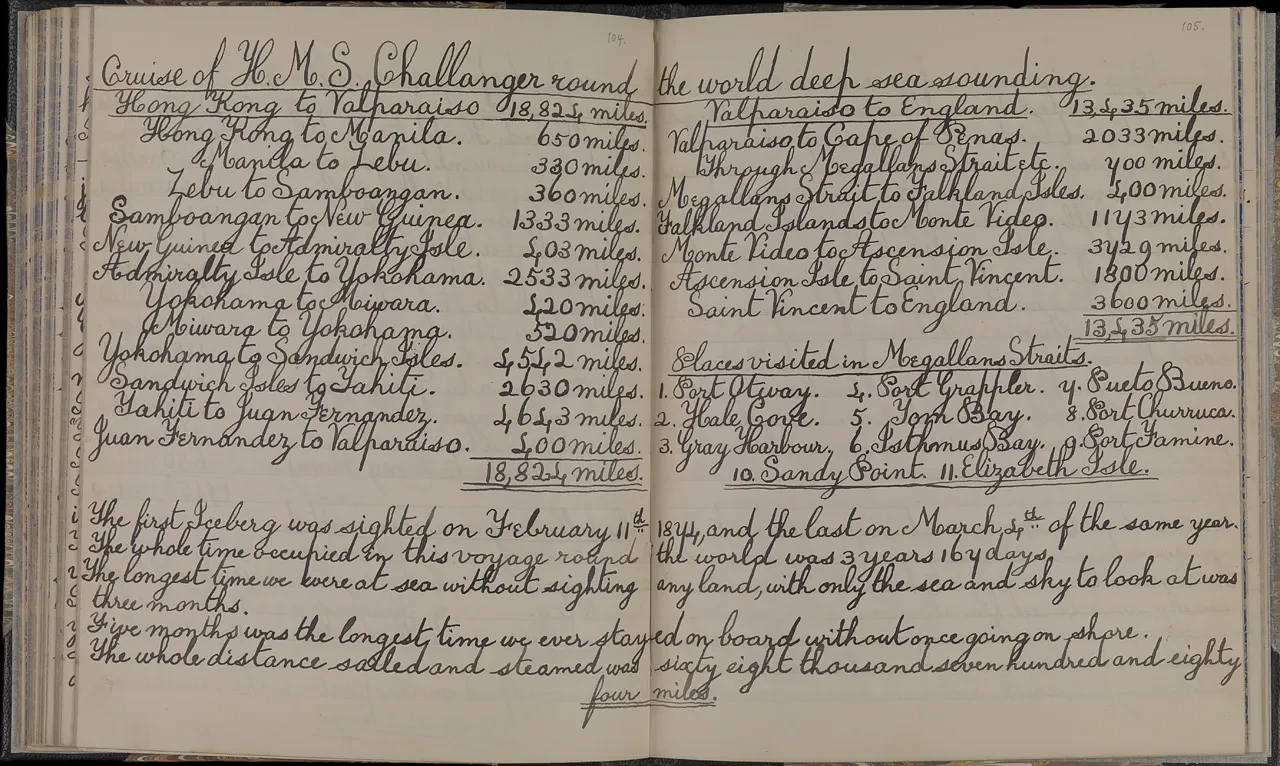

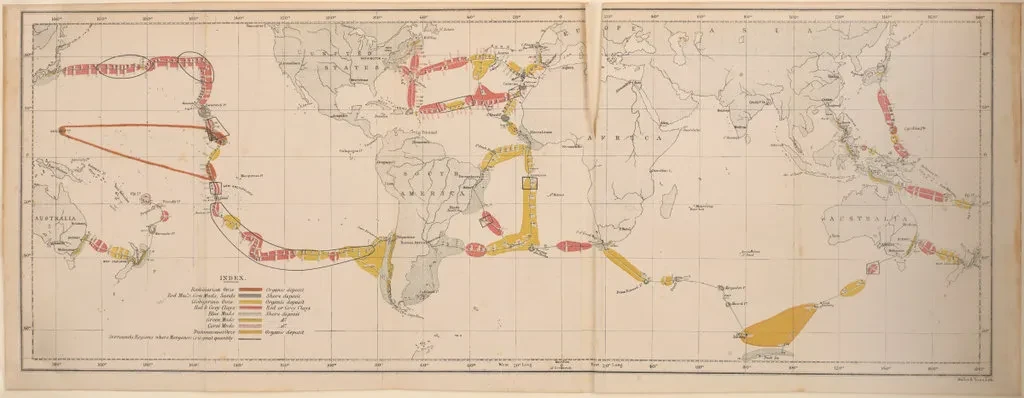

This chart (RMG ID: G201:1/18), showing the track of HMS Challenger, reveals the global scale of the voyage. After departing from Sheerness, Challenger’s circumnavigation encompassed some 68,890 nautical miles across the Pacific, Atlantic, and Southern Oceans, and it was the first steamship to cross the Antarctic Circle. Over three and a half years, the expedition carried out oceanographic experiments at 504 stations. Marking these ocean stations accurately on charts required careful and precise measurements of latitude and longitude by Challenger’s navigational officers.

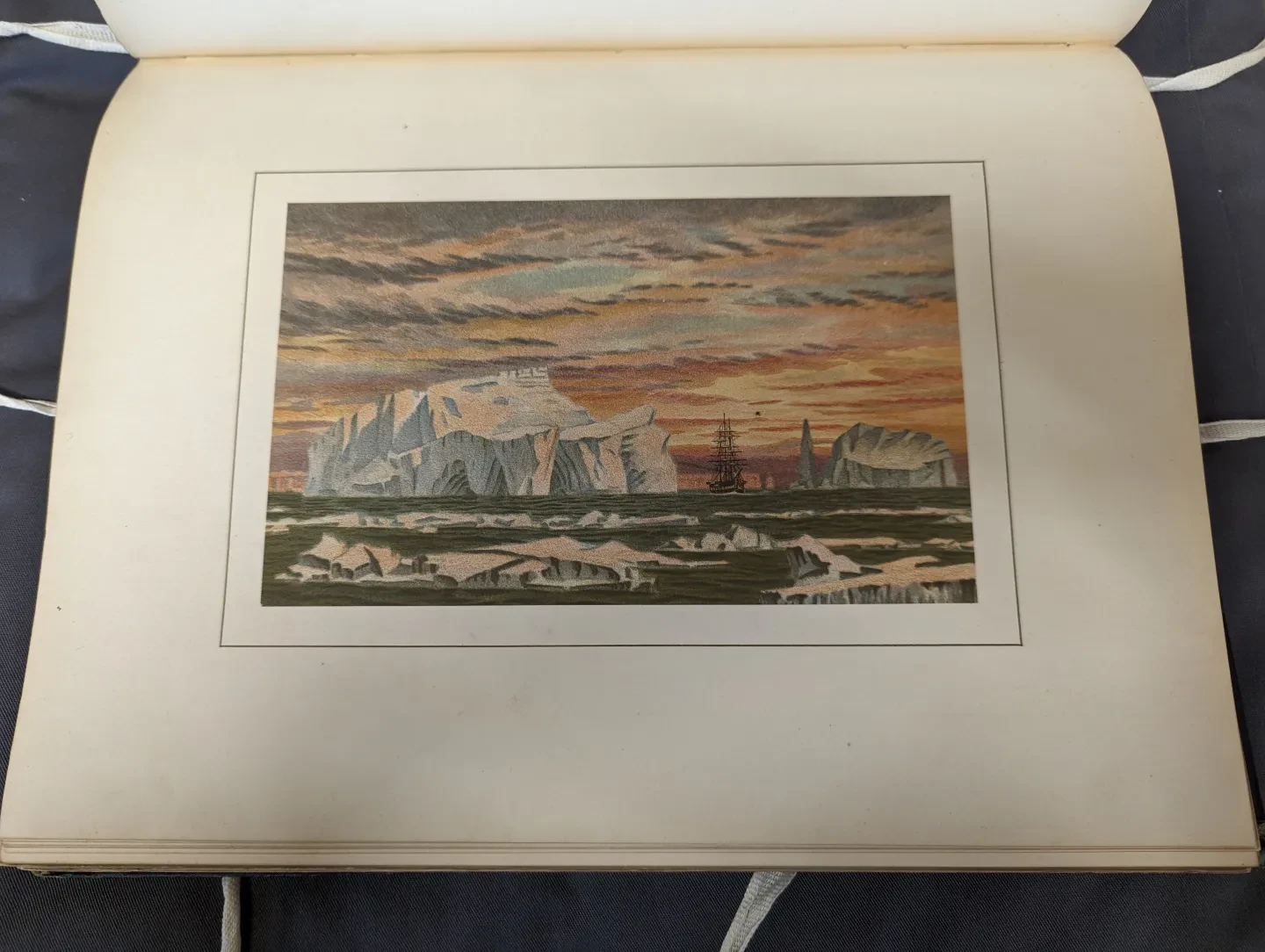

While on board the ship, members of the crew attempted, through photographs, illustrations, and words, to capture the beauty of the world around them. The crew was particularly amazed by the views of vivid aurorae and large, imposing icebergs they encountered in the Antarctic Circle.

In a letter sent from the ship, later published in At Sea with the Scientifics (RMG ID: PBP2408) Joseph Matkin describes the Aurora Australis sighted by the expedition on 4 March 1874:

On the 4th at 1am, we had a splendid display of the Aurora Australis, & turned out of my roost to see it; the flashes of light varied in colour, being white, orange, yellow & purple. It was a magnificent sight, tho’ rather chilly the way I was dressed.

The Challenger Expedition was the first voyage to capture a photographic image of an iceberg in the Southern Ocean. This photograph taken by Frederick Hodgeson in 1874 (RMG ID: ALB0175) is one of a series made from the ship.

The photographs of icebergs were slightly distorted due to the cold temperatures and the reaction with the photographic chemicals used. Photographs could also not accurately capture the deep blue hues that were better rendered in ink. John James Wild served on the Challenger Expedition as official artist and personal secretary to Charles Wyville Thomson. His illustrations, contained within his own narrative of the expedition (RMG ID: PBD4528), include vivid paintings of the icebergs observed by the Challenger crew.

Matkin’s published letters (RMG ID: PBP2408) also include a description of the icebergs in the Antarctic Circle in a message sent on 16 February 1874:

On the 14th over 30 large Icebergs were in sight from the deck, and the great ice barrier about 5 miles away looking like low-land covered with snow, & a pale misty light hanging over it. The ice-bergs were of all shapes & sizes, from a Gothic Cathedral to a Haystack, and varied from 100 to 500 feet in height, & the largest were about 4 square miles in extent. Some had spires to them like churches, others bays and harbours running into them, & many were honey combed with caverns extending through them in all directions.

[…]

We passed one on the night of the 14th, which looked something like Windsor Castle, & had a large cavern through it which showed the daylight on the other side; nearly all hands were on deck to see it, & one of the men even said, he had often paid a penny in England to see not half such a sight. At midnight it was light enough to see to read, & the sky was still scarlet in the west where the sun had gone down.

Indigenous knowledge of the ocean

The Challenger Expedition’s crew made contact with Indigenous peoples around the world in places including Fiji, Hawaiʻi and Tonga, to name a few examples in the Pacific Ocean. The display included published accounts and photograph albums, which document these Indigenous communities and the local knowledge upon which the expedition often relied.

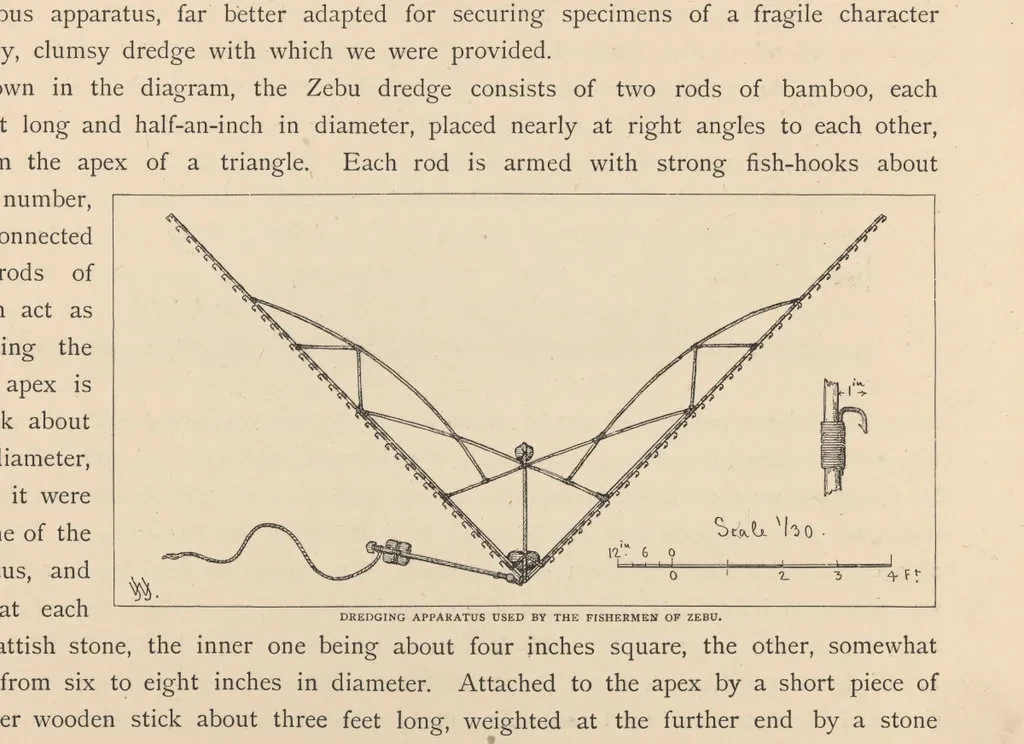

This dredging apparatus, illustrated in John James Wild’s At Anchor (RMG ID: PBD4528), was used by the fishermen of Cebu in the Philippines and adopted by the Challenger staff. When the heavy iron dredge used on HMS Challenger damaged fragile marine animals attached to the ocean floor, such as glass sponges, this lighter apparatus, made from wood, helped the crew to obtain several intact sponges from the waters around the island.

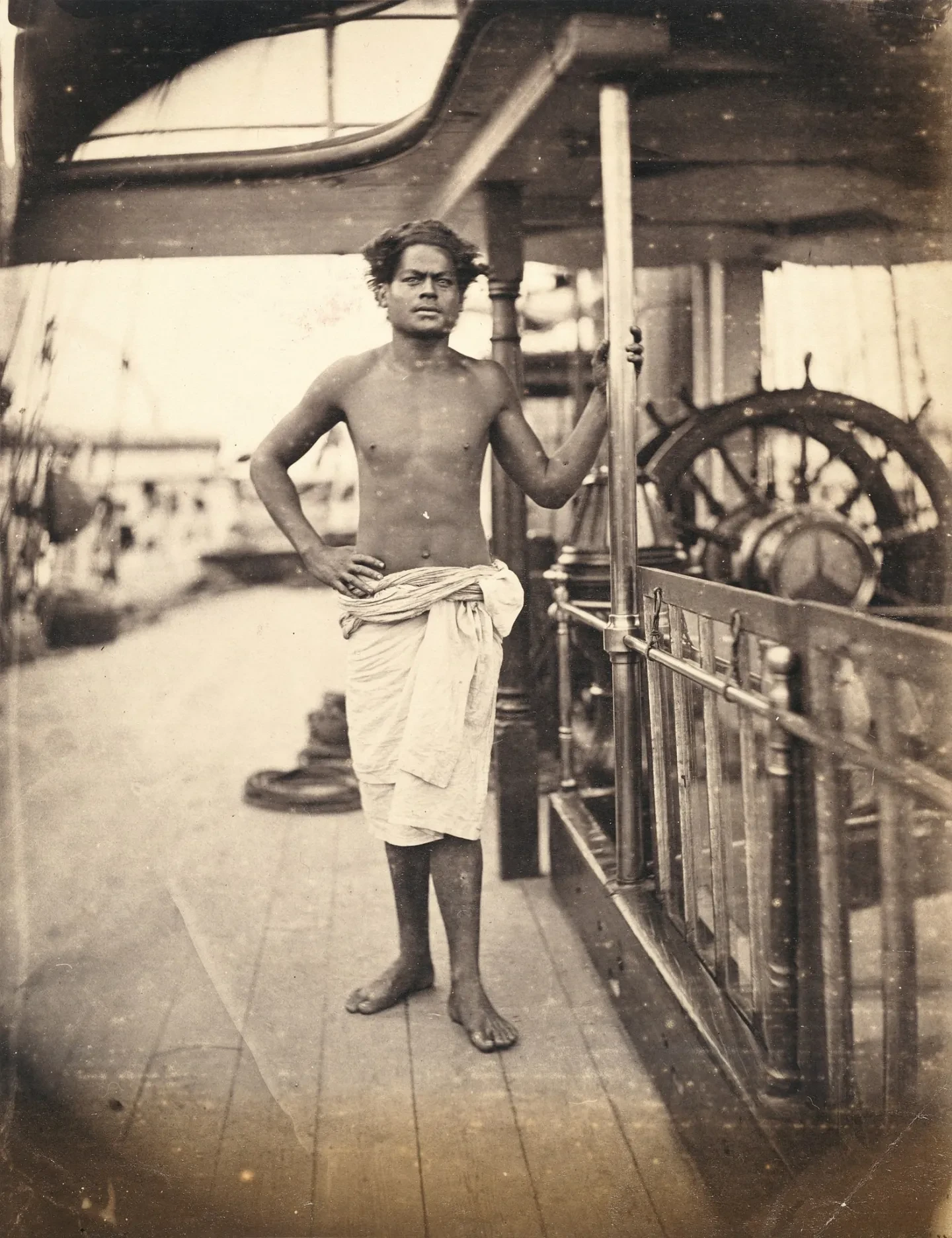

This portrait, taken by Frederick Hodgeson, shows a member of a Tongan boat’s crew (RMG ID: ALB0175). He met the Challenger crew on an English whaleboat belonging to Siaosi Tupou I, King of Tonga and helped to guide HMS Challenger through the reefs surrounding the island to a mooring near the capital city of Nukuʻalofa. Whilst this individual’s name was unfortunately not recorded, the ship’s wheel, positioned his left, highlights his navigational expertise.

Indigenous agency in the photographic encounter

Some of the naturalists on board saw the expedition as an opportunity to study and photograph the coastal communities and Indigenous peoples with whom they came into contact. Some of these photographs were composed as part of ethnographic studies and in the context of British imperialism, were used to support now debunked theories of white supremacy.

Indigenous people were not given much agency in the production of ethnographic images, but, occasionally, they did have some. In a photograph included in the display of the Tongan pilot’s boat crew, the coxswain wears a pea jacket (RMG ID: ALB0175). In his memoir of the voyage (RMG ID: PBB3958), which was also on display, the naturalist Henry Nottidge Moseley recalls asking him to take the coat off ‘in order to make the group uniform’ for the photograph. The coxswain refused, maintaining some say in the way he was depicted.

The photographic collection offers little information about the individuals it depicts, but it provides an insight, from the perspective of the white European scientists – into the communities met by the Challenger Expedition during its circumnavigation.

Hidden histories: HMS Challenger’s crew

In addition to the six-person scientific team led by Professor Charles Wyville Thomson, HMS Challenger had a ship’s company which included some 250 sailors. Little is known about these individuals, but the conference display revealed fragments of their lives and the work they carried out on board.

The conference display included the memoir of Abraham Smith (RMG ID: BGR/41). Smith devoted a large part of his memoir to his service on the Challenger Expedition, and his writing contains many valuable stories of life on board the ship.

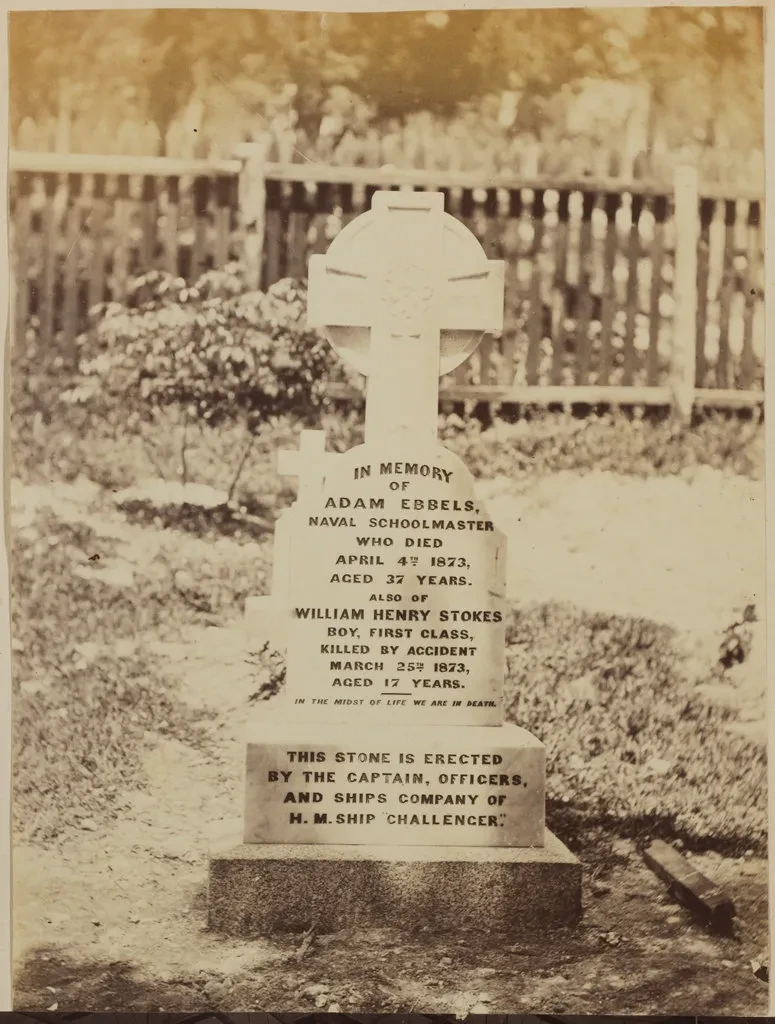

The messy work of dredging was often left to the sailors, rather than the naturalists. Hauling up materials and animals from the ocean floor was physically taxing and could often be dangerous. On 25 March 1873, a young boy named William Stokes died during a dredging accident. While in the Falkland Islands, Able Seaman Thomas Bush also fell overboard and drowned. He was later buried at Port Louis. The published letters of Joseph Matkin (RMG ID: PBP2408) include a letter from 7 April 1873 about the fate of William Stokes:

The dredge was hove overboard, and the strain on the line was so great when it reached, the bottom, that when they commenced hauling it in, it carried away an iron block that was screwed in to the Deck, and had all the strain to bear. The block as it flew up struck a sailor boy, named [William] Stokes, on the head, & dashed him to the deck with such a terrible force, that his thigh was broken, and spine dreadfully injured. He was carried to the Sick Bay and attended to by the Surgeons, but he was insensible the whole time, and only lived two hours.

The photograph albums contain an image of the memorial to William Stokes (RMG ID: ALB0174).

Challenger Expedition data

Vast amounts of oceanographic data were collected during the voyage, focusing on three main areas: the depths at which marine life existed, the composition of the ocean floor and the temperature of the ocean at various depths.

Along its route, the expedition performed 374 deep-sea soundings, took 255 observations of water temperature, successfully deployed the dredge at 111 stations and completed 129 trawls. Water samples, marine plants and animals, sea-floor deposits and rocks brought up from the deep were carefully preserved on board the ship and sent to the University of Edinburgh for study.

Original manuscript graphs and tables within the Library and Archive collection display the data collected by HMS Challenger’s scientists and provide insights into the advance of oceanography as a modern scientific discipline.

Tizard’s manuscript draft of the Challenger narrative (RMG ID: TIZ/67) includes a list of apparatus supplied for deep-sea sounding, taking temperatures and procuring specimens of the water, and a description of the methods used for obtaining water temperatures.

International collaboration: Challenger’s legacy

The final Challenger Report combined data from the Challenger Expedition with that collected on voyages made by other nations. This international collaboration greatly enhanced the charts contained within the Challenger Report.

This chart of deep-sea sediments, published in George Campbell’s Log-letters from the Challenger in 1877 (RMG ID: PBB3924) represents the ocean floor samples collected along the route of HMS Challenger.

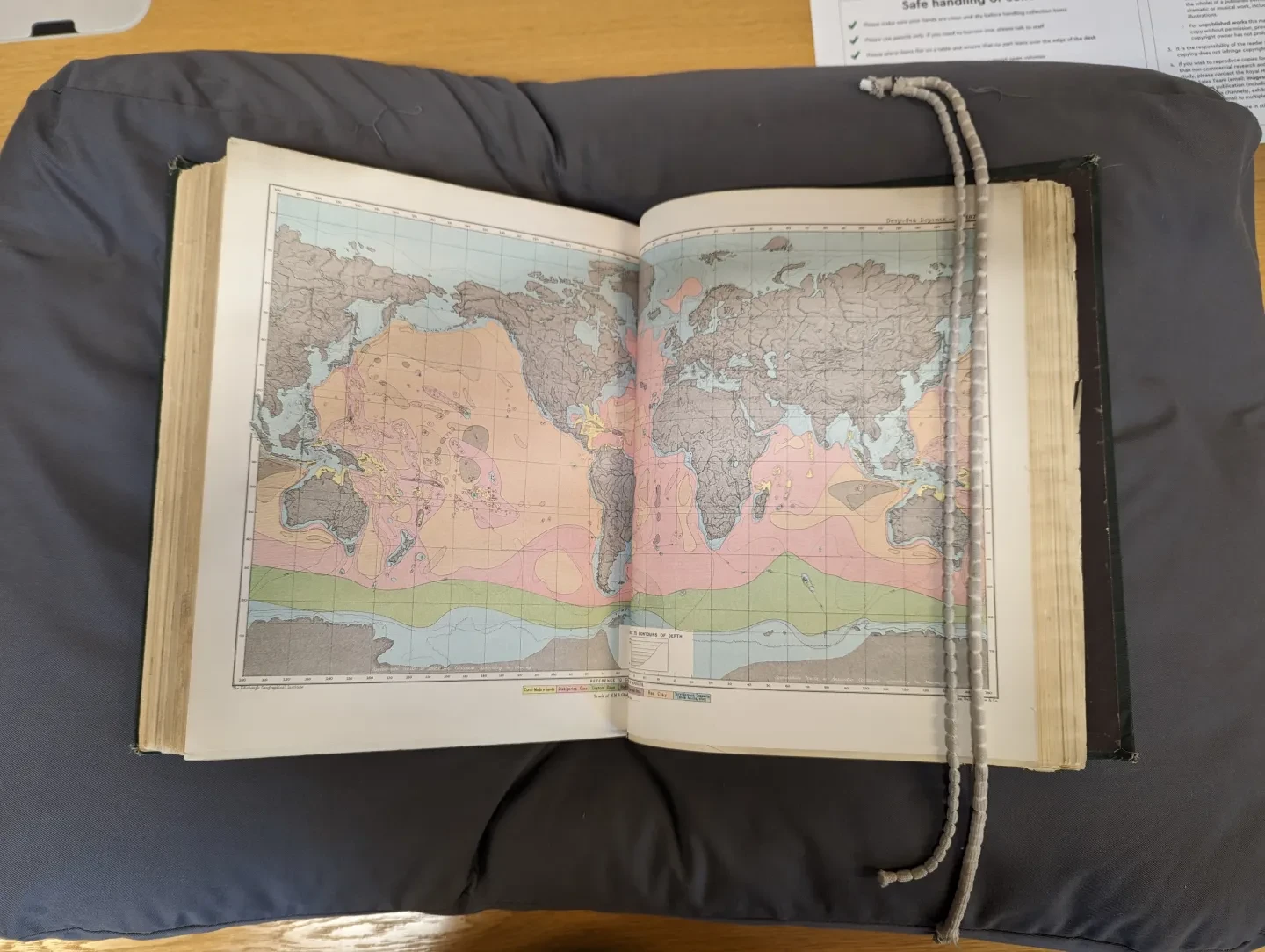

There is a striking difference between the chart found in Campbell’s publication, made from observations during Challenger’s 1872–76 voyage, and the more comprehensive chart published in the final Challenger Report in 1891, which combines the information collected by many other voyages and expeditions. This chart, visualising the global distribution of deep-sea sediments, was one of the Challenger Report’s most consequential achievements. It was published in the Report on Deep Sea Deposits, which was co-authored by John Murray and Alphonse-Françoise Renard, and is held by Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG ID: PBP7849). Visitors to the conference display had the opportunity to view these charts side-by-side and appreciate the impact that international collaboration had on the findings of the Challenger Expedition.

Key to the map of the global distribution of deep-sea sediments:

- Yellow: ‘Coral, Muds, and Sands’ (soft sediments found near coral reefs)

- Pink: ‘Globigerina Ooze’ (made up primarily of a type of plankton called Foraminifera)

- Orange: ‘Red Clay’ (clay derived from the land)

- Green: ‘Diatom Ooze’ (deposit made from skeletal remains of floating organisms)

Royal Museums Greenwich holds a wealth of material relating to the Challenger Expedition, including published primary sources, unpublished archival documents such as manuscripts, charts and maps, visual and photographic sources, and objects. It is an invaluable resource for researchers investigating the history of the voyage and the establishment of oceanography as a modern scientific discipline. The items included in the Beyond the Ocean’s Depths conference display and many more relating to the Challenger Expedition, can be found in our Challenger Expedition research guide.

More information on these topics is explored in The Challenger Expedition: Exploring the Ocean’s Depths by Erika Jones, Curator of Navigation and Oceanography at Royal Museums Greenwich.