This blog takes a look at an almost five-hundred-year-old geographical text in the Caird Library and Archive.

Sebastian Münster (1488–1552) was a former Franciscan monk, professor of Hebrew and the sacred languages at the University of Basel, humanist scholar, and author of various editions, translations, and works on cartography and geography.

His most famous work was the Cosmographia, originally published in German in 1544, which subsequently went through more than twenty different editions. The copy held in the Caird Library (PBE4055) is the expanded 1550 edition in Latin. It is generally held to be the definitive edition of the text. But why was this the most definitive and popular edition of a colossal work of geography written in Latin, a language nobody outside the Church had actually spoken for centuries?

Latin and geography’s classical sources

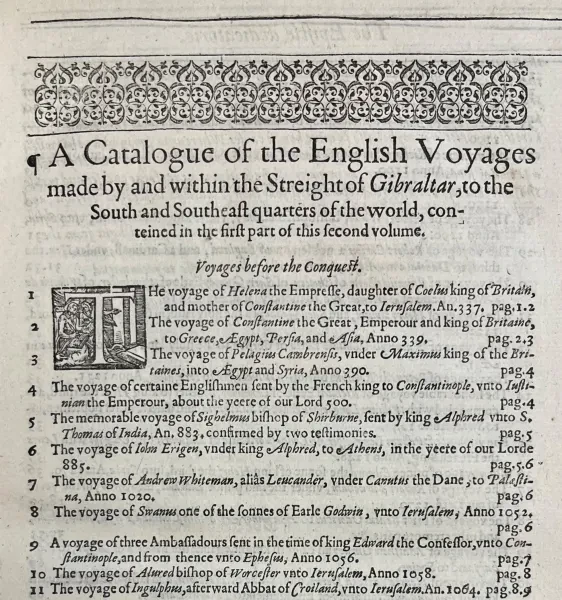

Latin and Greek were the languages of the Classical geographical texts that many mediaeval and later geographical authors took as sources. Geographical writing across the mediaeval period and beyond owed a great debt to texts concerned with the mathematics of geography – Eratosthenes, Mela, Claudius Ptolemy – as well as texts that combined geography with ethnography – Herodotus, Caesar, Strabo, Tacitus, and very often Pliny the Elder.

Latin was a dead language that had to be read to access these ancient sources, but it was also the language of the Church, which had standardised a written form of it and spread it across a large part of the Christian world. Latin’s association with antiquity and Christianity meant texts in Latin were seen as authoritative, and so it was often used as the language of diplomatic communication.

Latin also gained the status of being the ‘universal’ language of scholarship and scholarly communication, especially during the Renaissance, which involved a revival of Classical ideas and texts. For example, Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography remained influential in the Islamic world, but Greek manuscript copies were only brought from Constantinople to Western Europe and translated into the more accessible language of Latin in the very early fifteenth century. Münster translated and published a Latin edition of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography in 1540. The Caird Library has a copy of the 1552 edition (PBD7691/1-2).

Classical geographies, especially of the mathematical flavour, attempted to map the known world using observation and measurement, however flawed, rather than basing geography on Biblical knowledge and efforts to demonstrate the divine order of creation. The rediscovery or reassessment of these texts coincided with European awareness of the Americas – not mentioned in the Bible! – which forced a re-evaluation of traditional mediaeval geographic knowledge and led to an explosion in new geographical works.

Münster’s Networks

It is around this period when Münster, who had recently left the Franciscan order to take up a teaching post at the University of Basel, began his own geographical works. Münster had previously helped to edit and publish the geographical works of his old mentor, Gregor Reisch, and then his own aforementioned edition of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography.

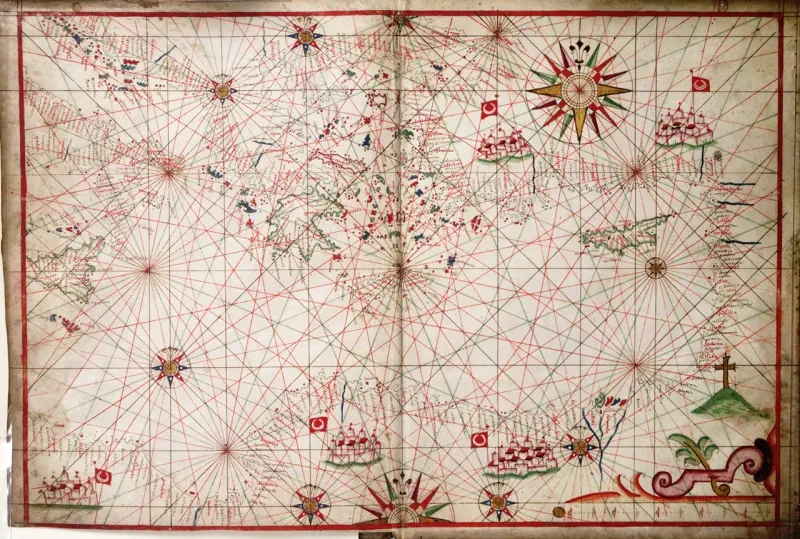

But when Münster began the enormous task of putting together the Cosmographia, although he conducted a great deal of his own research, his travels never took him outside of his native Germany. He thus relied on his extensive network of fellow scholars across Europe, whom he was able to communicate with through their shared language of Latin.

The text of some of this communication can be found in R.W. Karrow’s Mapmakers of the sixteenth century and their maps: bio-bibliographies of the cartographers of Abraham Ortelius 1570, available in the Caird Library on open access (PBP2948).

The extensiveness of Münster’s network, which he asked to provide him with notes, geographic descriptions, and loans of existing texts (often in Latin), meant that the expanded Latin edition of the Cosmographia is even able to provide a brief description of Greenwich, which I have translated below:

Alterum [amnem] appellatur Tamesis, ad cuius ripam collocatur regia Angliae, nempe Londinum, quod olim Trinovantum fuit vocatum. Tempore nostro est insigne emporium & mercatus in eadem urbe, possuntque maiores naves per Tamesim illuc deduci. [...] Porro tribus millibus passuum a Londino versus orientem, etiam iuxta fluvium Tamesin, est Grevenuvich, regum Angliae commune receptaculum. Illic naves ascendunt Londinum usque, quae ab equis non trahuntur, sed vel venti impulsu vel maris fluxu & refluxu. In Tamesi fluvio tria vel quatuor cygnoru millia domestica dicuntur inveniri.

Sebastian Münster, Cosmographia

Another river is called the Thames, and on its bank is found the capital city of England, namely London, which was once known as Trinovantum. In our times there is an important market and centre of trade in that city, and larger ships can be launched into the Thames there. [...] Three miles further east from London, and very close to the River Thames, is Greenwich, the common dockyard of the English kings. Ships sail from there up to London, not pulled by horses, but pushed either by their sails or by the ebb and flood of the tide. It is said that there are three or four thousand domesticated swans in the River Thames.

Author’s translation

Parts of this description are in fact taken word for word from the Latin text of Scottish author John Major’s 1521 work Historia Maioris Britanniae (History of Great Britain). Münster’s use of this information was enabled by it being written in Latin, making it more accessible and thus more attractive to his scholarly connections, who could have shared this paragraph or the entire text with him.

Münster’s Latin descriptions of Britain and Germany in the Cosmographia are also significant in how they differ from Classical authors’ descriptions of the same regions. Britain and Germany were both famously and uncharitably described by the Roman authors Caesar and Tacitus, who depicted their inhabitants as barbarians to be conquered by the growing Roman empire.

German humanist scholars, including Münster, began the long process of re-evaluating and overwriting these enduring negative descriptions using their own experience and research. They composed many of their updated descriptions in Latin due to its authoritativeness as the universal language of scholarship, while understanding that antiquity did not mean Latin texts were always authoritative.

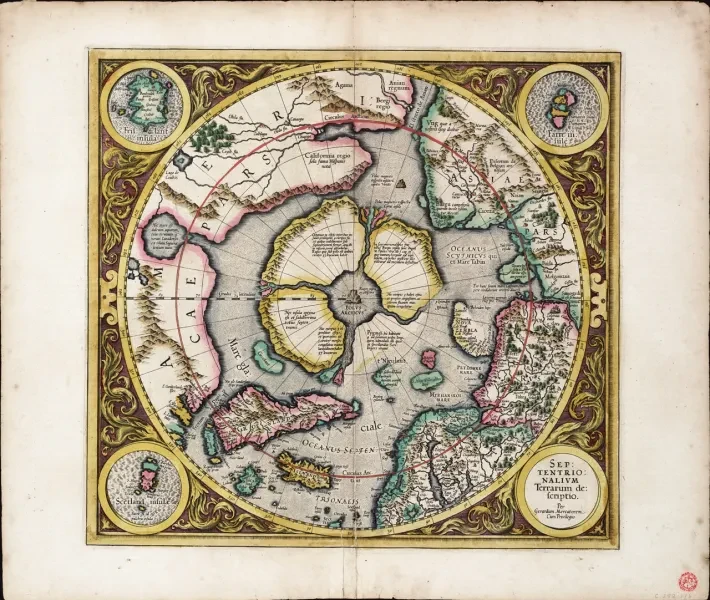

Münster’s Monsters

However, while Münster and his fellow humanist geographers were willing to reassess their Classical sources for the areas of Europe they knew and inhabited, they were less willing to extend this to the edges of their known world. This is glaringly obvious from Münster’s descriptions (with accompanying woodcut illustration) of fantastical creatures such as headless men with faces on their torsos, people with dogs’ heads or single giant feet, and cyclopes. Münster places these fictitious creatures both on the North of the Ganges in India and in the interior of Africa, citing various ancient authors.

Perhaps if he and his contemporaries had not been as invested in emphasising Europe as centre of civilisation and scholarship they would not have reproduced the Classical and mediaeval traditions that defined this civilisation against a barbarian ‘other’ so uncritically. At the same time, they (and the printing industry) also benefited from sales of books, which were more attractive if they included spectacular illustrations of fabulous creatures...

Conclusion

Münster wrote the Cosmographia during a period of immense geographic innovation. The choice of language for the definitive edition mirrors its sources and process of composition, and reflects a curiously transitional period of simultaneously relying on and questioning the authority of the received geographic tradition.

Despite its intention as a ‘universal’ geography written in a ‘universal’ language, its contents (centring Europe and exoticising its peripheries) and language (Latin, a language only ‘universal’ to a European elite) show clear assumptions about just whose universe Münster and his contemporaries thought it was.

The Cosmographia would be one of the most popular books of the sixteenth century, and new editions continued to be published for over a century.

Further reading

Claudius Ptolemy. Geographiae Claudii Ptolemaei Alexandrini, philosophi ac mathematici praestantissimi, libri VIII. Basel: Henricus Petrus, 1552. PBD7691/1-2.

Robert W. Karrow. Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and Their Maps: Biobibliographies of the Cartographers of Abraham Ortelius, 1570. Chicago: Speculum Orbis Press, 1993. PBP2948.

Matthew McLean. The Cosmographia of Sebastian Münster: Describing the World in the Reformation. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2007.