HMS Challenger was sent around the world in 1872, with instructions to investigate not only the ocean’s depths and temperature but also the flora, fauna and human inhabitants of the places at which it anchored or made port.

Photographs brought back from the expedition show some of the individuals Challenger encountered. Individuals in these photographs are rarely identified by name, with their original compilers opting instead to caption images with generalised – and often derogatory – terms for peoples they encountered.

My research, as part of my Caird Fellowship with Royal Museums Greenwich, has revealed much more information about these individuals in the first ever systematic comparison of Challenger materials around the UK.

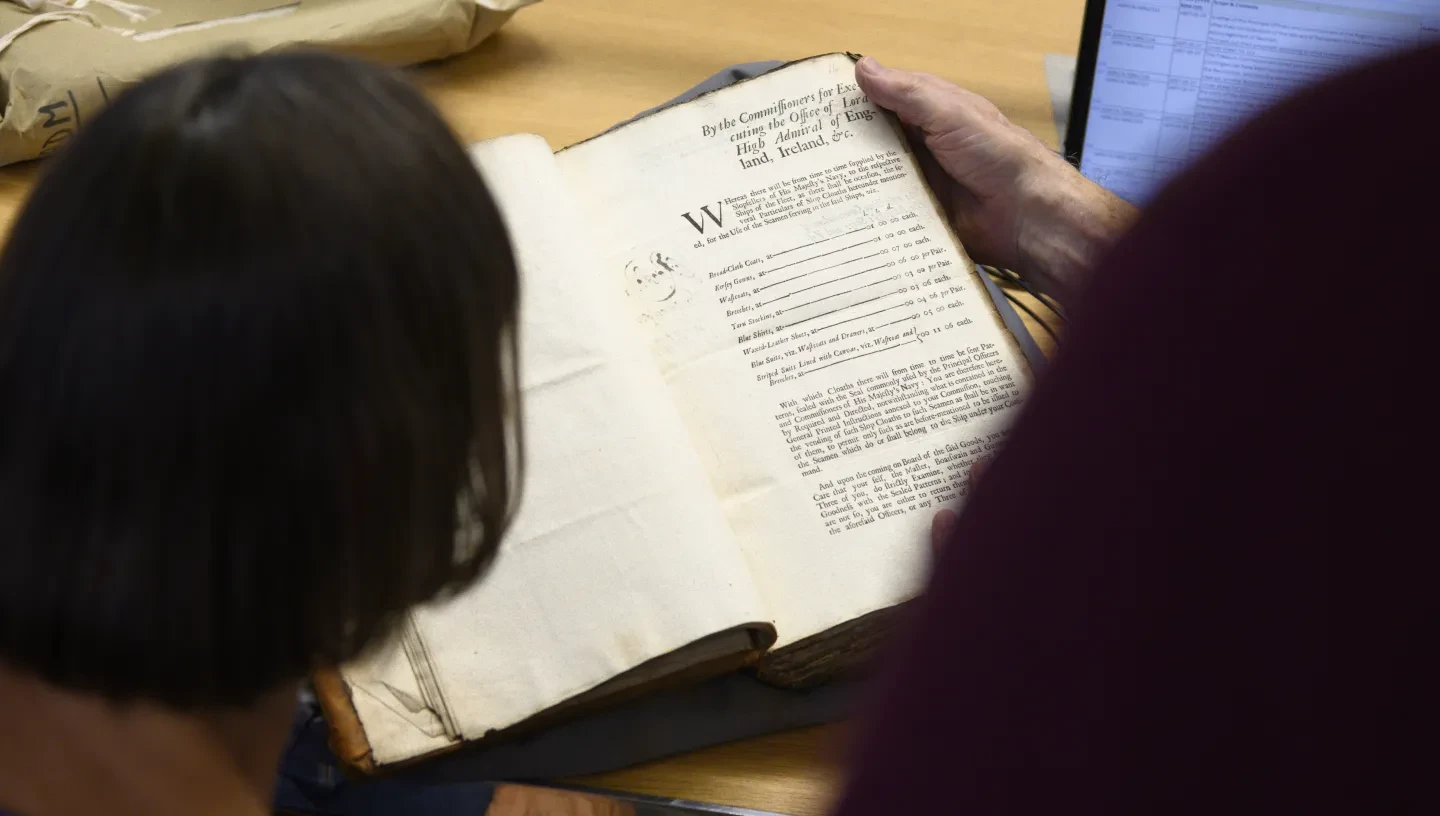

I have scoured diaries, photo albums, image captions, personal correspondence, official reports, naval documents and other notebooks and records to find and connect tiny pieces of information that might tell us something about the various individuals depicted within the HMS Challenger photograph albums at the National Maritime Museum.

This research will allow us to restore a little of the personhood to these individuals in our catalogues and records – personhood that has been forcibly removed from these images by colonial attitudes and historic discrimination.

Here are some of their stories.

Photography on board HMS Challenger

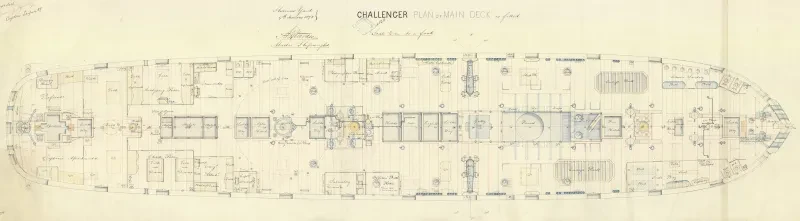

HMS Challenger was refitted in order to be able to accommodate the preparation of specimens from both the sea and the land, with space for five civilian scientific staff. However, it wasn't just the ship that was changed to support the expedition's scientific mission: the roles of the crew on board were adapted too.

The ship included both a sketch artist (doubling as a secretary) and an official photographer. Their images contributed to the scientific findings of the voyage, from some of the very earliest photographs of icebergs to the anthropological investigation of peoples and places that Challenger encountered.

The post of photographer was filled by three different people over the course of the expedition.

Caleb Newbold (a Royal Engineer photographer) started off with the voyage, but absconded from the ship in Cape Town in December 1873 after a particularly long stint of six weeks at sea with no landfall.

Frederick Hodgeson, a port photographer and private individual, then joined the crew, again deciding to leave in Hong Kong in December 1874 after the ship’s longest continuous period at sea (nine weeks).

The final photographer was Jesse Lay, a member of the Royal Navy adept in photography, who saw the voyage through to its end in Sheerness in May 1876.

The National Maritime Museum holds four albums of photographs from Challenger’s voyage. Three of these albums were collated by Assistant Paymaster John Hynes, with the fourth prepared by Navigating Lieutenant Thomas Henry Tizard, both of whom were able to purchase copies of the images produced by the expedition photographer, developed in his on-board darkroom.

These albums also include other images, purchased as souvenirs at various ports, and appear to have been put together as a way to personally document the journey, largely depicting people and places.

The forgotten naturalists: scientific expertise on board

When listing the scientific staff of HMS Challenger, most accounts will include five individuals: Charles Wyville Thomson (director of the civilian scientific staff), Henry Nottidge Moseley (naturalist/botanist), John Young Buchanan (chemist), Rudolph von Willemoes-Suhm (naturalist) and John Murray (naturalist).

More generous lists understand the importance of photography and specimen sketches to scientific publication and might also include John James Wild (artist) and the photographer among the scientists.

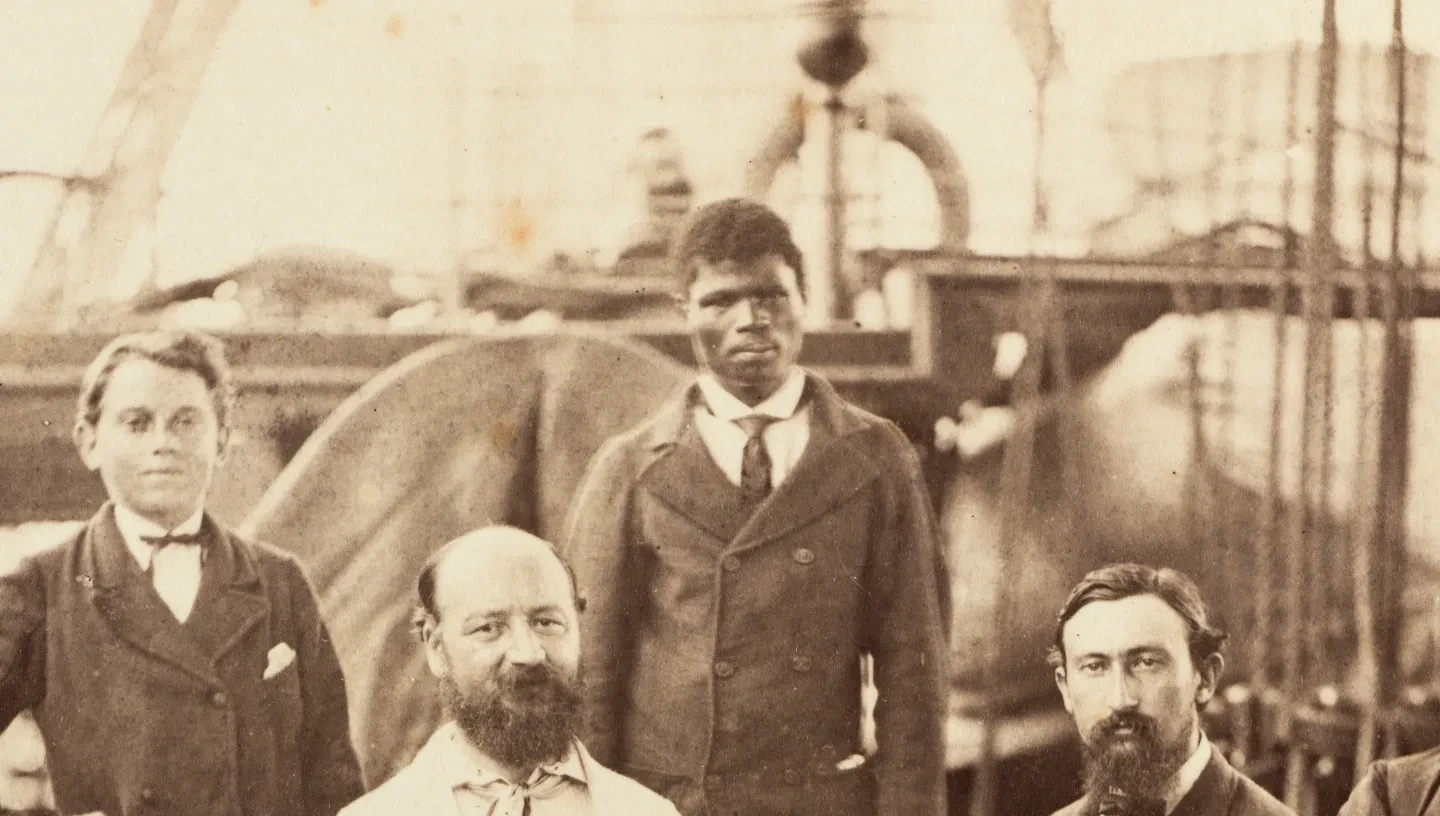

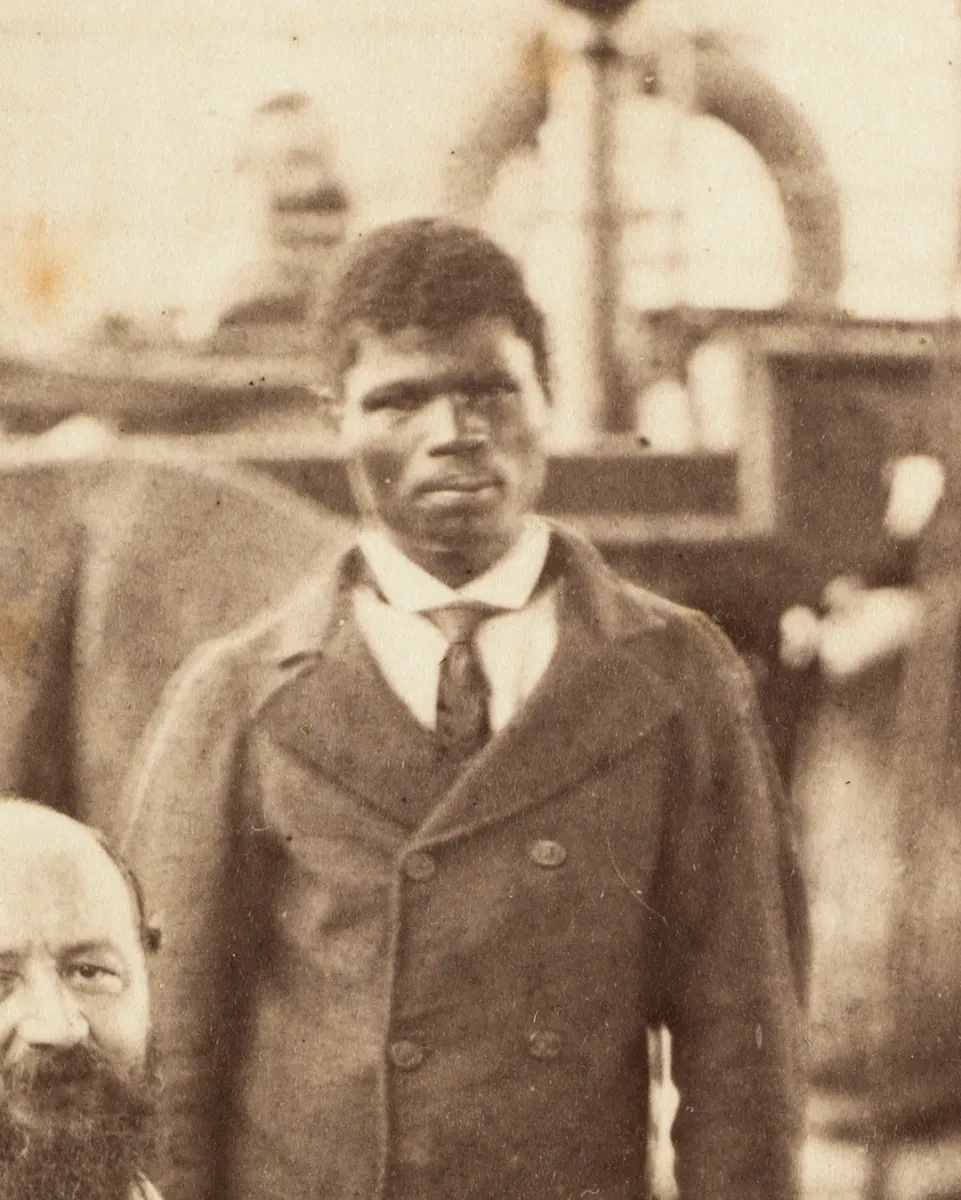

However, this team of seven is only just beginning to be expanded to include Frederick Pearcey or William Pemba, both of whom acted as laboratory assistants on board.

Of the two, it is more surprising that Pearcey has not traditionally been included, as he went on to work in the Challenger Office in Edinburgh, arranging the publication of the Challenger scientific reports with Wyville Thomson and Murray. He is also named in almost every caption attached to various reproductions of the above image of the Challenger’s scientific staff (the only image from the voyage of either man), which does not feature Wyville Thomson or, for obvious reasons, the photographer.

Pemba, on the other hand, is named in only one caption of this image – in the album of Henry Moseley, held at the University of Oxford* – with even officially framed copies referring to him simply by derogatory and/or hierarchical terms. The parrot, Robert, is named more frequently.

This exclusion from captions, coupled with little-to-no mention of Pemba in journals and published sources, has led many to ignore him as a member of the scientific staff. Conflicting spellings of his name, both by Moseley and subsequent mis-transcriptions of Moseley’s image caption (Peniber and Pembre), have made Pemba especially difficult to trace.

This exclusion in the contemporary record was likely fuelled by views on race and racial hierarchy in the period – views we would find abhorrent today – but Pemba’s presence here shows that the scientific team was more diverse than historians have previously believed. Sharing Pemba’s story is one of the ways we can continue to celebrate Black histories.

I uncovered Pemba’s naval record at the National Archives – a document previously unknown to Challenger scholars and found as a result of a single number entered underneath just one entry of Pemba’s name in the ship’s quarterly ledgers.

This record reveals that William Pemba (rating no. 85356) joined HMS Challenger at the Cape of Good Hope in December 1873. Although officially employed as a member of ‘class 3 domestic staff’, Pemba’s profession is listed as ‘Naturalist’, revealing the true role he played on board and explaining his position within the sole photograph of the scientific staff. He was one of three Challenger men we have, so far, seen described as a ‘man of colour’ in their official service records.

Pemba unfortunately fell ill and was discharged to a naval hospital in Hong Kong in December 1874. He died just a week later, either of consumption or another wasting disease, and was then almost lost to the history of Challenger.

Although lasting just under a year, Pemba’s time on board Challenger coincided with the ship’s research in the South Pacific; a region specifically identified in Challenger’s instructions as an area of special interest for naturalist work. Pemba is likely, therefore, to have made significant contributions during his time as a member of Challenger’s scientific staff.

Colonial intermediaries and expert local knowledge

Challenger’s crew also received assistance in the conduct of its scientific mission from local dignitaries and other figures who acted as intermediaries or facilitators.

Some would arrange for guides and animals to carry research equipment; others acted as both official and non-official translators. In Dr Erika Jones’ book Exploring the Ocean’s Depths you can read, for example, about the fishermen in Cebu whose expert knowledge made possible the collection of Euplectella (a type of glass sponge) specimens for Challenger’s scientists.

We might assume that the names of dignitaries and official staff would be recorded more thoroughly than others, and in some cases we would be correct. However, there are still a number of notable omissions in Challenger albums, and even in the official catalogue of photographs (later made available for public purchase), which show how much more work is to be done in uncovering the identities of those pictured.

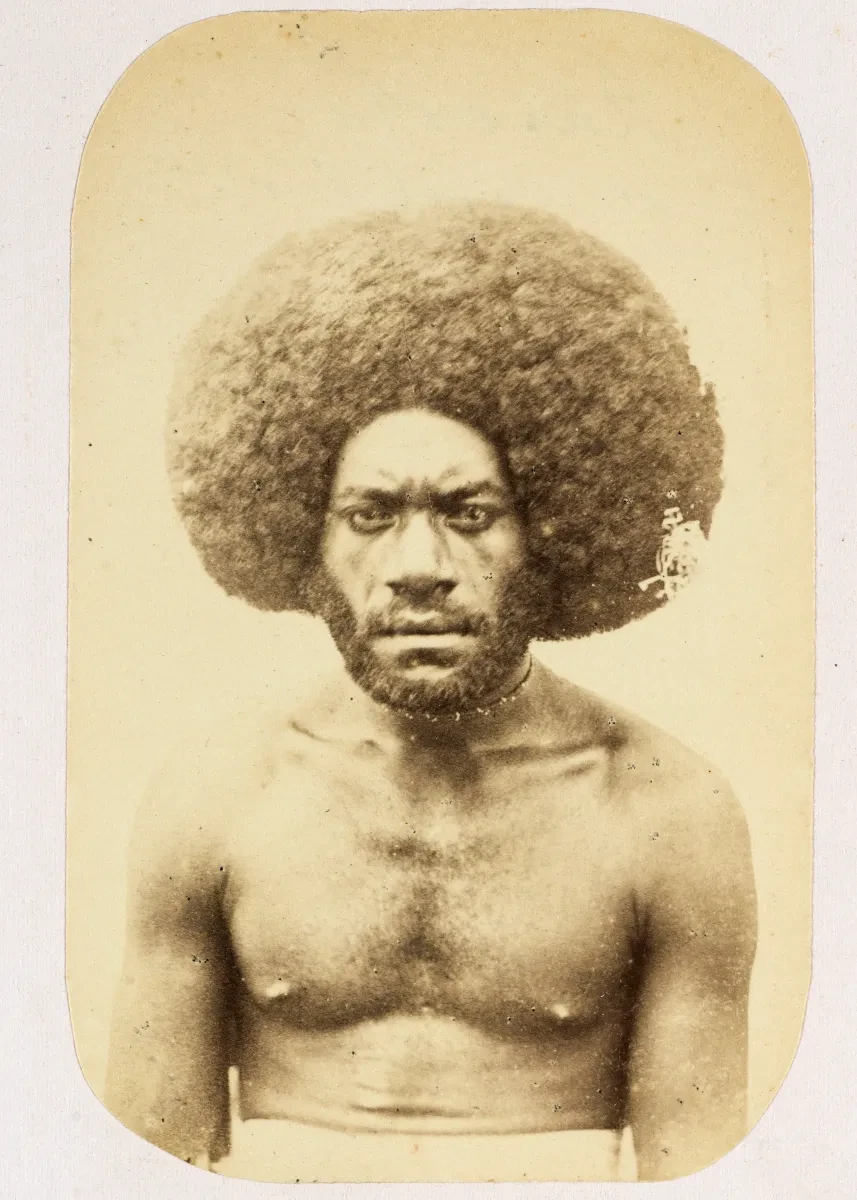

One image (pictured) from Viti Levu (Fiji), described by John Hynes as ‘Kaicolo or Devil Man’, was originally believed to be unique to the National Maritime Museum Challenger albums. When I investigated archives at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford however, I found a second copy of this image tucked inconspicuously between the pages of a letter from naturalist Henry Moseley to his mentor George Rolleston, Professor at the University of Oxford.

This duplicate image was annotated on the reverse, revealing that this man was in fact the Tui Namosi or ‘King of one of the largest mountain tribes, Viti Levu, Fiji’. This discovery corresponded with information I had uncovered when investigating one of the port photographers named in the various albums, from whom Challenger officers purchased additional photographs.

I was able to learn that mountain men/mountaineers (Kai Colo) traditionally wore large ulamate wigs of human hair, seen worn here, and that the Chief of the Namosi Province (Tui Namosi) at the time of Challenger’s stay at Viti Levu was a man named Ratu Matanitobua.

Some of Challenger’s officers and crew, including Moseley and presumably Hynes, went on an excursion towards the mountain of Viti Levu. It is likely that these two pictures were therefore acquired as cartes de visite – keepsake portraits given to those visiting influential households – and were perhaps confused by Hynes with the inmates of a prison settlement described as ‘devil men’, encountered by Moseley and his companions in the mountains of Ovalau.

Kings and chiefs in Fiji facilitated Challenger scientists’ observations of local dance and culture, as well as trade with their communities through which Challenger’s ethnographic collections were built. Historic British attitudes towards Pacific Islanders and their culture has obscured or even demonised individuals like the Tui Namosi of Viti Levu, with these perceptions left unchallenged by historians of eras past. This case shows that continuing research into what appears to be quite a well-known historical expedition can continue to bear significant results.

The challenges of the Challenger albums

Conflicting captions can obscure the identity of individuals who aided the Challenger Expedition and make difficult work for researchers looking to uncover their true identity.

The official catalogue of Challenger images (produced after the voyage) for example records an image of Nishi Bayeashi – the ship’s Japanese interpreter – with what may be his family, as simply ‘Group of Japanese’. In the National Maritime Museum collection this same image is captioned ‘Samurai or Japanese of the Upper Class’. In the UK Hydrographic Office collection it is described as ‘The High Priest of Kobé & family’, and finally in Henry Moseley’s album at Oxford the image is referred to simply as ‘Group of Middle Class Japanese’.

It was only in W.B. Carpenter’s collection at the Natural History Museum that the image caption revealed the identity of Bayeashi (spelt there Baiyashi/Baiqashi) as the ship’s interpreter in Japan. This identity was confirmed when I found, scribbled into the margins of correspondence between Captain Thomson and the Admiralty held at the UK Hydrographic Office, a note that the ship employed Nishi Bayeashi as interpreter from 11 May to 15 June 1875.

People as subjects: navigating difficult histories in the archive

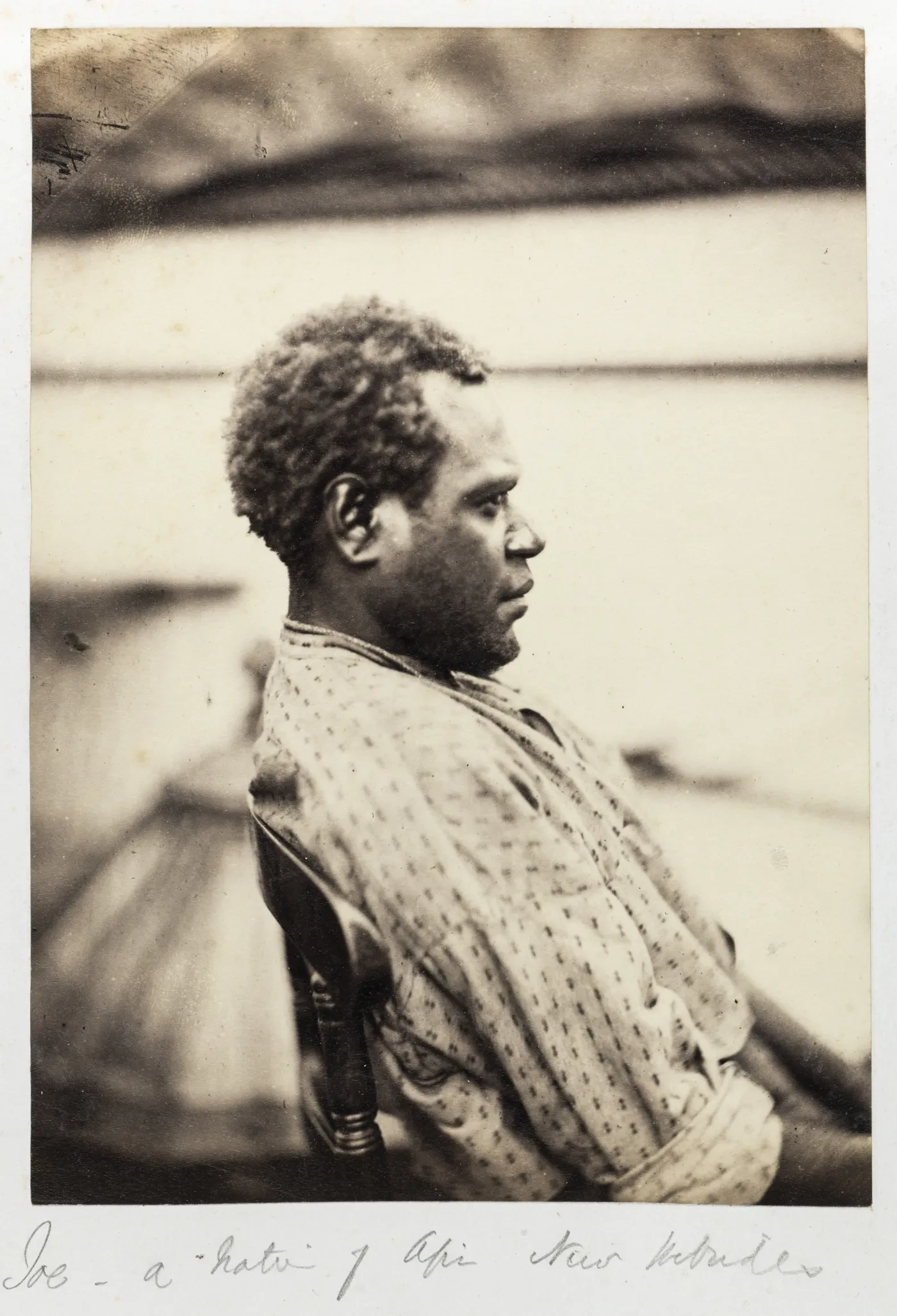

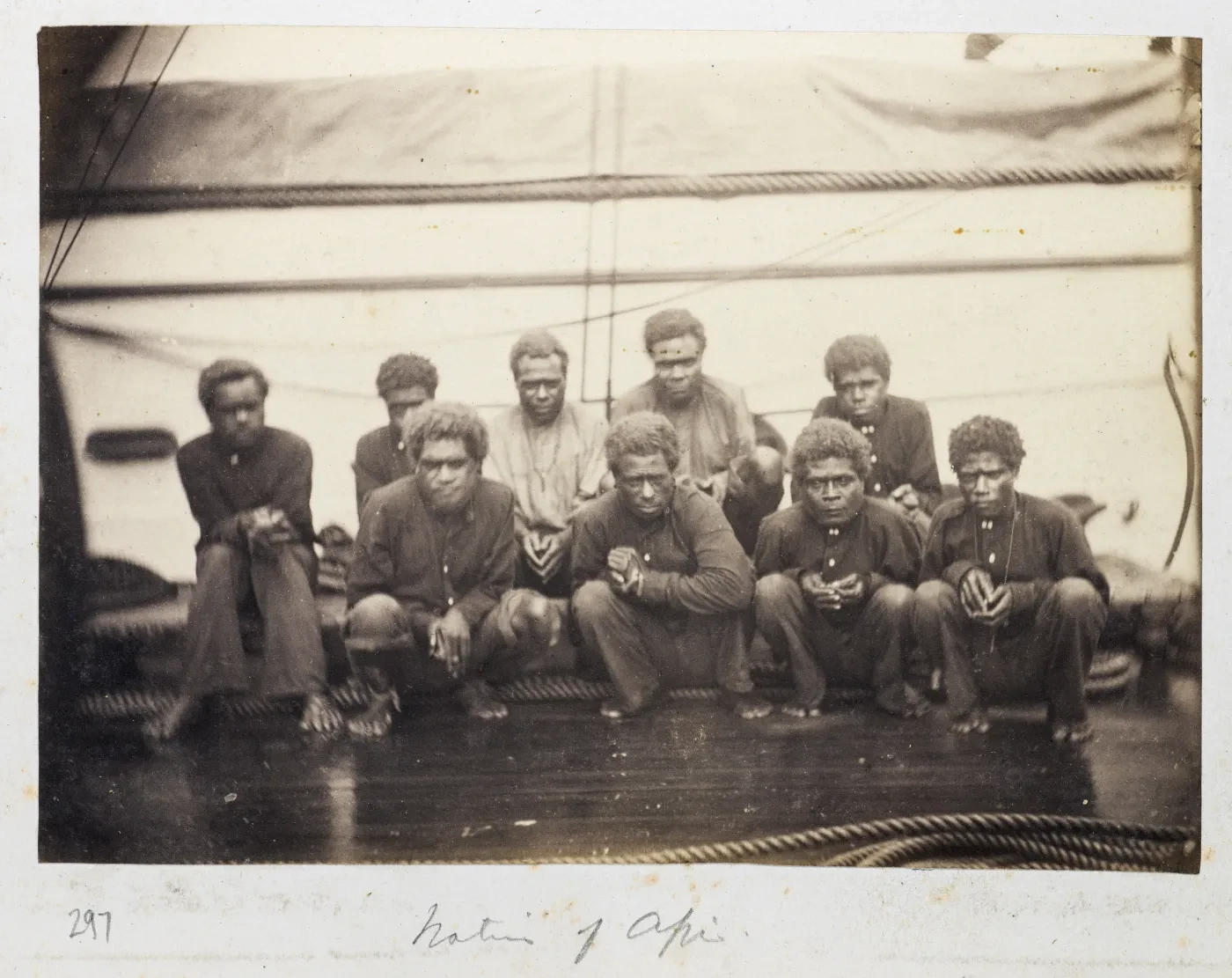

In the case of 'Toby', a man from the island of Api (Banda Islands, Indonesia) who travelled on board Challenger with some of his compatriots for 17 days in August 1874, we can see that the role of all individuals encountered by Challenger was not always clear-cut.

I found in diaries at the University of Oxford and the Natural History Museum that Toby – the only named individual of this group of Api Islanders – spoke English with the crew and informed them about safe places to land at Api. Toby was therefore a possessor of local knowledge, who negotiated Challenger’s arrival and safe passage at Api. However, his portrait in the official photographic record of the voyage hints at a history in which populations encountered by white travellers were dehumanised and reduced to objects of study.

Taken from the side, this image stands in stark contrast with the group shot of Api Islanders. Although side profile images were common in individual portraiture in the 19th century, they were also used in anthropological works on racial differences to demonstrate supposed racialised variations in head shape. Both anthropological and portrait images were taken by the Challenger photographers. However, none of the other individual portraits were taken in this side profile format and, as such, this image of Toby fits much more clearly within the anthropological group.

The anthropological study of peoples through the lens of white superiority formed a key part of the ship’s work on land during the voyage, particularly in the South Pacific and Asia. The scientific staff took and collected images, and in a number of cases bodily measurements, of individuals. They also removed without permission and unevenly traded with locals to obtain ancestral remains for study back in the UK**. Indeed, these ancestral skeletons formed the basis of two of Challenger’s 90 reports (published in 50 volumes).

In working with archives of these kinds of images, there are points at which we need to ask ourselves whether re-showing certain images gives agency to those depicted or repeats the colonial gaze. I have used this image of Toby here because we have been able to recover his name and some of his story, giving him back some of his personhood. However, in many cases this has not been possible. In these cases, the National Maritime Museum is continuing to consult with the Tangata Moana Advisory Board about the cataloguing and storage of these images, as well as discussing whether future display or digitisation is appropriate.

Dr Rebecca Martin is a Caird Fellow at Royal Museums Greenwich. Find out more about her work here.

*Materials at the University of Oxford have not yet been catalogued digitally. Contact special collections at the Bodleian library to view Moseley’s photographs, which form part of the zoology collection, and the Oxford Museum of Natural History to view the letters to George Rolleston.

**Ancestral remains removed from Pacifica and Oceanic communities during the course of the 1872-76 Challenger Expedition were repatriated by the University of Edinburgh’s Anatomical Museum in the 1990s.

Learn more about the Challenger Expedition