Throughout history there have been people willing to rob others transporting goods by water.

These people, known as pirates, have been around for thousands of years – and they still operate today.

So why do some historians talk about a 'golden age' of piracy? When exactly was this age, and was it really such a 'golden' time for scoundrels of the high seas?

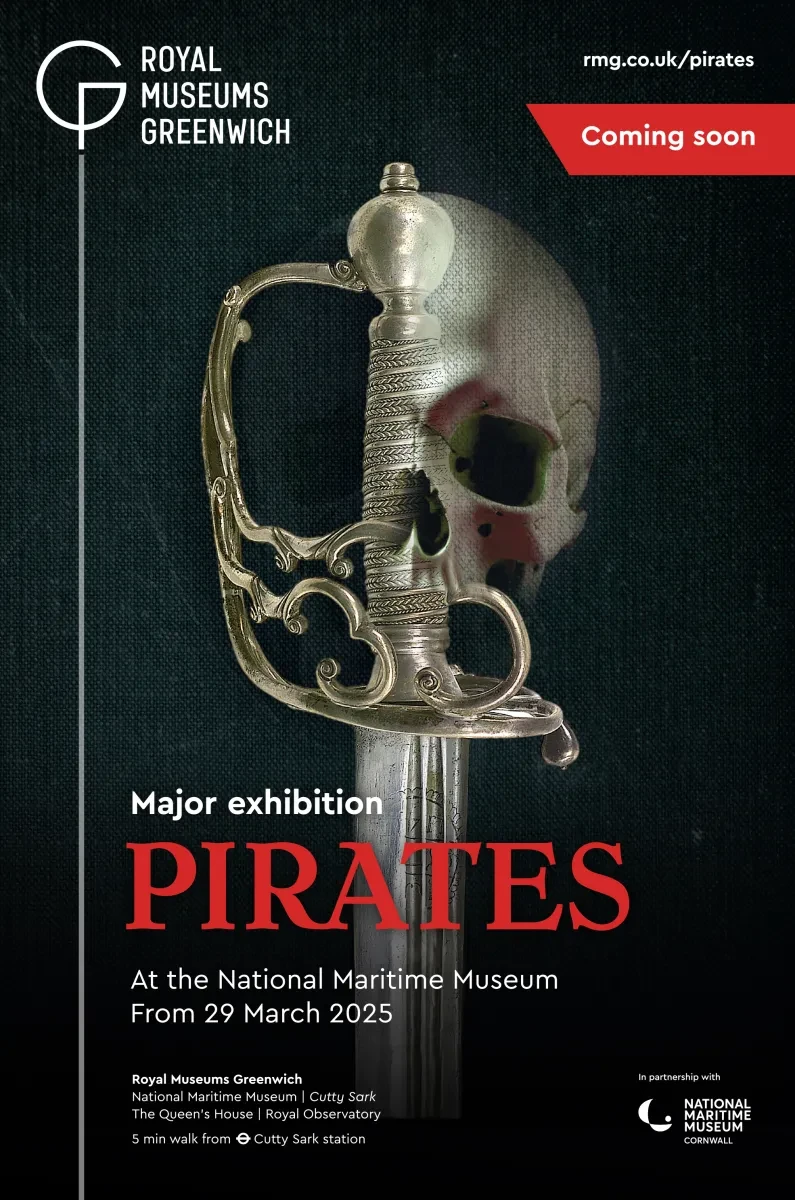

Find out more online with Royal Museums Greenwich. If you want to discover the reality of a pirate's life, set sail for Pirates, a major exhibition now open at the National Maritime Museum.

When was the golden age of piracy?

In the Western world, the period from the 1680s to the 1720s has come to be known as the ‘golden age’ of piracy.

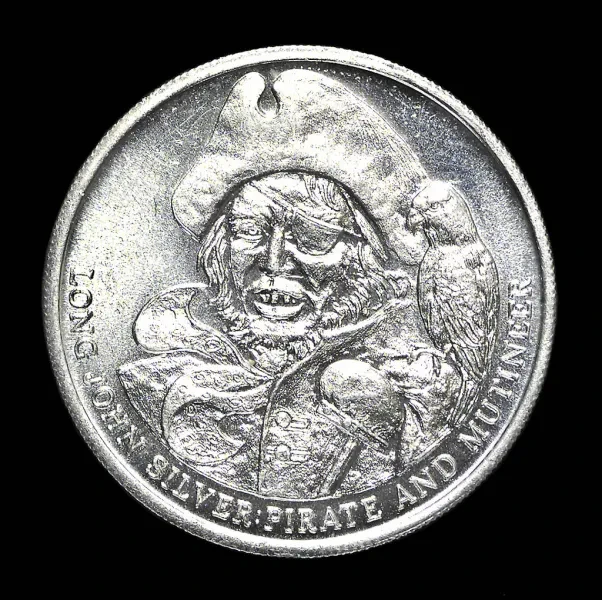

This was a time of heightened pirate activity, when thousands of ships in the Atlantic and beyond became the prey of roving bands of sea-robbers. Many of the most infamous pirates from history come from this era, including Edward 'Blackbeard' Teach, Captain William Kidd, 'Calico' Jack Rackham, Henry Morgan and more.

The Caribbean and the east coast of North America were the main areas that saw a surge in activity in the early 1700s. Ships carrying expensive cargoes were often intercepted, and stolen goods were sold in nearby islands and European colonies. Some pirates operated further afield, off the West African coast or in the Indian Ocean, where the island of Madagascar became a key base.

Ships involved in the transatlantic slave trade were also targeted. While there are some stories of pirates freeing enslaved people, this rarely happened. Pirates often treated enslaved people as badly as their captors did and usually sold them for profit once they reached land.

How do we know what happened during the golden age of piracy?

Piracy captured the public imagination during the 'golden age'. The way that pirates were covered in the news at the time has shaped many of the literary, film and TV depictions of pirates we know today.

"Pirate adventures and courtroom trials made good press stories," according to Dr Robert Blyth, author of Buried Treasure: A Pirate Miscellany. "They featured regularly in early eighteenth-century newspapers and helped shift copies to a public keen to learn the grisly details of the latest pirate heist or the most recent death sentences. But journalists and editors also exaggerated their stories to make pirates appear even more violent and destructive. The ‘golden age of piracy’ was no stranger to fake news!"

Captain Charles Johnson's book A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates, first published in 1724, provides vivid accounts of many of the real pirates from history we're familiar with today.

The book's colourful descriptions and accompanying illustrations have done much to shape our perception of pirates from the past. When describing Blackbeard for example, Johnson writes how his "beard was black, which he suffered to grow of an extravagant length; as to breadth, it came up to his eyes; he was accustomed to twist it with ribbons, in small tails […] and turn them about his ears."

The accounts claim to be based on trial records, newspaper reports and interviews with former pirates. However, Johnson certainly added or exaggerated details to make the narrative more exciting.

The real Pirates of the Caribbean

"The ‘golden age’ of piracy coincided with the expansion of English, later British, colonial activity around the Caribbean," writes Blyth. "This began in earnest with the capture of Jamaica from Spain in 1655."

Rival European powers competed for colonial control, and merchant shipping became a legitimate target for 'privateers'.

"In time of war, British captains might be issued with a privateering commission, or a ‘letter of marque’, which allowed them to intercept enemy shipping and thereby disrupt trade," Blyth says.

"However, habits learned in wartime and the value of captured cargoes meant that privateering could easily give way to peacetime piracy. As the volume of trade increased, the wealth being transported to and from the Caribbean and elsewhere in the Americas became an irresistible temptation."

Why did people become pirates?

For most people, turning to piracy was a way of making money when they lacked other opportunities. The crew of a captured ship might join the pirates to seek their fortune. Becoming a pirate was a risky decision – it could mean death. However, the rewards were potentially far greater than other forms of work at sea.

A life of piracy might also offer freedom from the harsh discipline of a life in the Royal Navy or the hard work and poor pay of merchant shipping. Those who entered the dangerous pirate world usually did so for only a short period.

Pirate hangings in London

For 400 years until 1830, Execution Dock on the River Thames was used as a place for public hangings.

The site was chosen near the low-tide mark, which represented the limit of the Admiralty’s authority. The Court of Admiralty was responsible for the trial and execution of pirates.

Hanging was a grisly affair during the ‘golden age’ of piracy. Unlike in the nineteenth century – when the ‘drop’ was calculated to break the neck, leading to near-instant death – a short rope was used, which left the condemned to strangle slowly to death, which could take up to 45 minutes.

As they fell unconscious, the spasms of their limbs became known as the ‘Marshal’s dance’, named after the court official, or to ‘dance the hempen jig’, referencing the rope. The dead body was left hanging in the noose until at least three tides had submerged it.

– Buried Treasure: A Pirate Miscellany

Why did the 'golden age' of piracy end?

The activities of pirates in the Caribbean, North America, off the West African coast and in the Indian Ocean caused major problems for trade. They became the scourge of the high seas and a menace that governments had to deal with.

During the 1720s, pirates were increasingly hunted down, bringing the ‘golden age’ to an end. Naval power was deployed to intercept pirate ships and bring crews to harsh justice. Amnesties or pardons were also granted, allowing pirates to renounce their criminal past in return for freedom from prosecution.

The fate of the crew of pirate Bartholemew Roberts demonstrates how violent punishment was used to deter would-be pirates.

Roberts, also known as 'Black Bart', was one of the most successful pirates of the 'golden age', who captured and stole from well over 400 vessels during his career. On 10 February 1722 however, his ship was intercepted by Captain Chaloner Ogle of the Royal Navy.

Bartholemew Roberts was killed during the battle, and many of his crew were put on trial in a Court of Admiralty in present-day Ghana. 52 men were sentenced to death by hanging – the greatest number of men sentenced to death at a single trial in an Admiralty court.

Out of these, 18 were found 'guilty in the highest degree'. Following their execution, their bodies were coated in tar and hung inside a gibbet cage as a grisly public warning.

As pirate life became more dangerous and less lucrative, some moved to less patrolled parts of the ocean. Many others decided to give up altogether, effectively ending the ‘golden age’ of piracy.