The River Thames is London's lifeline: source of water and food, hub for trade and a place for pageantry.

For hundreds of years however, it was also the city's sewer.

How have Londoners used – and abused – their river? How polluted was the Thames in the past, and to what extent has the river 'recovered' today?

Is the River Thames safe to drink? The history of London's drinking water

London has always been a thirsty city, but the River Thames isn’t ideal as a source of drinking water.

As the Thames is tidal, its waters are ‘brackish’ – a mixture of fresh and saltwater. Drinking untreated Thames river water is unsafe, although historically it has been used for many domestic and industrial purposes including cooking, brewing and generating power.

People accessed drinking water by collecting it directly from tributaries – the smaller rivers or streams that flow into the Thames – or from communal wells and pumps which tapped into underground springs.

As early as the 13th century, there were complaints about inadequate or dirty water supplies. In response, the City of London built the first organised water system in the city.

It was a large pipe, known as a conduit, which carried fresh water from a spring in the countryside near modern-day Marble Arch, via Charing Cross, Leicester Square, along the Strand, Fleet Street and Cheapside, finally arriving in Poultry. The first pipe, later known as the ‘Great Conduit’, began construction in 1245: it was 2.7 miles long, and comprised of hollowed-out tree trunks and lead pipes.

The water flowed into the city using gravity, ending at a column-shaped building – also known as a conduit or standards – that contained a tank and a tap for dispensing free water to those who needed it. They were guarded by wardens, to ensure businesses like brewers and tanners paid for their supply, and to check private houses weren’t tapping in illegally.

The taps became local landmarks, and for various royal celebrations the conduit on Cheapside was even filled with wine. People either collected drinking water themselves or bought it from water carriers, known as cobs.

As the city grew, other conduits were built, creating a network that was still in use until it was destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire of London.

By this time, new technology was making river water easier to access. In 1582, a Dutch engineer called Peter Morice designed and built a system of waterwheels and pumps in the Thames. This system was the first time London’s water supply no longer relied on gravity alone.

Located in an arch of London Bridge, this system remained in use until the early 1800s, pumping more than four million gallons of water a day.

Another water infrastructure system was created by Sir Hugh Myddleton in 1609. The ‘New River’ was a canal which brought water from springs in Hertfordshire; this canal still supplies some of London’s drinking water today.

As London continued to grow, so did the demand for clean water. Newly established private water companies had to take water directly from the Thames: by 1800, around half of the city’s total water supply, including drinking water, came straight from the river.

New technologies like steam-powered pumps and less-leaky iron pipes all helped Londoners drink and cook, and wash their clothes and themselves.

The River Fleet, despite once being pictured as London’s answer to Venetian canals, became known as the Fleet Ditch. It was eventually covered over and became part of the sewage overflow system, its mouth sometimes visible under the north side of Blackfriars Bridge. It was described by author Jonathan Swift in 1710 as containing:

Sweepings from Butchers Stalls, Dung, Guts and Blood,

Drown’d Puppies, stinking Sprats, all drench’d in Mud,

Dead Cats and Turnip-Tops come tumbling down the Flood.

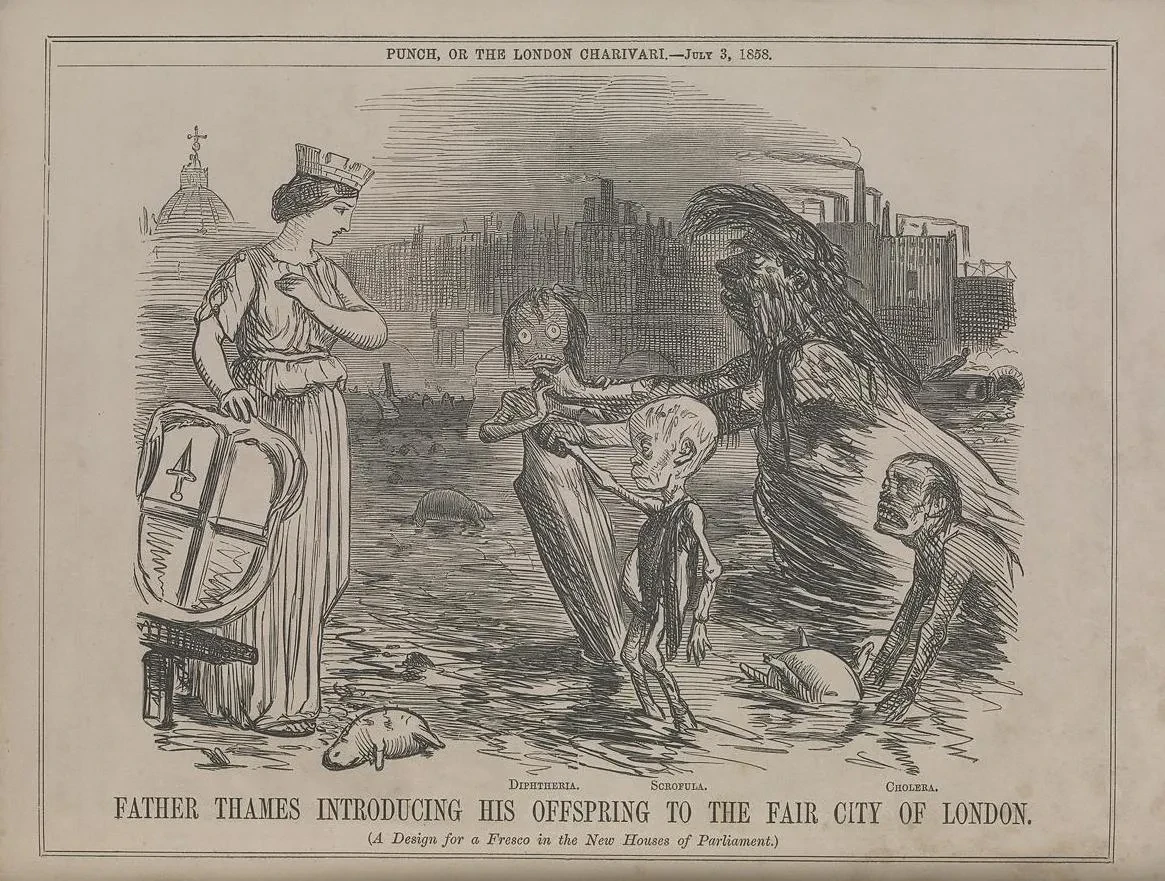

The problems of pollution in the Thames reached a head in the mid-1800s as London’s population grew to above 2.5 million. With more factories and flushing toilets being widely adopted, the volume of domestic and industrial waste flowing straight into the river only increased.

The decrease in water quality began to be linked with disease. In 1850, microbiologist Arthur Hassall described the situation:

A portion of the inhabitants of the metropolis are made to consume, in some form or another, a portion of their own excrement, and moreover, to pay for the privilege.

At the same time, Dr. John Snow’s research showed a link between repeated cholera epidemics and contaminated drinking water, rather than the ‘bad air’ or miasma that previously dominated scientific understanding of disease.

Before the 1800s, the Thames was a rich habitat for both fresh and saltwater aquatic species, making it a natural home for a significant fishing industry.

There were many fisheries in parts of modern-day southwest London, such as Wandsworth, Chelsea and Putney. Fulham was a well-known fishing village. Catch was – and still is, though at a new location – bought and sold at Billingsgate fish market.

In areas towards the sea, sole, cod, herring, sprat and whitebait could be found. Further upstream you could find abundances of smelt, some salmon and eels, which were considered a local delicacy.

As the water quality began to decline in the 1800s, there was a sharp decline in fish numbers. A Natural History Museum study of the Thames in 1957 found no fish at all between Kew and Gravesend.

The Great Stink: London's waste problem comes to a head

In 1852, the Metropolis Water Act was passed, which banned the use of water from the tidal Thames for domestic use, forcing companies to find sources upriver.

The Act also enforced filtering of water, usually using a ‘slow sand filter’ – a layer of sand with shells, gravel and brick beneath that allows water to pass through. A layer of water-purifying bacteria forms on top of the sand layer, providing both a physical and biological filter for the water. This type of filter is still used in London, as well as in remote areas with poor water quality, as it requires very few supplies to build.

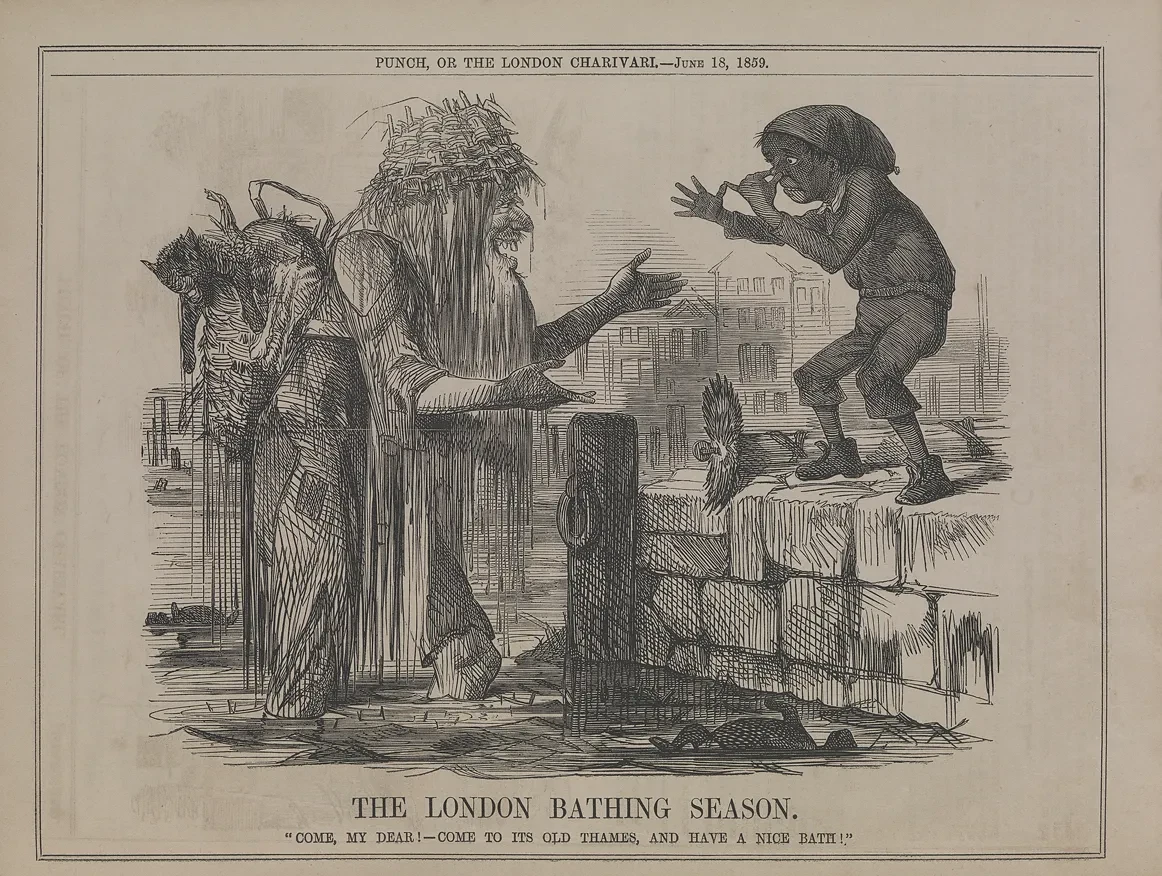

Despite these improvements, the problem was really brought home in the summer of 1858.

Unusually hot weather with record-high temperatures, regularly above 30 degrees Celsius, worsened the smell of the sewage-filled Thames, to the point that politicians were seen fleeing the Chamber of the House of Commons with handkerchiefs covering their mouths to stifle the scent.

Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter on 29 June, after a visit to the newly-built SS Great Eastern: ‘We were half poisoned by the dreadful smell of the Thames – which is such that I felt quite sick when I came home, and people cannot live in their houses’.

Cartoons in newspapers expressed the horror of the stench, and politicians were driven to immediate action.

The Thames Purification bill, proposed by future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, became law in just 18 days.

'Almost all living things that existed in the waters of the Thames have disappeared or been destroyed,' he said. 'There is a pervading apprehension of pestilence in this great city.'

The Metropolitan Board of Works had been established in 1855, tasked with creating a sewage system that avoided dumping waste into the Thames ‘in or near the metropolis’. This bill finally gave them powers and money to get started.

Joseph Bazalgette was chief engineer. His plan was ambitious: a network of 82 miles of underground brick sewers and pumping stations at Deptford, Crossness, Abbey Mills and Chelsea, which disposed of waste east of the city.

The sewers did their job and are still in good condition, having only recently required serious updating to cope with a population more than triple the size they were originally built for.

However, the essential problem of dumping sewage into the river was not solved: it was simply moved further away.

In 1878 the passenger steamer Princess Alice sank right at the spot where the sewers released their waste into the Thames. Many survivors of the initial collision died after ingesting the polluted water.

The tragedy prompted the introduction of what became known as ‘Bovril boats’ (due to the unfortunate colour and consistency of their cargo), which carried sewage sludge out to the Thames Estuary and North Sea, disposing of it there. This continued until 1998, when EU legislation forbade it due to contamination of beaches.

Luckily, the drinking water supply had already been separated from this part of the Thames, so while it was disgusting to see and smell, overall drinking water quality and the health of the city was improved. Modern technologies mean this sewage is now turned into fertilizer for farming.

How clean is the River Thames today?

The Metropolitan Water Board was established in 1902, bringing together existing private companies to make sure that the quality, quantity and cost of London’s water remained consistent, and that new technologies could be brought in quickly. This board was taken over in 1974 by Thames Water.

Conditions were improving up to the First World War, until the increased waste of London’s expanding suburbs set progress back. Second World War bombing damaged sewers, worsening water quality again to the point of biological ‘death’.

By the 1960s the smell of the Thames in warm weather was again notable, and the Port of London Authority and London County Council set about improving sewage treatment and industrial pollution.

"Coming up to London, once we got into the Thames there was an awful smell"

For more than a decade during the 1950s and 60s Gordon ‘Willie’ Williamson transported goods between Ipswich and London.

Working aboard traditional Thames barges, he saw first hand the final years of the Royal Docks as a bustling cargo hub. He also remembers the state of the river at that time.

The smell of London’s sewage can still be smelt today, with sewage still entering the Thames when the system reaches capacity at overflow points along the river, such as at Blackfriars. As the population of London continues to increase, so does the amount of waste and the use of these overflow points.

The discussion of a new sewage system for London has been at the forefront of conversations since the turn of the century. The Thames Tideway Tunnel aims to solve London’s sewage in the Thames problem by capturing the sewage from these overflow points and redirecting them to pre-existing treatment plants. This project began construction in 2015, and aims to be completed by 2025, with a total cost of £4.2 billion.

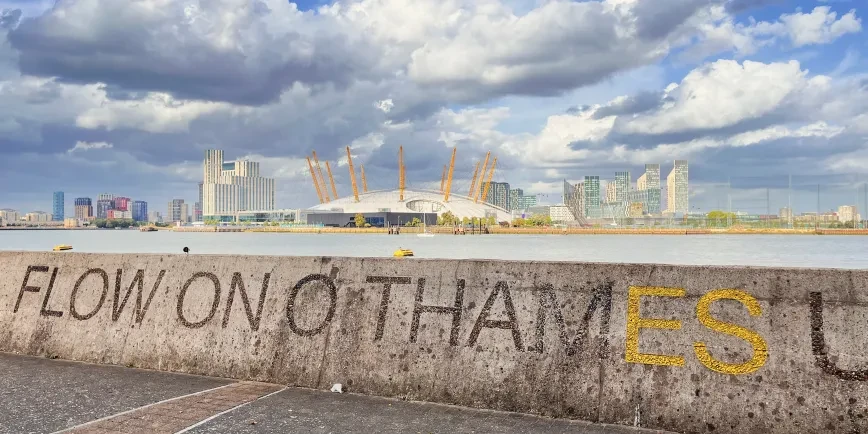

While there is still a long way to go, the water quality is much better and a wide range of projects to encourage aquatic life have been successful. Salmon are spotted occasionally, and studies show 125 fish species and 400 invertebrate species call the Thames home.

This increase in river life brings in bat species, and keystone bird species like herons, cormorants, and Canadian and Egyptian geese. Today, it’s not uncommon to spot grey seals or harbour porpoises in Central London.

Despite the stubborn perception that the river is dirty and lifeless, this is no longer the case. The Thames is currently one of the cleanest city waterways in the world.

The river has been, and will remain, an essential resource for Londoners.

This essay is written by Dr Hannah Stockton, Curator of Maritime London and Merchant Marine at Royal Museums Greenwich. Hannah is currently working on a series of community projects exploring the history of Deptford Creek.

Our relationship with the sea is changing. Discover how the ocean impacts us – and we impact the ocean – with the National Maritime Museum.