The Shipping Forecast is a radio broadcast that provides weather reports for the seas around the British Isles.

First broadcast by the BBC in July 1925, it is an iconic national institution, as beloved and familiar to the British public as fish and chips or the chimes of Big Ben.

To celebrate the centenary of the BBC's first transmission of the Shipping Forecast, the National Maritime Museum and Queen's House are highlighting objects that explore the forecast's history and enduring cultural importance.

Skip to:

History of the Shipping Forecast

The Shipping Forecast was devised by Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy, arguably the first professional weather forecaster. In 1854 he was made chief of the new Meteorological Office (Met Office) and, with a staff of just three people, began collecting weather data to help protect life and property at sea.

The loss of some 450 lives on board the Royal Charter in a devastating storm in 1859 compelled FitzRoy to propose a warning service. He set up a network of stations around Britain’s coasts to collect weather data. Information was sent to ports by telegraph and warning signals were then hoisted to inform ships of incoming storms.

In 1861 the first ‘weather forecast’ – a term coined by FitzRoy – was published in the national press, but it was not until 1911 that it was sent by telegraph to ships at sea. A decade later the first forecast was broadcast by radio and in 1924 the Air Ministry began a service they called ‘Weather Shipping’, transmitted from London.

Smaller vessels lacked the necessary equipment to receive the Weather Shipping signal, so the Met Office turned to the BBC for a solution.

On 4 July 1925 the BBC broadcast the first 'morning weather forecast for Farming and Shipping' from Daventry in Northamptonshire. The first dedicated shipping forecast came in October that year; the format has remained largely unchanged ever since.

Understanding the Shipping Forecast

With thanks to BBC History. Animation by Cognitive. Read by Radio 4 announcer Chris Aldridge.

The Shipping Forecast divides the waters around the UK and Ireland into 31 areas. These areas are mostly named after geographical features, such as sandbanks (‘Dogger’), estuaries (‘Humber’) and islands (‘Rockall’). One exception is ‘FitzRoy’ (originally ‘Finisterre’), which was renamed in 2002 in honour of the forecast’s originator.

The order of the forecast areas is always the same, starting with ‘Viking’ (to the north between Scotland and Norway, hence the name) and moving clockwise around the British Isles. The area – often grouped with others – is announced and followed by its forecast, which begins with wind direction and strength, then precipitation, and ends with visibility. The Shipping Forecast is read at a deliberate, measured pace, as a clear delivery is crucial.

Why do people listen to the Shipping Forecast?

Despite modern onboard technology reducing its importance, hundreds of thousands of listeners still tune in to hear the Shipping Forecast every day.

For some, its slow and soothing delivery helps them drift off to sleep. Others, including the poets Seamus Heaney and Carol Ann Duffy, and the bands Radiohead and Blur, have found artistic inspiration in its ethereal and poetic quality.

In 1998 filmmaker Lucy Blakstad created 'Shipping Forecast, an art installation for the National Maritime Museum featuring footage from different areas of the forecast recorded on a single day.

In our fast-changing world, the Shipping Forecast offers many listeners a sense of stability and a nostalgic reminder of the UK’s maritime heritage.

Follow the Shipping Forecast trail

The Shipping Forecast’s contribution to maritime safety has been invaluable. Take a self-guided tour of the National Maritime Museum and Queen’s House, and discover objects that underline our vulnerability at sea and the importance of respecting the power of our oceans.

Stick barometer, about 1800

Located in the ‘Voyagers’ gallery at the National Maritime Museum

Predicting the weather at sea is important for seafarers who need to check sailing conditions. Sailors began to use barometers in the 18th century to determine changes in the weather, but it was in the 19th century that their use at sea became widespread. This barometer may have once belonged to Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson and it is thought that he later gave it to his friend Captain George Cockburn.

Model of OWS Weather Observer, 1947–52

‘Sea Things’ gallery, National Maritime Museum

Weather ships undertook meteorological observations to support weather forecasting. Initially proposed in the 1920s, they proved their worth during the Second World War, leading to the development of a network of ships in the late 1940s.

Ocean Weather Ship (OWS) Weather Observer began life as a Royal Navy ship (HMS Marguerite) and was converted into a floating meteorological observatory in 1947. Every six hours the Weather Observer’s crew would launch hydrogen balloons to record the temperature, humidity and pressure at 50,000 ft (15.2 km). Since the 1970s the work of weather ships has been largely replaced by satellites.

Fisherman’s charm, coin struck between 1600 and 1800

‘Sea Things’ gallery, National Maritime Museum

Seafarers and their loved ones have always feared the unpredictability and dangers associated with the sea. Many sailors relied on superstitions and lucky charms to protect them. This fisherman’s charm was created from a gold ducat coin struck in Hungary. The Latin inscription reads ‘IN TEMPESTATE SECURITAS’ (safety in the storm).

In the 1960s British vessels were made much safer due to new legislation requiring a working radio to be on board to receive weather reports. This was largely campaigned for by women from the port city of Hull in northern England. Yet fishing remains a dangerous occupation.

‘Sip-and-puff’ helmet, about 2020

‘Sea Things’ gallery, National Maritime Museum

Wight is one of the 31 areas of the Shipping Forecast. This is named after the Isle of Wight, which is often considered to be one of the best places to sail from in the UK. One sailor taking advantage of the favourable conditions is Natasha Lambert BEM. Natasha was born with quadriplegic cerebral palsy, a condition that affects her movement and speech. In 2020 she embarked on a 2,808-mile (4,519-km) journey across the Atlantic Ocean, controlling her yacht using her mouth with a specially designed ‘sip-and-puff’ helmet.

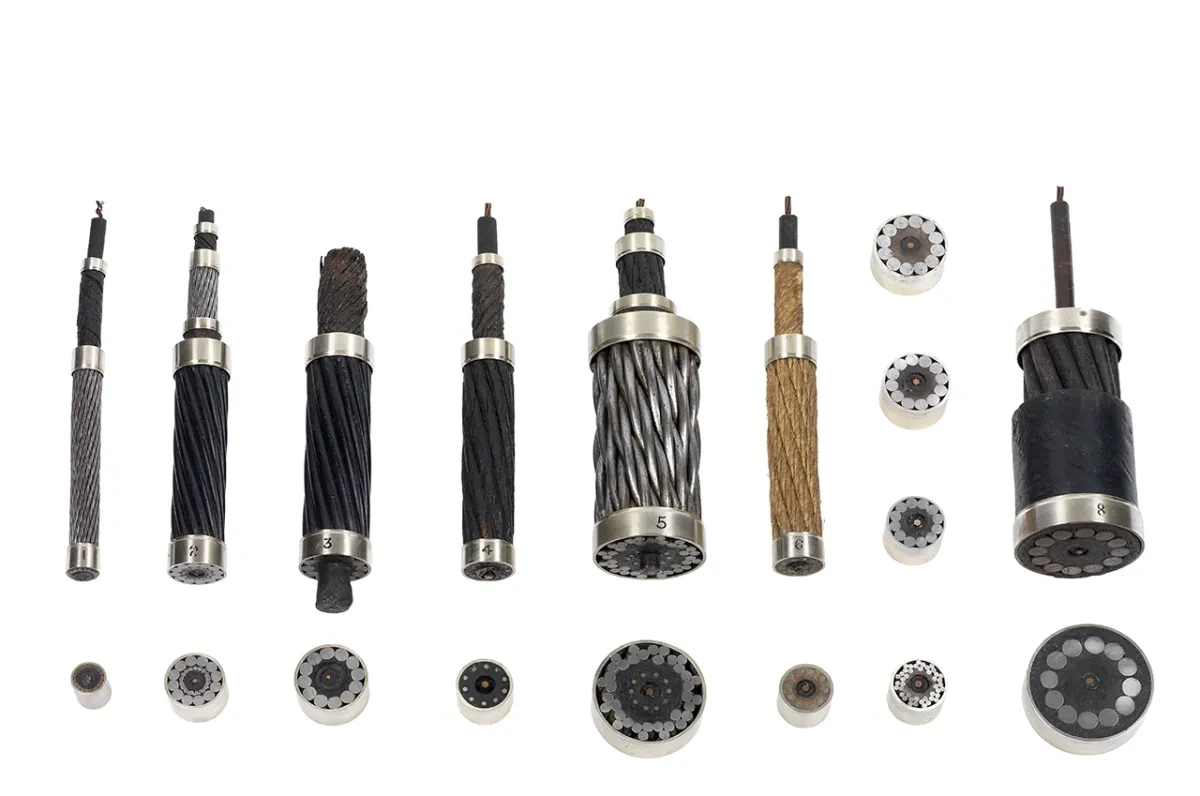

Submarine cable, 1866

‘Sea Things’ gallery, National Maritime Museum

The success of the Shipping Forecast relied on the invention of a practical radio in the early 20th century. Before that, weather forecasts were sent using electrical telegraph communications. While today we are used to accessing information instantly via the internet, most intercontinental information is still carried by cables under the sea (submarine cables), a technology that pre-dates the invention of the radio by several decades. Made for the main transatlantic telegraph, this cable is constructed from copper and iron wires sheathed in hemp, India rubber and pitch. Modern cables are made from fibre optic materials.

Sea Mark by Tania Kovats, 2014

Located on the first floor of the Queen’s House, close to the Bridge Room

Tania Kovats is a renowned British artist who uses sculpture, installation and drawing to explore our experience and understanding of the landscape. Sea Mark is a vast seascape made from hand-painted ceramic tiles. It immerses the viewer in the broken surface of the sea, which recedes to a remote horizon. The shipping forecast for Kovats’s Sea Mark would be ‘visibility – good; smooth; slight; rising more slowly’, corresponding with the meditative quality of the calm, infinite ocean she depicts.

Withdrawal from Dunkirk, June 1940 by Richard Eurich, 1940

Assistant Master’s Library and Drawing Room, Queen’s House ground floor

The Shipping Forecast was not broadcast during the Second World War, but weather conditions at sea played a vital role in the conflict. Following the German invasion of France in May 1940, a flotilla of naval vessels and small boats made repeated trips across the English Channel to rescue British and Allied troops stranded at Dunkirk. The sea remained unusually calm, making the evacuation possible, while light winds blew smoke over the beaches, concealing the waiting soldiers from German aircraft. Based on eyewitness testimony, this oil painting shows the withdrawal in progress.

Mulberry Harbour, Arromanches: Normandy Landing, June 1944 by Stephen Bone, 1944

Assistant Master’s Library and Drawing Room, Queen’s House ground floor

Weather forecasting was central to the planning of the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, known as D-Day. Bad weather on 5 June forced a postponement of the beach landings, but calmer conditions the following day allowed the operation to go ahead. A pair of paintings shows a temporary harbour of floating pontoons, which was rapidly constructed at Arromanches-les-Bains (codenamed ‘Gold Beach’) to help the unloading of vital supplies for the invading force.

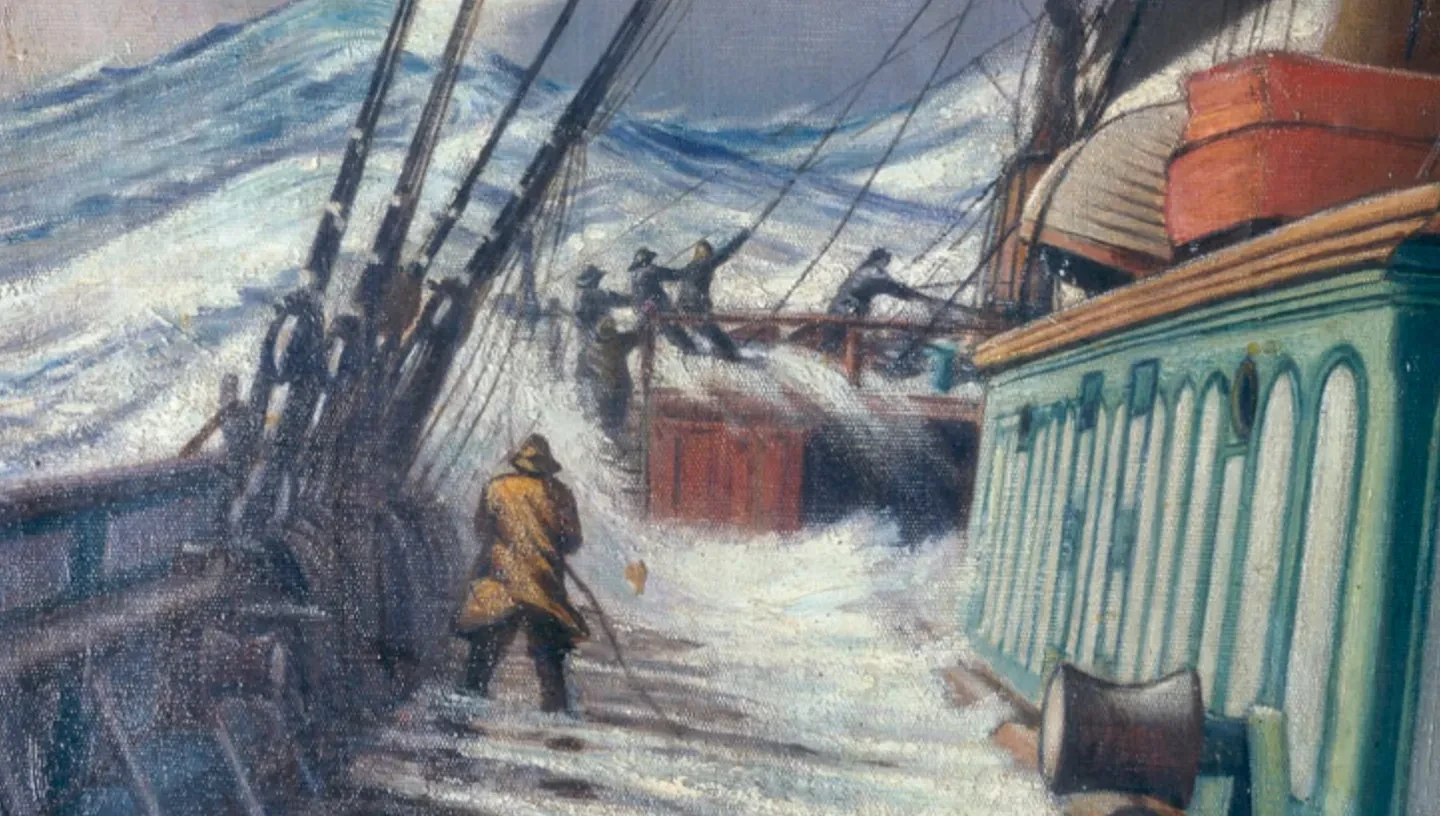

Ships Driving onto a Rocky Shore in a Heavy Sea by Cornelis van de Velde, early 18th century

Governor’s Parlour, Queen’s House ground floor

This small painting has been associated with the Great Storm of 1703, a major weather event that wreaked widespread destruction across southern Britain. The fate of ships in perilous weather conditions certainly loomed large in the British imagination during this period. Dramatic seascapes like this one, most of which did not depict specific events, were very popular on the emerging London art market. This was fuelled by wealthy collectors who were deeply invested in the trade in commodities and enslaved people that was dependent on successfully navigating stormy seas.

Text and collections provided by Royal Museums Greenwich curators: Tim May, Laura Boon-Williams, Katherine Gazzard, Victoria Lane, Simon Stephens and Allison Goudie.

Find more stories you might like

Our partners

Main image: detail from Boarding the far tack on the 'Birkdale' by John Everett (BHC2440)