The recently acquired portrait miniature of Zeenat Mahal marks an historic moment as the first South Asian queen to be displayed at the Queen’s House. This portrait offers a chance to delve into Zeenat’s controversial life, marked by both tragedy and intrigue.

Was Zeenat Mahal a valiant freedom fighter, warrior and expert political strategist – or was she a treacherous murderer? Her contentious story offers insights into how history is written and who writes it, providing a unique perspective on the complex relationship between art and colonialism.

Portrait of a favourite

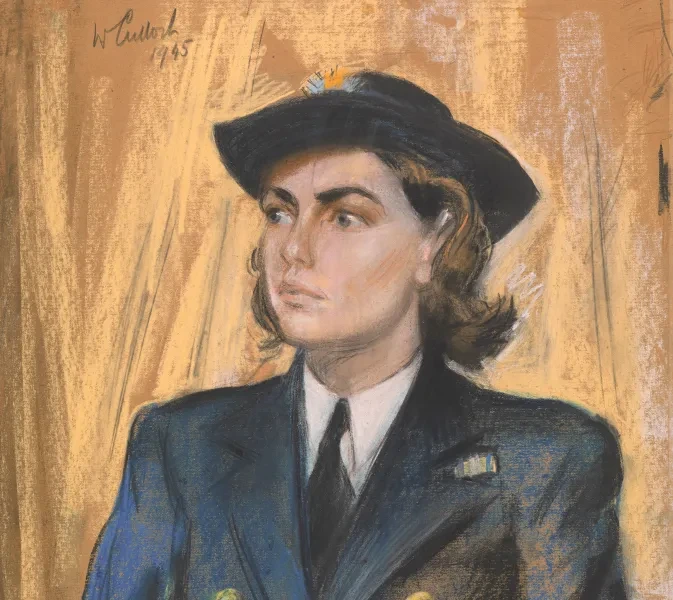

At the age of 19, Zeenat Mahal (1823-1886) married the 64-year-old Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar II (1775-1862). It is believed that this miniature of Zeenat was painted around the time of their nuptials. Their marriage in 1840 was marked by grand celebrations, and she quickly became and remained Zafar’s favourite wife.

When she entered the Mughal court, Zeenat found herself in the midst of a literary renaissance. Ghalib, the greatest lyrical Urdu poet, was writing there, and Zafar himself was a mystical poet, calligrapher, Sufi theologian and scholar. In 1841, she gave birth to Mirza Jawan Bakht, Zafar’s 15th son, and embarked on a determined campaign to secure his position as the heir to the Mughal throne.

Renowned for her intelligence and beauty, Zeenat captivated Zafar, who built her a palace and granted her significant influence at court, eventually making her the de facto regent of the Mughal Empire. Sir Thomas Metcalfe, the Governor-General of India and British Resident in Delhi, complained that Zafar "has surrendered himself so completely to the guidance of the favourite wife Zeenat... that he is induced to commit many unreasonable acts."

Metcalfe’s objections to Zeenat reflect the stark contrast between the Indian and British colonialist representations of the Mughal Queen. While she was known for her astute political acumen and was trusted by her husband (who was more interested in the arts than politics), East India Company officials were frustrated at having to negotiate with Zeenat, leading to their often malicious characterisation of the Empress.

"Clever, wicked woman"

The Mughal Empire, having dominated South Asia since the 1560s, experienced rapid economic decline from the late 18th century. Primarily this was due to the increasing control and expansion of the East India Company, which progressively restricted the Emperor's powers. When Zafar’s eldest son died in 1849, he declared Mirza Jawan Bakht as his successor in accordance with Mughal customs. However, Sir Thomas Metcalfe imposed the alien European concept of primogeniture, thwarting Zeenat’s plans for succession.

Zeenat’s political power and influence were evident when Metcalfe referred to her as a "clever, wicked woman." He even suspected her of poisoning him in revenge for excluding her son. Though there was no proof, the rumours were widely believed within the East India Company. The British colonisers regarded Zeenat’s power at court as dangerous and branded her a murderer.

The East India Company’s egregious acts of corporate irresponsibility eventually led to the largest anti-colonial uprising of the 19th century. The Indian Uprising of 1857 signalled the end of both the Mughal Empire and the East India Company. Indian soldiers (sepoys) initiated the uprising; as it spread, Indian regiments seized Delhi and acclaimed Bahadur Shah Zafar as their nominal leader, albeit not at his behest.

Stories suggest Zeenat opened the gates of the Red Fort at Dehli to the sepoys. However, no evidence supports this claim or that she actively participated in the fighting. Instead, colonial records show Zeenat was negotiating with the British Captain William Hodson for the lives of her family.

In 1858, British forces violently defeated the sepoys and Zafar went into hiding. To secure his life, Zeenat disclosed his whereabouts to the British, leading to Zafar’s capture, trial and the subsequent exile of the Emperor and his family to Rangoon, marking the end of the Mughal dynasty.

While some historians construe her actions as a shocking betrayal of her husband, her supporters point to her shrewd negotiating skills and efforts to ensure her family’s survival.

Zeenat remained devoted to Zafar during their challenging exile, where their living conditions were severely restricted by the British. After Zafar’s death in 1862, the British prohibited anyone from using the title ‘Mughal Emperor’ again. Zeenat lived out her life, in frugality and dignity, until her death in 1886. Her legacy remains intertwined with the grandeur and tragedy of the end of the Mughal era.

Discover more great art

Sign up to the art newsletter for more information about Royal Museums Greenwich's art collection, and learn about upcoming exhibitions and events.

Portrait miniatures and South Asia

South Asian painting developed over hundreds of years, with many ateliers in royal courts. The Mughal court was particularly famous for its art. In 1617, James I’s envoy was presented with a series of Mughal royal portraits, initiating a continual cultural interchange.

South Asia was recognised for its highly significant creative and intellectual culture. Charles I ordered every ship to bring back one Persian manuscript, often containing paintings, due to "the great deal of learning to be known" from them.

The term ‘miniature’ was first used by colonialists, to relate the style of South Asian painting to European medieval illuminated manuscripts and portrait miniatures. East Indian Company officers and administrators became new patrons for court artists, giving rise to the ‘Company Style’.

This hybrid method of painting imposed European tastes on South Asian pictorial conventions, including the introduction of painting with thin layers of watercolour on ivory, as seen in Zeenat’s portrait miniature.

Following the 1857 Uprising, the administration of India passed to the British Crown. Over 3,500 manuscripts were looted from Delhi Library and transported to the India Office in 1859, now part of the British Library’s collection.

The Greenwich connection

Royal Museums Greenwich is actively addressing the gaps in its collection by representing the untold stories of diverse communities and identities. The Museum holds very few portraits of women, let alone diverse ones, making Zeenat’s miniature a highly significant addition, especially as it depicts a powerful South Asian Empress.

Zeenat’s portrait was recently acquired by the Museum through an auction of material belonging to the Grindall family. It is believed that the miniature was collected by the descendants of Rivers Francis Grindall, a senior administrator of the East India Company.

The miniature, probably collected as a souvenir or gift, raises interesting questions about the relationship between the Mughal court and the East India Company. Was this a sign of Zeenat’s fame and power or an exotic objectification of a woman?

As part of a display inside the Queen’s House, visitors can come face-to-face with both the portrait of Zeenat and the family who owned her image.

In this naval portrait of the Grindall family (pictured), made in 1800 by Richard Livesay, a young Rivers Francis Grindall stands between his mother and father, looking out from a domestic scene infused with maritime references.

Zeenat’s portrait is displayed alongside, together with elaborate Chinese and Indian card cases owned by Rivers Francis Grindall and some of the family’s christening clothes. Katherine Grindall, pictured at the centre of the family, would tragically see the loss of all her children, except Rivers Francis.

Zeenat’s portrait miniature, displayed in this context, is a manifestation of colonial power. British imperialism largely celebrates and creates portraits of the colonisers, rarely revealing the stories of the colonised. This absence acts as a central component of imperial domination.

However, Zeenat’s portrait refocuses the narrative to a transnational one, highlighting the entangled nature of these histories and how her story can unexpectedly surface from legacies of colonialism. It also foregrounds her significant role and resilience during the turbulent period of South Asian history in which she ruled and was deposed, oppressed and yet survived, degraded but honoured.

Victoria Lane is Senior Curator of Art and Identity at Royal Museums Greenwich

Find more stories like this