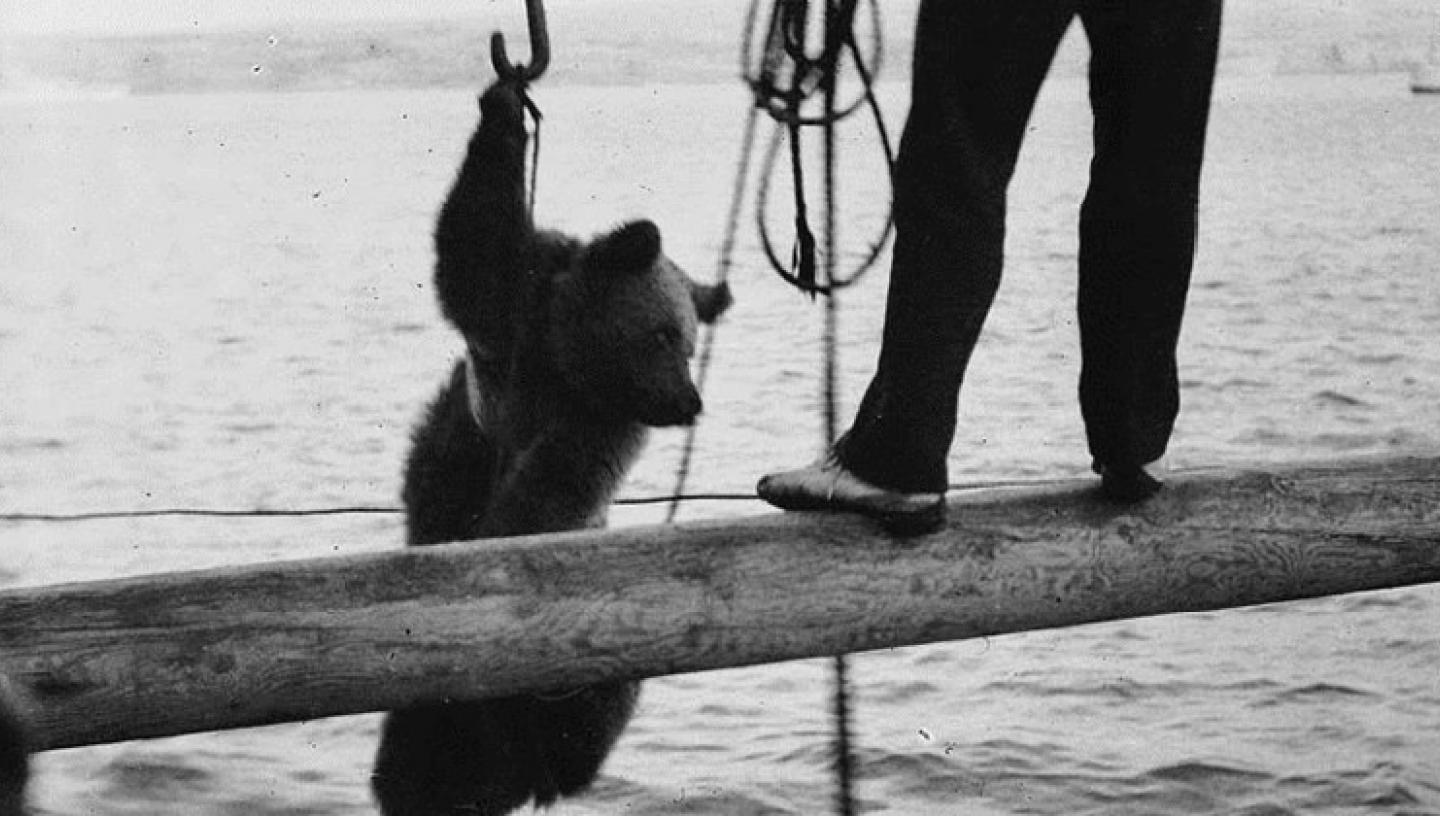

There is a long history of animals and seafarers coming together at sea. Seamen often kept cats and dogs as pets or ship's mascots, but more exotic companions such as parrots, bears and monkeys also joined the crew. Horses, mules and even elephants were transported across the sea to be used in battle, while cattle, pigs, goats and chickens on board provided a source of fresh milk, eggs and meat

By Kaori Nagai, University of Kent and Susan Gentles, Archivist, Access and Cataloguing

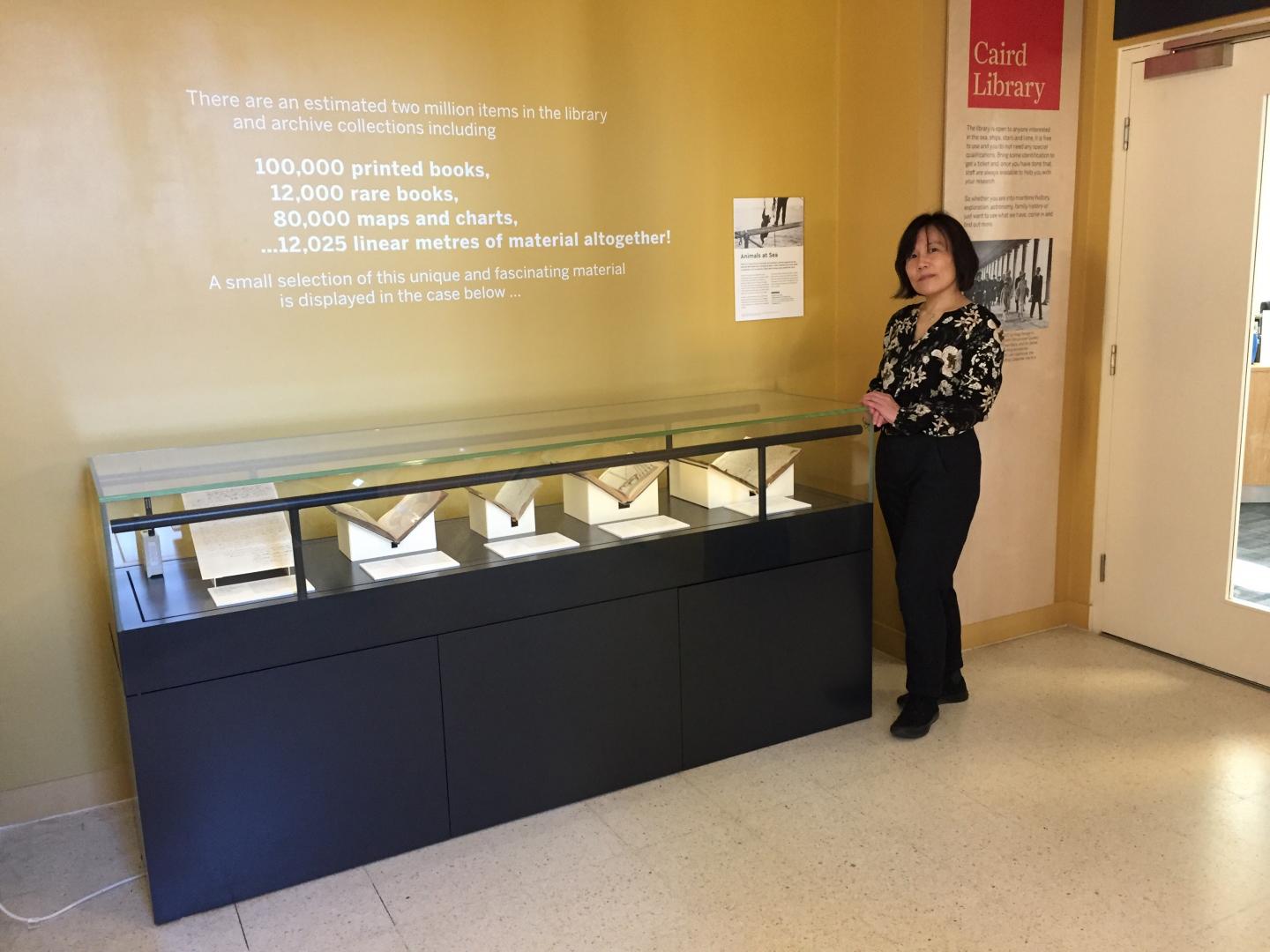

Visit the Caird Library and Archive

Unwelcome stowaways included rats and mice which could do extensive damage to a ship’s equipment and stores, and were usually kept under control by the ship’s cat or dog. Trim the Cat famously accompanied the British naval officer and cartographer Matthew Flinders in his historic circumnavigation of Australia in 1801-03. Flinders’ Biographical tribute to Trim forms part of the display and can be seen in the Museum’s Voyagers gallery.

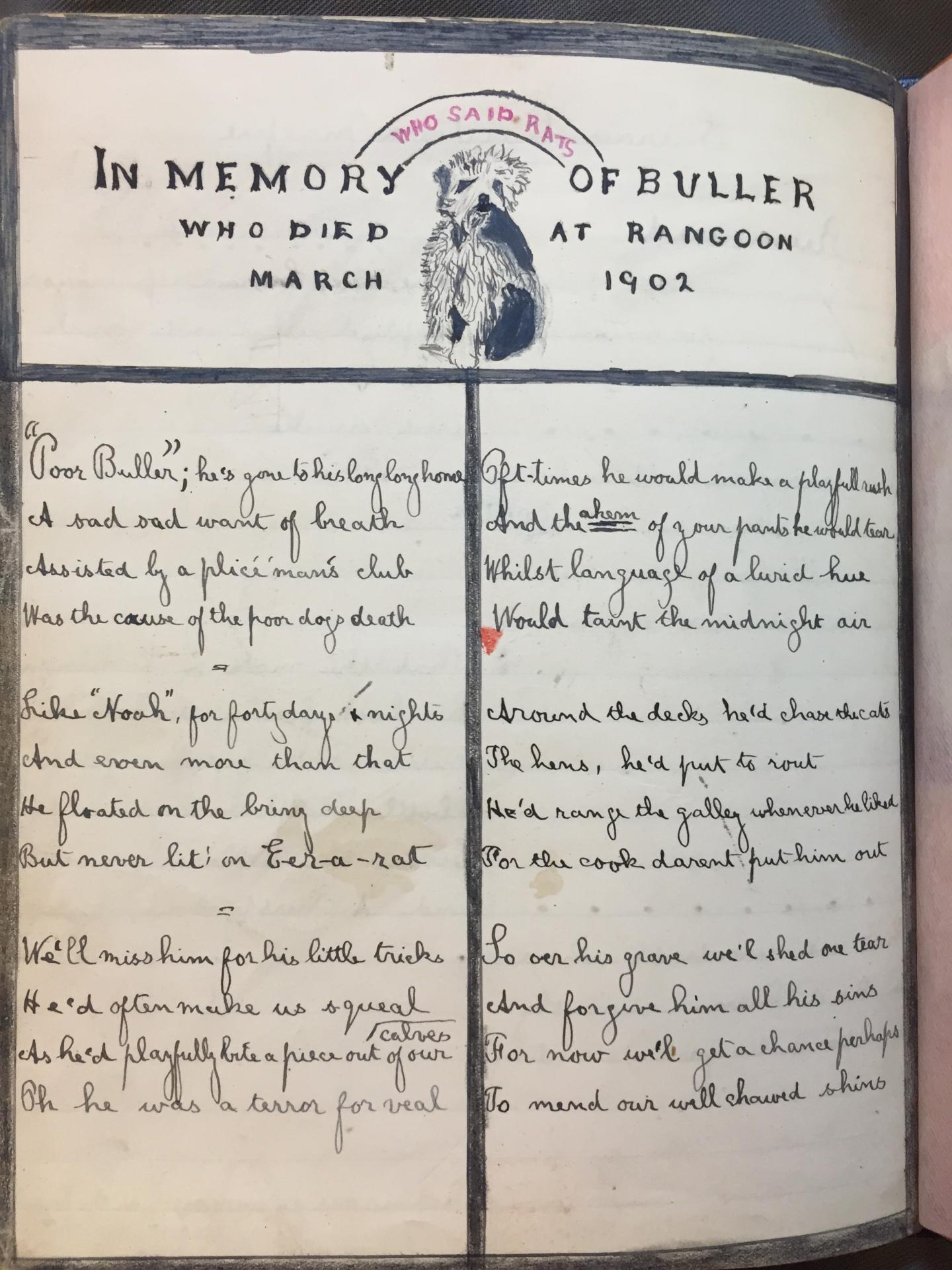

Another item on display, a magazine of a British barque, the Sierra Cordova, features a comical tribute to Buller the dog, the ship’s mascot. Buller entertained passengers with his tricks and mischief, and was often seen chasing cats and chickens around the deck. Buller died after arriving at Rangoon, falling victim to the hot climate. Buller, just like the newspaper, helped to foster a community spirit during the long voyage.

Transportation of animals was considered so important that guidance on how to safely move creatures on and off board ships was frequently included in practical guides. Practical Seamanship for use in the Merchant Service ran to several editions from 1890 to the early 20th Century and was marketed as covering ‘all ordinary subjects and everything necessary to be known by seamen of the present day’. It includes the essential skill of loading horses and cattle on to a ship, illustrating how a horse should be blindfolded and winched on board. The writer stresses the importance of mastering this procedure, as failure to do so ‘would probably mean a broken [horse] leg’, meaning that the horse would have to be shot, and compensation sought from the ship’s owner.

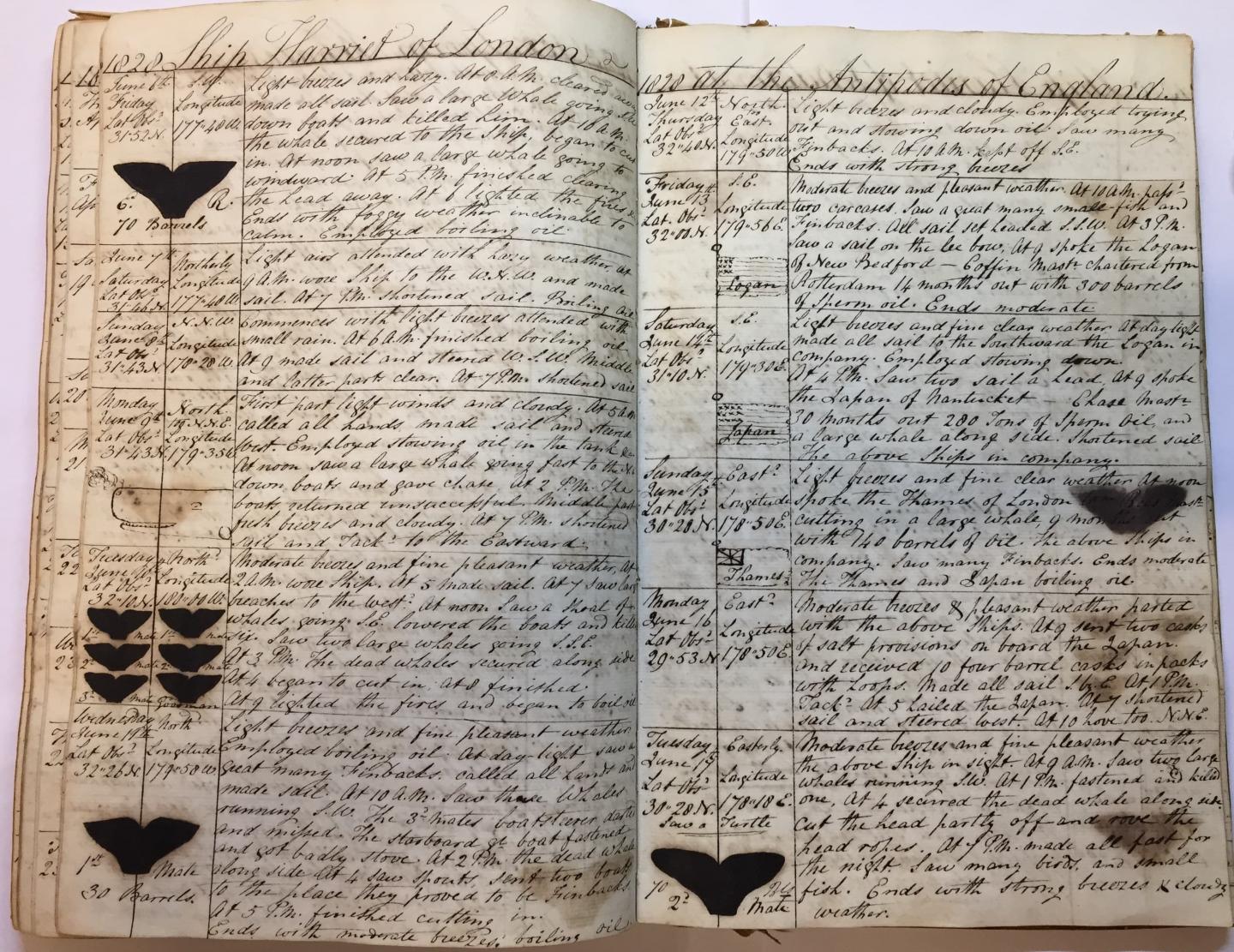

As well as taking animals to sea, sailors also encountered wild animals on their voyages. Seabirds and porpoises followed their ships while animals such as whales were sometimes hunted. In a logbook from the whaling vessel, Harriet, ship’s surgeon William Dalton recounts two English whaling expeditions to the South Pacific in the 1820s. The entries in the logbook, included in the display, give a rare glimpse into life on board a whaling ship. He represented whale sightings by drawing a picture of a whale’s head and successful captures with an image of a whale’s tail: the larger the image, the bigger the whale.

The long tradition of taking animals on board ships came to an end in the 1970s, yet contact between people and animals at sea continued. The display shows some of the different ways this has happened during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The display accompanies a conference called ‘Maritime Animals: Telling Stories of Animals at Sea’ which will be held at the National Maritime Museum from 25 April to 27 April 2019. For enquiries regarding the conference, please see our conference webpages or contact Dr Kaori Nagai (University of Kent) at K.Nagai@kent.ac.uk.

Animals at Sea will be on display until mid-May 2019.