The name Bartholomew Roberts might not be quite as famous as Blackbeard, Captain Kidd or the popular pirates of fiction, but his short-lived career set him apart as a pirate par excellence.

In just three years, he captured hundreds of vessels, making him the scourge of Atlantic trade. His story eclipses the world of pirate fiction.

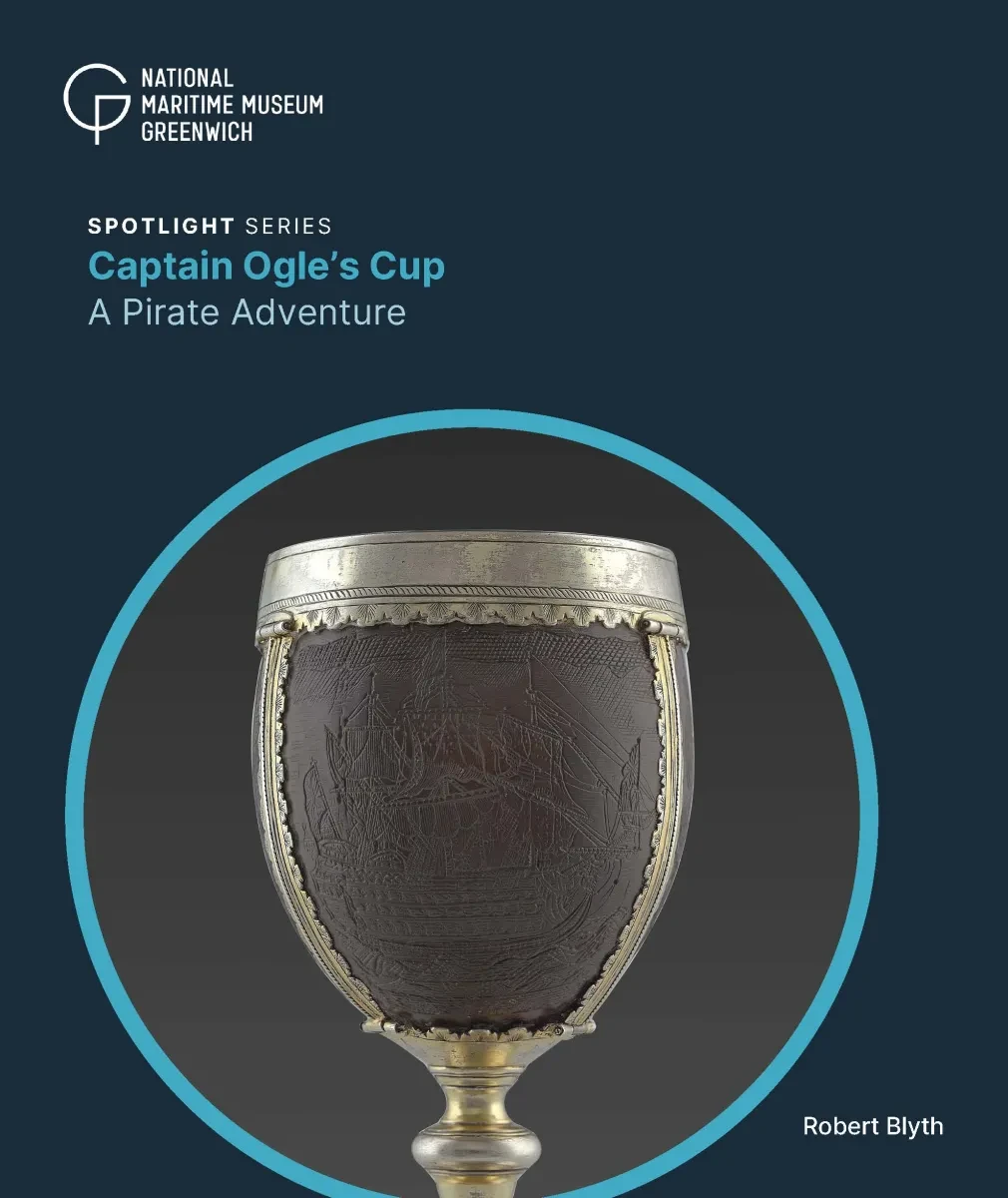

Roberts’s death at the hands of Chaloner Ogle, his nemesis and the owner of this cup, marked the beginning of the end of piracy’s so-called ‘golden age’.

The tale leading to the creation of the cup is one of violence, authority, justice and power. It is a pirate adventure like no other.

This is an edited extract of Captain Ogle’s Cup: A Pirate Adventure by Robert Blyth. The cup will be on display as part of Pirates, a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum.

'A merry life, and a short one’ – the death of Bartholomew Roberts

Captain Chaloner Ogle was given command of 50-gun warship the Swallow on 11 March 1719. After duties in North America and the Mediterranean, he was ordered to West Africa in early 1721. In November he learned that two pirate ships were operating in the region. For Ogle, the hunt was on. But where were the pirates?

Roberts was also in West Africa, where he had been busy raiding ships laden with cargo. At Ouidah, in modern-day Benin, he learnt from an intercepted letter that Royal Navy warships were nearby. Roberts made a hasty departure, leaving just a day before Ogle arrived in the Swallow. It was the narrowest of escapes.

Roberts now sailed to Cape Lopez, in modern-day Gabon, to make his ships ready for a voyage to Brazil. But Ogle was on his trail and spotted the pirate ships on 5 February 1722. The dazzling reign of ‘Black Bart’ as the undisputed ‘king’ of the pirates was about to enter its final, short episode. This time there would be no lucky escape.

When Ogle found his target at Cape Lopez he faced a problem. The Swallow had 50 guns and his men were weakened and diminished in number by disease, whereas Roberts had two ships, with a total of 72 guns, and an experienced crew. The encounter was by no means a foregone conclusion.

The stakes were high: for Ogle, it was a matter of duty, honour and the avoidance of failure; for Roberts, it was about freedom, fortune and, quite simply, his continued survival.

While the Swallow had troubles with disease, the crew of Roberts’s ship, the Royal Fortune, was not in peak condition either, although for very different reasons.

Having recently taken a prize, the hell-raising pirates celebrated by drinking their way through its stocks of liquor. This was done at Cape Lopez on 9 February, making the following morning something of a challenge without the added burden of the sudden arrival of a 50-gun warship. Whether Ogle realised this or not, the odds were moving in his favour.

When the Swallow was sighted again the following day and now identified as a warship, Roberts had to devise a plan quickly. Although his crew was decidedly under the weather, with many of the men still drunk or heavily hungover, he chose to fight.

In A General History of the Pyrates, Captain Johnson describes Roberts on the deck of the Royal Fortune confronting Ogle:

Roberts himself made a gallant figure, at the time of the engagement, being dressed in a rich crimson damask waistcoat and breeches, a red feather in his hat, a gold chain round his neck, with a diamond cross hanging to it, a sword in his hand and two pair of pistols hanging at the end of a silk sling, slung over his shoulders (according to the fashion of the pirates) and is said to have given his orders with boldness, and spirit.

This is exactly how we imagine a pirate captain should appear. But Roberts’s luck finally ran out on 10 February. A series of broadsides from Ogle’s ship rendered the pirates’ vessel essentially immobile, with masts and rigging destroyed.

Roberts’s death was swift and bloody. Grapeshot, dozens of pieces of lead shot used as an anti-personnel weapon, was fired from the Swallow. Some of this struck Roberts in the neck and tore out his throat, killing him at once.

Abiding by his long-held wishes, the crew of the Royal Fortune quickly weighed down his corpse, still dressed in finery, and threw it overboard with little ceremony, denying Ogle the chance to capture the pirate captain even in death. Roberts’s body was never found.

While some of the pirates fought on, they eventually surrendered. With Roberts dead and his pirate crew chained below deck in the Swallow, Captain Ogle was victorious.

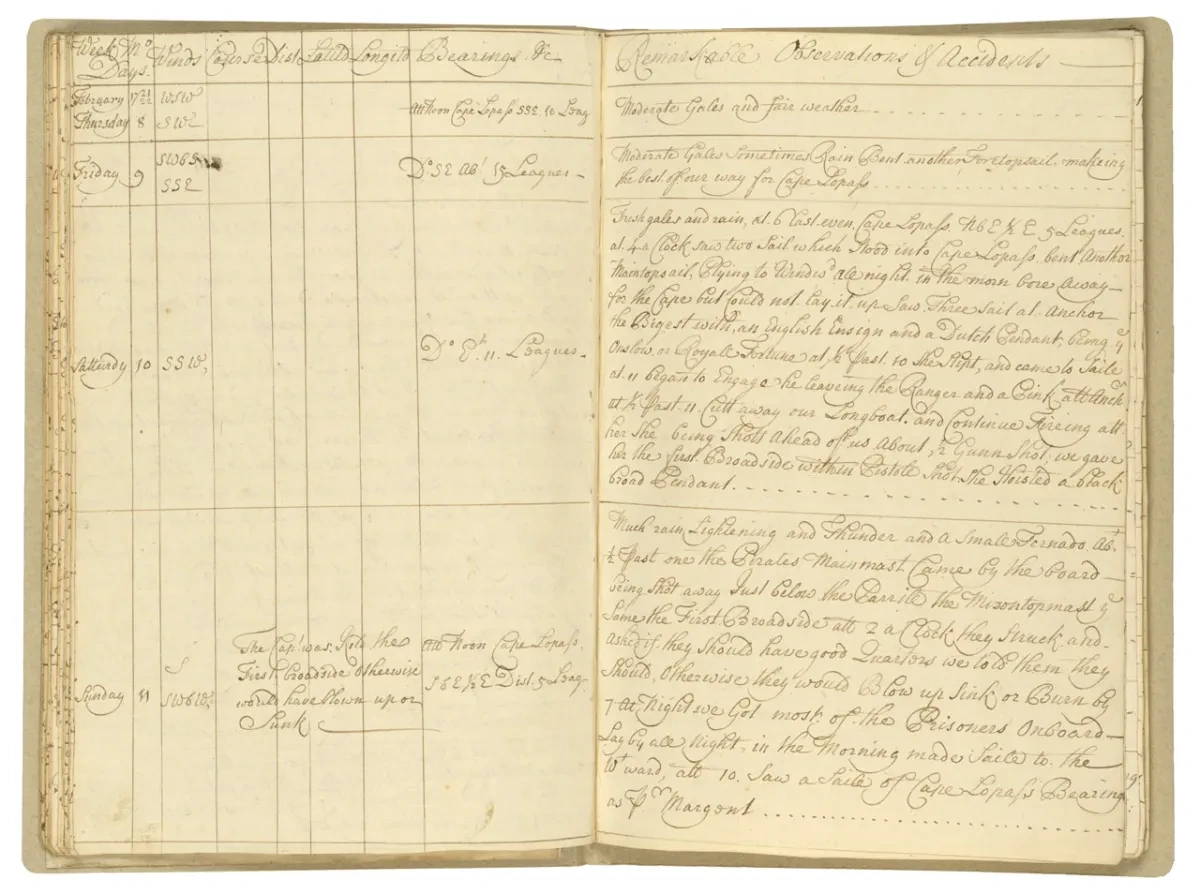

A page from the logbook of HMS Swallow recording the encounter on 10 February 1722 that resulted in Bartholomew Roberts's death.

The pirate hunter’s reward

Following their capture, Roberts’s remaining crew was taken to the Court of Admiralty at British-operated Cape Coast Castle, in modern-day Ghana.

A total of 72 men were sentenced to death: 52 were hanged and 20 had their sentences commuted to seven years of indentured labour in West African mines, effectively a life term given the climate, disease and the harsh nature of the work.

Those pirates who were hanged suffered an agonising end as they slowly strangled to death at the end of a short noose, which could take up to three-quarters of an hour. Towards the end, the unconscious victim suffered involuntary spasms, cruelly known as ‘dancing the hempen jig’. The youngest executed was Joseph More, aged 19, of Mere in Wiltshire; the oldest was Richard Harris, aged 45, from Cornwall. This was the greatest number of pirates ever sentenced to death at a single trial in an Admiralty court.

For Chaloner Ogle, the outcome of the engagement on 10 February 1722 could hardly have been more different. His actions were greatly praised by the authorities in London. He received a knighthood in 1723, becoming the only naval officer to gain such an honour for an anti-piracy operation. Moreover, Ogle was given special permission by George I to retain the pirate ships and the residual ‘treasure’, less the money owed to the other officers and men for the success.

And what about Captain Ogle’s cup? It is tempting to imagine a member of the crew carving the coconut with the fouled Admiralty anchor, the image of the Swallow and Ogle’s coat of arms. It is equally tempting to suppose that Ogle had some of Roberts’s stolen silver melted down to make the mount for the coconut. But we cannot be absolutely certain of any of this.

However, it is improbable that the cup does not relate directly to the incident that gained Chaloner Ogle a knighthood, added substantially to his personal fortune, and rid the world of one of history’s most notorious pirates. While Ogle saw action later in his career that he might have wanted to commemorate, the ships he commanded were larger than the one engraved on the cup, fixing it to his time as commander of the Swallow.

The events of 10 February 1722 changed Ogle’s life and brought that of ‘Black Bart’ to its gory end. The cup is a modest memento that embodies this extraordinary history. It is not only a rare and tangible reminder of piracy’s ‘golden age’, but also a celebration of the now-forgotten pirate hunter, Captain Sir Chaloner Ogle of the Royal Navy.

Read the full story

Captain Ogle’s Cup: A Pirate Adventure explores how Bartholomew Roberts became one of the most successful pirates in history – and considers how his death at the hands of Captain Chaloner Ogle signalled the end of the ‘golden age’ of piracy. The book is part of the ‘Spotlight’ series, which shines a light on special items in the National Maritime Museum’s collections.

Royal Museums Greenwich tends its thanks to D. Gregory B. Edwards for supporting the acquisition of Captain Ogle's Cup, so that it may be enjoyed for generations to come as part of the national collection.

In memory of our friend and colleague Dr Robert Blyth, who had a gift for storytelling and shared his knowledge generously with all who knew him.