30 Nov 2016

The Great Storm of 1703 wreaked havoc across southern Britain, and it remains one of the worst storms in British recorded history.

by Katherine Oxley, Archives Assistant

It has been estimated that the Great Storm of 1703 was more costly in terms of property damage than the Great Fire of London in 1666.

The Caird Library at the National Maritime Museum holds a copy of Daniel Defoe’s The Storm, published in 1704, which includes a compilation of first-hand accounts of witnesses to the storm.

Defoe placed an advertisement in the London Gazette of 2–6 December 1703, to request that men write to him with their recollections:

‘To preserve the Remembrance of the late dreadful Tempest, an exact and faithful Collection is preparing of the most remarkable Disasters which happened on that Occasion, with the Places where, and Persons concern’d, whether at Sea or on Shore.… All Gentlemen that are pleas’d to send any such Accounts, are desired to write no Particulars but what they are satisfied to be true, and to set their Names to the Observations they send, which the Undertakers of this Work promise shall be faithfully Recorded, and the Favour publickly acknowledged.'

The original text from the London Gazette is available to view online (via the 17th–18th Century Burney Collection at the British Library), along with a host of other e-resources, using the public computers in the Reading Room

Defoe was keen to reassure his readers that the accounts in his book were authentic. He wrote:

‘…as most of our Relators have not only given us their Names, and sign’d the Accounts they have sent, but have also given us Leave to hand their Names down to Posterity with the Record of the Relation they give, we would hope no Man will be uncharitable to believe that Men would be forward to set their Names to a voluntary Untruth, and have themselves recorded to Posterity for having, without Motion, Hope, Reward, or any other reason, impos’d a Falsity upon the World, and dishonor’d our Relation with the useless Banter of an Untruth.’

He also explained that the letters that appeared in his book were not edited to any great extent, the better to preserve the first-hand nature of the accounts:

‘And tho’ some of the Letters inserted are written in a homely Stile, and exprest after the Country Fashion from whence they came, the Author chose to make them speak their own Language, rather than by dressing them in other Words make the Authors forget they were their own.’

The Navy was badly hit by the storm. Defoe’s book includes the account of Miles Norcliffe, who was on board a ship which survived the storm, the Shrewsberry; from where he witnessed the sinking of several naval ships, as well as many more merchant ships, at Goodwin Sands:

‘Sir, These Lines I hope in God will find you in good Health, we are all left here in a dismal Condition, expecting every moment to be all drowned: For here is a Great Storm, and is likely to continue ; we have here the Rear Admiral of the Blew in the Ship, call’d the Mary, a third Rate, the very next Ship to ours, sunk, with Admiral Beaumont, and above 500 men drowned : The ship call’d the Northumberland, a third Rate, about 500 Men all sunk and drowned : The Ship call’d the Sterling Castle, a third Rate, all sunk and drowned above 500 Souls : And the Ship call’d the Restoration, a third Rate, all sunk and drowned : These Ships fired their Guns all Night and Day long, poor Souls, for help, but the Storm being so fierce and raging, could have none to save them….There are above 40 Merchant Ships cast away and sunk : To see Admiral Beaumont, that was next to us, and all the rest of his Men, how they climed up the Mast, hundreds at a time crying out for help, and thinking to save their Lives, and in the twinkling of an Eye were drown’d...’

In our archive stores we also hold original correspondence from the Admiralty to the Navy Board that relates to the ships and men lost in the storm.

One letter, dated 14 December 1703, sets out instructions for paying the wages of the drowned officers:

‘Whereas I think it fitting that the ships which were cast away in the late violent Storme, should be paid…I doe therefore hereby desire and direct you to cause the Wages due to the Commanders Officers and Companys of the severall Ships…to be paid to such persons as shall be lawfully Empowered to receive the same, without expecting any accounts from the Officers of them, in regard their Books & Papers were lost with them. And you are not only to begin to pay the said Ships this day Month, but to take care to give Notice in the Gazette of the times when each particular Shipp will be paid for the better satisfaction of the Wives & other Relations of the persons deceased.’

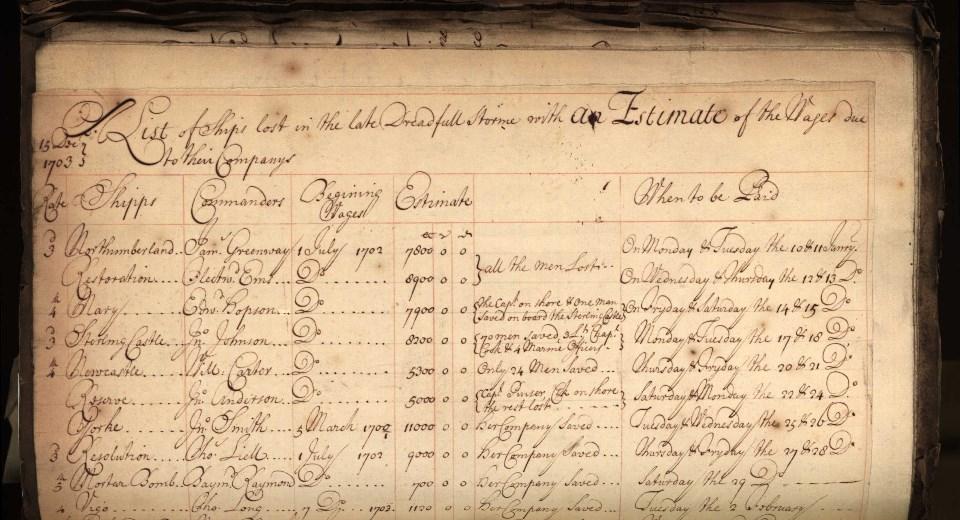

The letter is followed by a list, dated 15 December 1703, of ships lost in the storm as well as an estimate of the wages that were due:

This letter and the accompanying list form part of a manuscript from the Admiralty Collection which can also be viewed in the Reading Room.