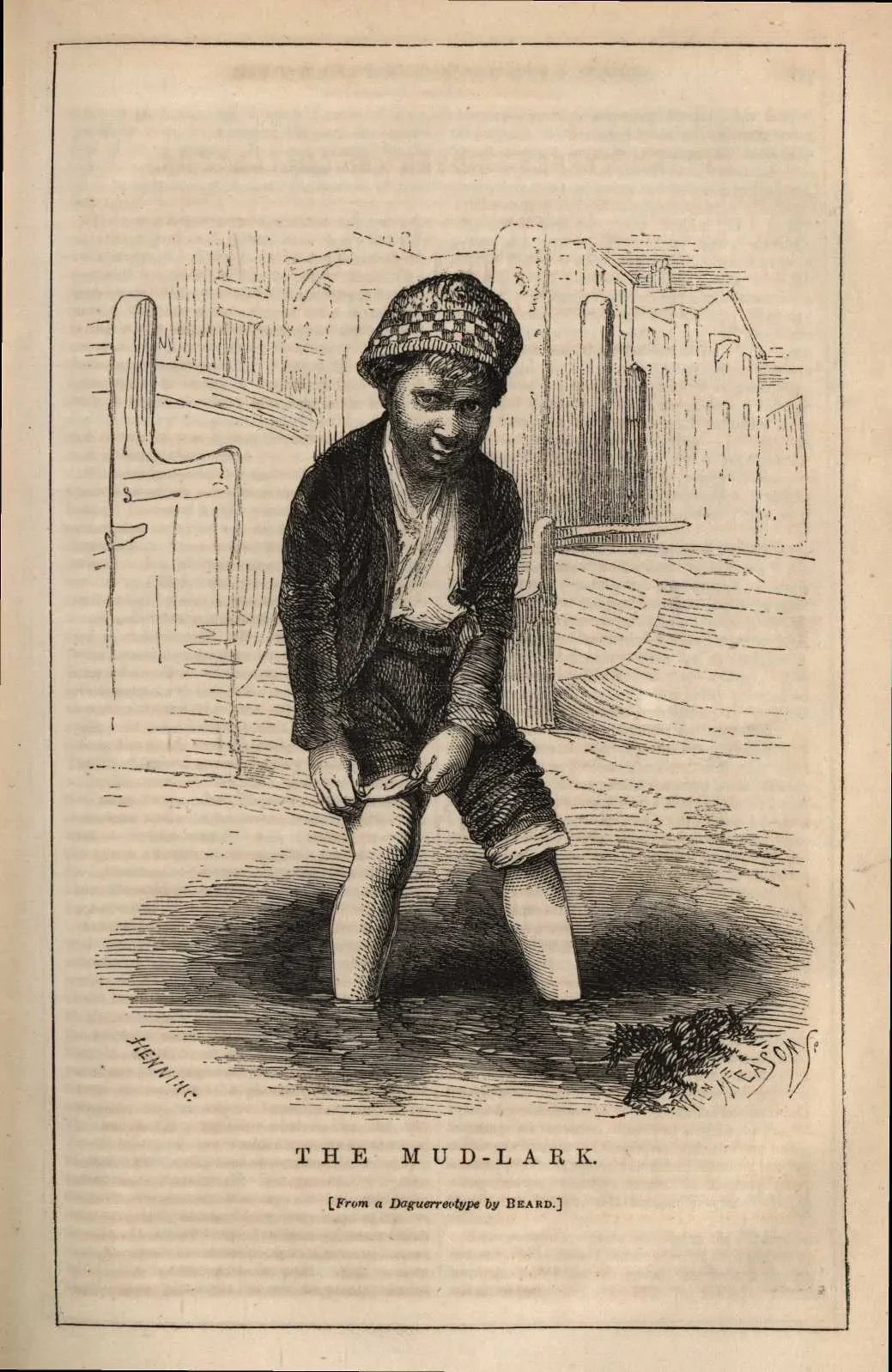

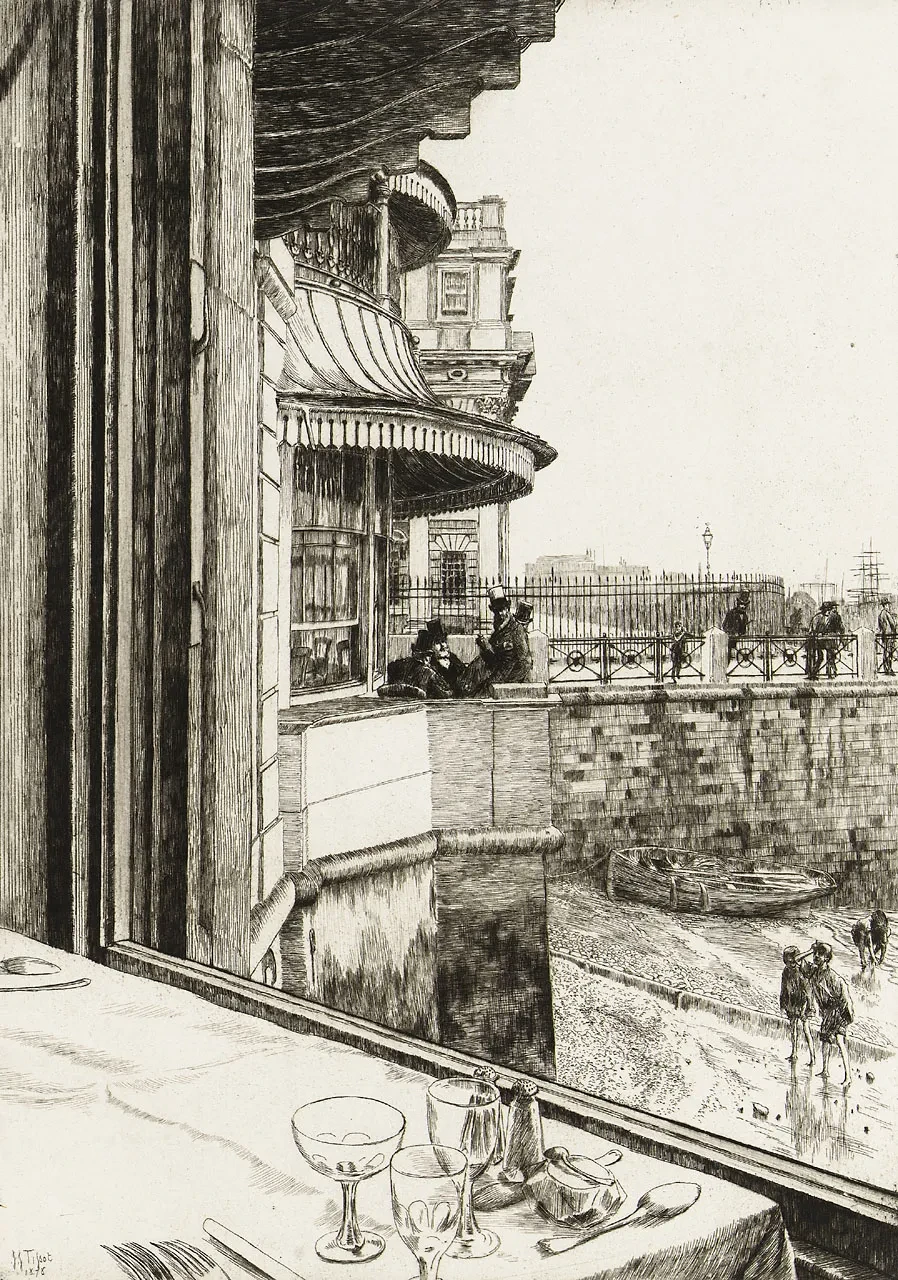

If we were able to return to Victorian London and head down to the banks of the Thames at low tide, we could observe silent human figures aged from childhood upwards, bent over, wading (sometimes waist-high) in the wet mud

Their ragged clothes and limbs would be coated in the foul-smelling mud which included all manner of detritus, but it was within the mud and sewers that they searched for the modest riches which had been thrown away, dropped or lost overboard from the vessels moored on the Thames. These bent, bedraggled figures of humanity were the mudlarks, scavengers in London’s river and sewers who scratched a living by selling the articles they found.

The journalist and chronicler of the Victorian underclass Henry Mayhew (1812-1887), wrote that ‘These poor creatures are certainly about the most deplorable in their appearance of any I have met with in the course of my inquiries.’

According to Mayhew, most mudlarks lived near the river and would gather by the river banks when the tide started to ebb. When the water level was low enough, they would disperse and commence their labours among the vessels moored on the river’s edge. Stooping down, they would peer in the mud searching for ‘coals, bits of old-iron, rope, bones, and copper nails that drop from ships while lying or repairing along shore.’ Mudlarks operated from Vauxhall Bridge eastwards to Blackwall (on the north bank) and Woolwich (on the south). Those working near the shipyards at the eastern end earned more because they were able to scavenge items, such as wood, iron and copper nails, washed out from the yards in the tide.

Mudlarks lived on the margins of the law, sometimes stepping outside it. Mayhew recorded that:

‘Sometimes the younger and bolder mud-larks venture on sweeping some empty coal-barge, and one little fellow with whom I spoke, having been lately caught in the act of so doing, had to undergo for the offence seven days’ imprisonment in the House of Correction: this, he says, he liked much better than mud-larking, for while he staid there he wore a coat and shoes and stockings, and though he had not over much to eat, he certainly was never afraid of going to bed without anything at all – as he often had to do when at liberty.’

Mudlarks sold coal to the local poor, and took iron, bones, rope and copper nails to rag shops, or might sell fragments of pipes or other objects to a collector who appeared on the river bank. If they found tools, they usually took these to seamen, who exchanged them for ‘biscuit and meat’. Mayhew believed their average earnings to be 3d. a day. Boy mudlarks might moonlight at the cab stands, opening doors for boarding passengers or keeping hold of the horses.

One of the occupational hazards which mudlarks faced was injuring their bare feet on sharp objects such as nails and broken glass. One child mudlark whom Mayhew interviewed had:

‘Some little time before I met him […] run a copper nail into his foot. This lamed him for three months, and his mother was obliged to carry him on her back every morning to the doctor.’

In 1867 the author and journalist James Greenwood recounted the story of another mudlark who ventured up a sewer, got disorientated when the light faded outside, and, stuck in the sewer pipe in a stooping position, endured the rising water level at high tide, accompanied by the bites of rats.

Though mudlarks were among the poorest of the poor, for some, at least, it was possible to escape the occupation. The boy mudlark mentioned by Henry Mayhew was helped by one of Mayhew’s friends, who got him a job at a printer’s. The mudlark who suffered the sewer ordeal became a crossing-sweeper.

If you would like to find out more about mudlarks, the Caird Library and Archive has copies of the following items:

Amsel-Arieli, Melody, ‘The Mudlarks’, in Family Tree Magazine, August 2017, pages 69-71

Mayhew, Henry, London Labour and the London Poor, Vol II, London: Griffin, Bohn and Company, 1861 (RMG ID: PBF5076)