Royal Museums Greenwich is home to the National Maritime Museum, Royal Observatory Greenwich, historic ship Cutty Sark and the Queen's House.

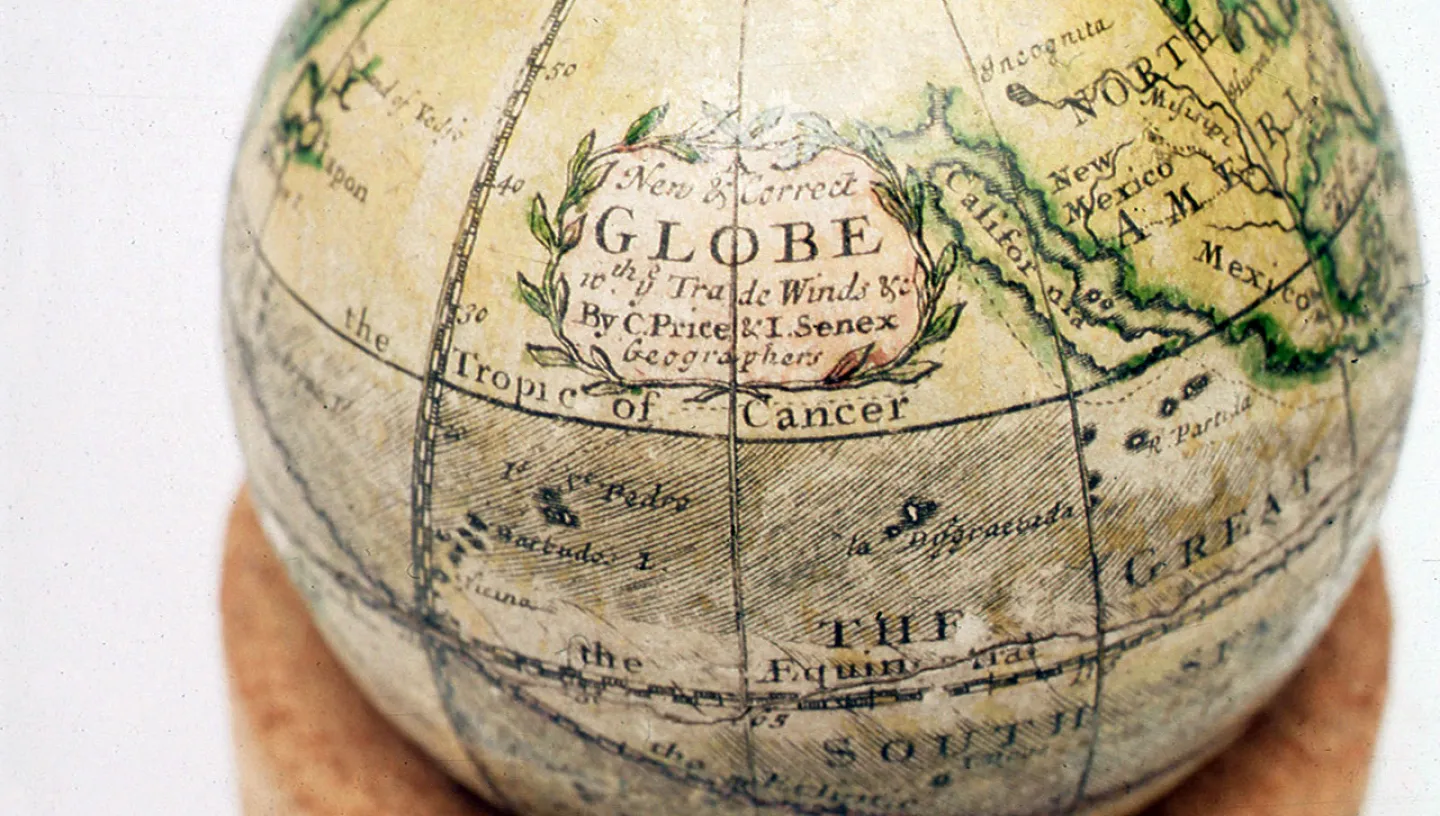

The museum collections include over 2.5 million items and offer a window into maritime life, scientific enquiry and artistic achievement.

Browse online articles, hear from museum curators, astronomers and special guests, and take a deep dive into our collections and archives.

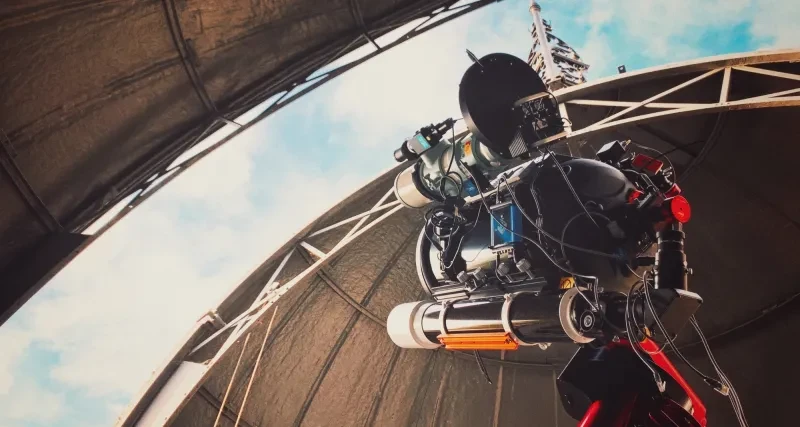

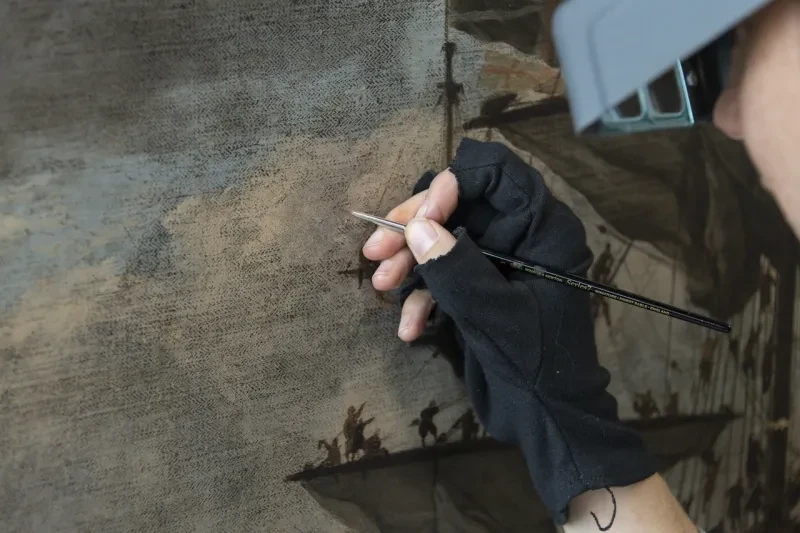

A history of the Royal Observatory in six objects

Explore 350 years of the world-renowned institution and the people who worked there through six intriguing objects

Search the collection

Explore our digital collections or visit our library, archive and collections studio in person

Support stories like these

Royal Museums Greenwich is a charity, and we rely on your support to care for our collections and allow everyone to discover the wonders of space, time, history and creativity. Donate today and help shape the Museum's future.