A mermaid is a mythical sea-dwelling creature, often described as having the head and body of a woman and a fish's tail below the waist.

Stories of mermaids have existed for thousands of years and span cultures across the world - from coastal settlements in Ireland to the landlocked Karoo desert in South Africa. The English word mermaid is a compound of "mere" (Old English for sea) and "maid" (a girl or young woman).

What does a mermaid symbolise?

With such a rich and varied history, the symbol of the mermaid is as changeable as the sea itself. In some cultures, the mermaid signifies life and fertility within the ocean. In others, she embodies the destructive nature of the water, luring sailors to their deaths — serving as an omen for storms, unruly seas and disaster.

Here are a few of the myths and legends of mermaids that have reached our shores:

Africa: Mami Wata

In West, South and Central Africa, a range of tales exist about mythical water spirits called Mami Wata (meaning "Water as Mother" or "Mother of the Waters").

As these spirits or divinities stem from multiple African cultures with ancient roots, there is no singular characteristic to their identity. Mami Wata's gender is fluid, meaning she can sometimes appear as a man or woman. The spirit is worshipped for both their benevolence in offering beauty, healing and wisdom, and as a way of warding off natural disasters.

Following colonialism and the rise of the slave trade in the 1600s, the stories and beliefs of Mami Wata spread across the globe and remain an important source of spiritual connection with African communities seeking to reclaim their traditions and cultural identities.

Ancient Greece and Rome: Sirens and Mermaids

The mermaids of Greek and Roman mythology are considerably close to the appearance and character of the European myths we think about today.

Many ancient Greek myths equate sirens with mermaids. However, while they share many characteristics, they are now seen as two different entities.

A famous Greek folktale claimed that Alexander the Great's sister, Thessalonike was transformed into a mermaid upon her death in 295 BC and lived in the Aegean sea.

Whenever a ship passed, she would ask the sailors one question: "Is King Alexander alive?" If the sailors answered correctly, declaring "He lives and reigns and conquers the world," Thessalonike would allow the ship to continue on its journey. Any other answer was said to anger her, and she would conjure a storm and doom the vessel and its sailors to a death at sea.

Eastern Europe: Rusalki

Often translated as "mermaid," the Rusalki are water nymphs of Slavic mythology.

While initially regarded as benevolent spirits of fertility and agriculture, Rusalki gained a more sinister description in the 1800s. They were believed to be the ghosts of women who died violent deaths by drowning. In their anger and sorrow, the Rusalki now lured men and children to their watery graves.

Ireland - Merrows

Female merrows, with their beauty and long green hair, resemble our traditional views of mermaids. Their counterpart, the male merrow is considered grotesque, cruel and more fish than man. The ruthless nature of the male merrow is why the creatures were said to have relationships with humans.

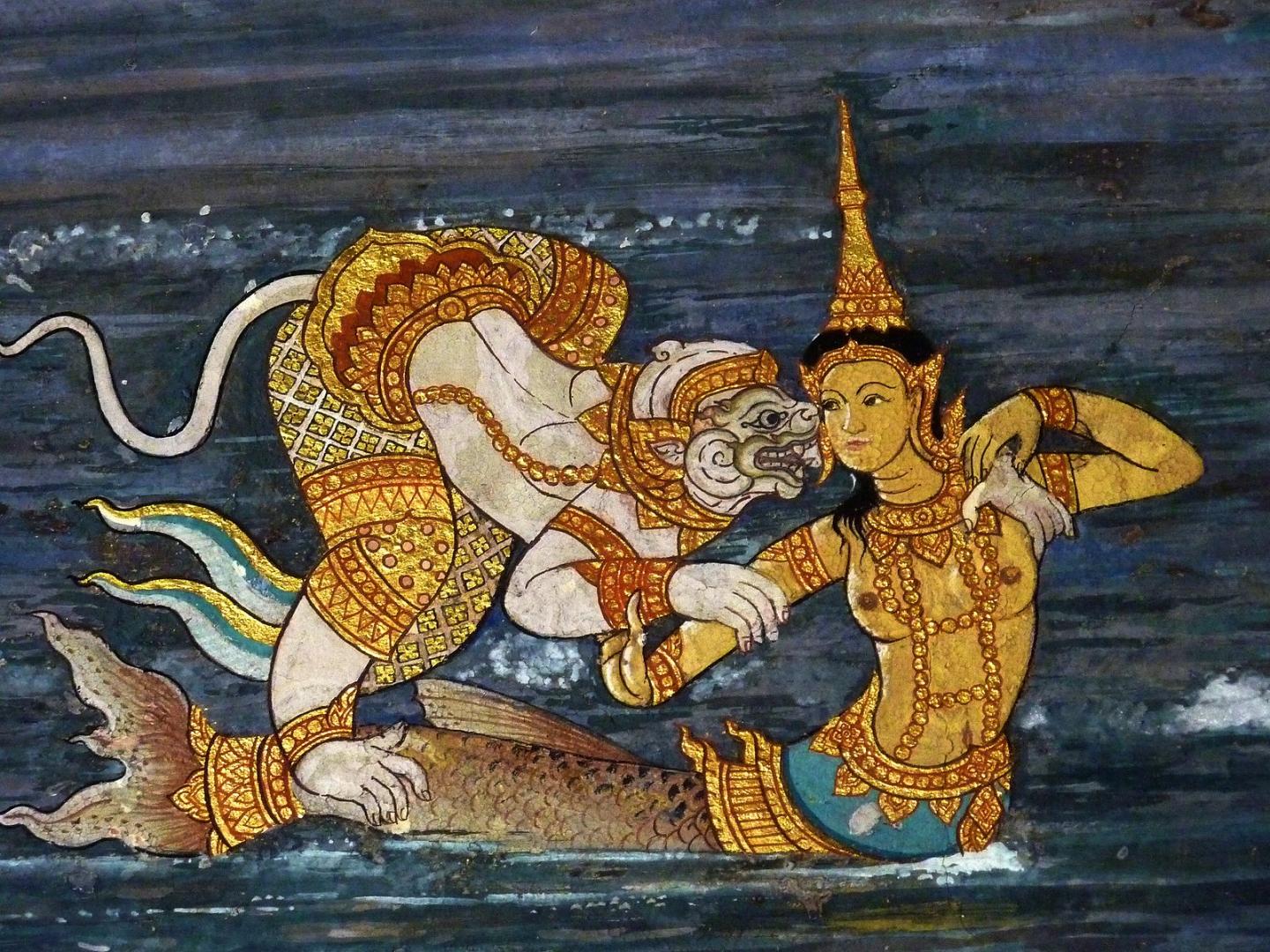

Southeast Asia - Suvannamaccha

Southeast Asian folklore includes the story of a mermaid princess, Suvannamaccha (meaning "golden fish").

In the Ramayana, the countries retellings of the Indian epic poem, one of the heroes, Hanuman attempts to build a bridge of stones across the sea.

His plans are hampered by Suvannamaccha who has been instructed to prevent the causeway's completion. The two meet and fall in love and Suvannamaccha ends up helping Hanuman finishing the path. The mermaid is now seen as a herald of good luck and her figure is depicted in charms, streamers and icons throughout Cambodia, Thailand and Lao.

Scottish Isles and Scotland - Selkie

While not exactly "fishy" the Scottish selkie has often been connected to mermaid mythology.

These shape-shifting creatures live as seals while in the sea and transform into humans while on land. In Gaelic stories, they are often described as "maighdean-mhara" meaning "maiden of the sea." In their stories, selkies are uncertain creatures. There are stories of them tempting people into the water, but others where they cast off their seal skins, marry humans and begin families.

These tales usually end in tragedy when the selkie returns to the oceans, with or without their loved ones.

Western Europe: Melusine

A feminine spirit found in many medieval European folktales, the Melusine has a serpent or fish's tail and sometimes has wings. Hungary, France and Germany all have different accounts of Melusine. The most famous legend describes her as a willful girl who tries to get revenge on her human father on behalf of her fairy mother, only to be punished by her mother with a tail.

Contemporary symbols

More recently, the figure of the mermaid has been adopted by the transgender youth network, Mermaids UK.

Founded in 1995, this organisation supports children and young people who are transgender and/or gender diverse. The symbol of the mermaid provides a potent symbol to the community due to the mermaid's ability to transform. With the absence of physical genitalia, the sex of the mermaid is irrelevant.

Person of the Sea is a sculpture by Eve Shepherd. Commissioned by Royal Museums Greenwich, the sculpture was created after Shepherd spent two years working with trans and gender diverse youth at Mermaids UK.

What are the origins of mermaids?

How far into humanity's past, our stories of mermaids reach is unknown — possibly since we first began finding creatures in the sea. Archaeologists have found accounts in Mesopotamian mythology of Oannes, a male fish-god from over five thousand years ago.

One of the earliest mermaid legends appeared in Syria around 1000 BC when the goddess Atargatis dove into a lake to take the form of a fish.

As the gods there would not allow her to give up her great beauty, only her bottom half became a fish, and she kept her top half in human form. Archaeologists have found Atargatis' figure on ancient temples, statues and coins.

While the early Britons such as the Celts have folktales of mermaids, no illustrations have been uncovered.

The earliest depiction of a mermaid in England can be found in Norman chapel in Durham Castle, built around 1078 by Saxon stonemasons. It is a strange carving, with the mermaid found alongside two leopards and several hunting scenes. Historians believe the mermaid symbolises the temptations of the soul.

Are mermaids lucky?

In sailor folklore, mermaids represent both good fortune and disaster. As sailors spent months, sometimes years travelling across vast oceans; it's not surprising that beliefs and superstitions of figures controlling the unpredictable weather appeared in nautical stories over the centuries.

The mermaid's conflicting personalities as both a beautiful and seductive maiden and a monstrous sea creature that dragged sailors to their deaths is a fitting representation for the wild, violent yet fascinating nature of the sea itself.

Mermaids often appear as figureheads on the front of nautical vessels. The figurehead, which was popular between the 16th and 20th centuries is a carved wooden decoration located on the bow of ships. While many different decorations have been used, mermaids proved popular with the sailors as they were believed to appease the sea, ensuring good weather and finding a safe way back to land.

Early mapmakers such as Olaus Magnus, used sea monsters (including mermaids) to portray dangerous geographic areas of the oceans - places where bad weather and shipwrecks were frequent.

To this day, shipwrecks are frequent when vessels are coming into land. Running aground can happen for any number of reasons, such as changes in water depths or navigating errors, but this may explain why sirens or mermaids were said to congregate in these regions.

What is the difference between a siren and a mermaid?

In early Greek mythology, the sirens were half-women, half-bird creatures and are often confused with mermaids. This misconception has led to the word siren being used instead of a mermaid, such as "sirène" in French.

While mermaids are morally ambiguous creatures, sirens were said to be always malicious and dangerous, attracting sailors with their captivating voices towards the hazardous rocky coast of their island.

In Homer's epic poem, The Odyssey, the titular hero of the story ties himself to the mast to hear the song of the sirens without destroying his ship. This story is where our term, "siren song" originates, referring to a request that is hard to resist but that, if heeded, will lead to a catastrophe.

Sirens cited in classical literature

- Aglaope ("Splendid Voice")

- Parthenope ("Maiden Voice")

- Ligeia ("Clear-Toned")

- Leucosia ("White Substance")

- Thelxiope ("Charming Voice")

- Thelxinoe ("Charming the Mind")

- Thelxipea ("Charming Song")

- Peisinoe ("Affecting the Mind")

How are mermaids depicted in art?

With such rich folklore, there have been numerous depictions of mermaids in literature and art.

The Little Mermaid

One of the most famous stories is Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid. Published in 1837 in Copenhagen, Denmark as part of a collection of children's fairy tales, the story has been adapted to many different forms of media, including theatre, opera, and, most popularly, a Disney animated film in 1989.

Andersen and Disney's versions of the tale have noticeable differences. In Andersen's story, the mermaid princess loses her tongue to obtain legs and every time she walks; her pain is compared to "walking on knives." While the Disney tale concludes with the heroine and the prince marrying, Andersen's story is somewhat more tragic. The princess fails to undo her curse and the prince marries someone else. The little mermaid sacrifices herself and ends up living with the "spirits of the air".

In 1909, the Danish sculptor Edvard Eriksen was commissioned to create a statue inspired by Andersen's fairy tale. The bronze sculpture has remained a popular tourist attraction and icon of Copenhagen since its unveiling in 1913.

Armada Portrait

Look closely at the Armada portrait of Queen Elizabeth I and you may notice a mermaid carved into the chair of state.

Historians are conflicted whether the mermaid imagery is simply a typical piece of Renaissance decoration or connected to the two ship scenes above. The mermaid may represent Elizabeth's ability to provide calm seas to her English fleet and summon tempestuous storms for her Spanish rivals, much like a mermaid. Whatever the case, the depiction is a potent image of a lone queen exerting her power as her subjects fought at sea.

Mary Queen of Scots, the Mermaid & the Hare

Interestingly, the symbol of the mermaid also appears in a series of illustrations of Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth's cousin and rival for the throne. However, these sketches were made with very different intentions. Following the murder of Mary's husband, Henry Stuart (also known as Lord Darnley) on 10 February 1567, these allegorical posters of unknown origins began appearing around Edinburgh. The signs allude to Mary as a mermaid and her future third husband, James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell as a hare.

In these symbolic drawings, the mermaid represents a figure of temptation and prostitution, while the hare symbolises a lustful animal. As propaganda, it promotes Elizabeth as the virtuous, "virgin queen" while implicating Mary in the death of her second husband and portraying her as a prostitute.

Catching a Mermaid

In James Clarke Hook's painting Catching a Mermaid (1883), we have a merging of reality and childhood fantasy.

Hook shows a young boy hauling the figurehead of a mermaid from a beautiful but turbulent sea, while two other children watch from behind a rock. The lighthearted title belies the potentially tragic disaster of a ship lost at sea.

Allegory: the Ship of State

In Frans Francken I's (1542–1616) painting, Allegory: the Ship of State (late 1500s), Francken depicts a Spanish ship filled with Catholic dignitaries attempting to navigate a path through a series of treacherous islands with volcanoes, meteorites, giants and wolves. The allegory of the title refers to the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato's often cited metaphor (comparing the command of a state to that of a naval vessel).

The painting alludes to the political upheavals of the time between Europe and Spain, and the Protestant revolt against the Roman Catholic Church. In the front and centre of the painting are two mermaids admiring themselves with mirrors. The mermaids here may represent the dangers of a shipwreck from drawing too close to the rocks and the vanity of the figures on board.

The Sea Maidens

This beautiful painting by de Morgan (1855-1919) shows five mermaids embracing each other and staring out at the viewer, perhaps towards a shoreline.

The painting is part of a series, linked to Andersen's The Little Mermaid. The scene is thought to relate to the heroine's five sisters wistfully visiting the shore after she has transformed into a human, the forlorn looks upon their faces could signify their desire for their sister to return to waters with them.

The painting displays Evelyn's profound appreciation for colour and mastery of the brush, noticeable in the vibrant iridescence of the mermaid's scales.

Discover more about this painting and the life of Evelyn de Morgan