In a world of bright deckchairs and beach huts, black and white photographs demand that we look at the seaside differently.

The Great British Seaside: Photography From The 1960s To The Present runs from March 23 to September 30 at the National Maritime Museum. Find out more

By Kristian Martin, Exhibition Curator

A trip to the seaside is filled with colour. From the natural blues, greys and yellows of the sea, sky and sand to the primary colours of deckchairs, windbreaks and beach huts, it is a vibrant experience. The things we take with us – hats to keep off the sun, buckets and spades to build sandcastles and picnic boxes to keep our sandwiches cool – are all suitably brash. Even the food we associate with the seaside has a unique colour scheme: baby pink candyfloss, unnaturally yellow chips, bright orange ice lollies and sugary rock in a variety of neon shades all enhance the joy and playfulness of a visit to the beach.

This is nowhere better captured than by Martin Parr, a photographer who sits at the heart of the National Maritime Museum’s current special exhibition, The Great British Seaside: Photography from the 1960s to the present. Parr’s work is flooded with the colours that are such an important part of this unique place and are an essential motif of his own distinctive and much-loved style. When Martin Parr began photographing the seaside in the 1970s, however, he worked in black and white. The absence of colour in these early works makes them unrecognisably Parr, yet there is an unexpected poignancy to many of them and they still show his keen eye for the peculiarities of seaside behaviour.

Today, for Martin Parr colour and the seaside are intimately linked. When you ask him why he is drawn to photographing Britain’s beaches he usually mentions the ‘vibrant and jolly’ colours that you will find there. He moved to colour in the early 1980s and his mastery of it is clear in the striking seaside-themed The Last Resort series (1986) made soon afterwards. Here he photographed New Brighton in Merseyside using daylight flash which saturates the pictures with colour. His switch to colour was partly inspired by the seaside postcards of John Hinde where the colour was artificially enhanced and is on the very edge of gaudiness. They show British resorts where the sun always shines and where a black and white seaside experience would be unimaginable.

![New Brighton, Merseyside, 'Last Resort, 1983-85 [MP07] (Magnum Photos)](/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_1440/public/LOA2225%20New%20Brighton%2C%20Merseyside%2C%20%27Last%20Resort%2C%201983-85%20%5BMP07%5D%20%28Magnum%20Photos%29%20%28LON6985%29_0.jpg?itok=OV_UHvd3)

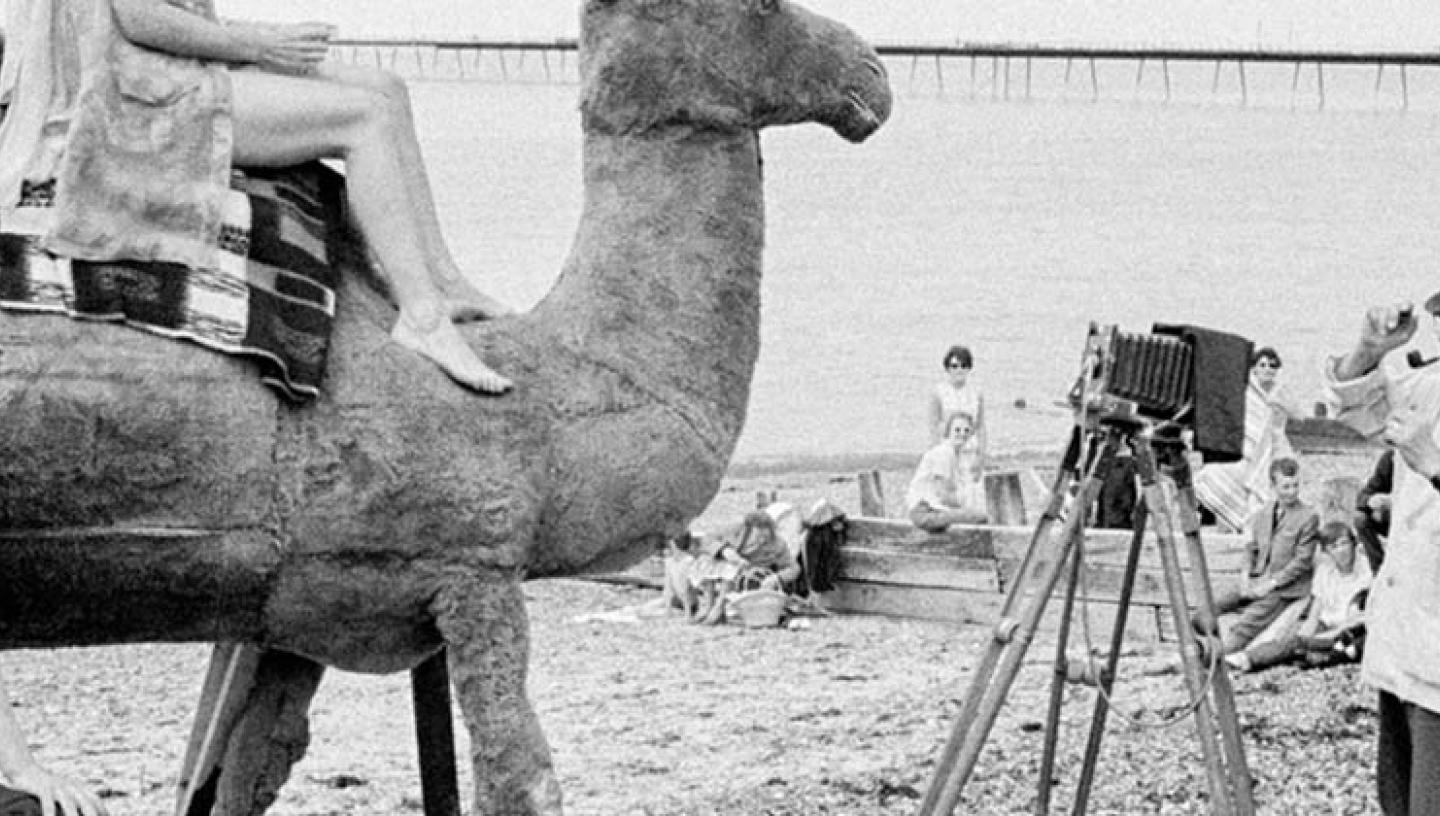

Yet some of the most evocative and beautiful seaside photographs have been shot in black and white and this approach can add so much to how we see the British beach experience. Forty of the works on display in the Great British Seaside exhibition, those by Tony Ray-Jones and David Hurn, are black-and-white pictures. These clearly show the appeal and suitability of the medium in capturing a moment, an event or an encounter on the beach in a very different way.

When Tony Ray-Jones began his photographic career in the 1960s black and white was the dominant medium. It was the easiest film to obtain and process, was more reliable than early colour film and was the classic and most respected style for art and documentary photography. His use of black and white may have therefore been driven by necessity rather than being a conscious artistic choice. Towards the end of his short life he was using colour photography and probably shot more in colour than he ever did in black and white. Yet his black and white beach photographs, many published posthumously in the book A Day Off, have a clarity, observational quality and timelessness which are harder to find in his colour work.

In a similar way, David Hurn says that he suspects he began photographing in black and white simply because it was what his local chemist stocked at the time. He says:

The temptation is to eulogise about Henri Cartier-Bresson and Bill Brandt, who of course both shot in black and white, but the reality is that, back in 1955, I would not have known who either was.

Hurn has taken colour photographs during his 60-year career – in fashion shoots and celebrity portraits for instance – but black and white dominates his back catalogue. His documentary photographs, which he prefers to call ‘reportage’, are almost exclusively monochrome and this continues to be his preferred medium. Hurn explains why:

I think it is because I am primarily interested in the way people react to each other emotionally. Black and white produces no distractions from that core idea. If I shoot a picture of two people in some sort of embrace, and one of them is wearing a bright orange sweater, the picture becomes first a fashion shot before we realise it is actually about the relationship between the two people. Colour is so powerful it overpowers. Or maybe I just find black and white easier, I think I see photographically in black and white, but there again that might be just fantasy.

Black and white photographs certainly demand that we look at the seaside differently. Colour can disrupt or dominate the scene and without it, shapes, patterns, textures and form are heightened in the image. Black and white cuts to the very soul of what is going on, by focussing the eye on the picture’s composition and the people, objects and events in it. Black and white can also emphasise light and shadow which is such an important part of the seaside experience. It can create a specific atmosphere and give beauty, power and sensitivity to a scene. One of the photographs in the exhibition that demonstrates this so well is David Hurn’s striking picture taken in 1997 at Whistling Sands, Porthor on the Welsh coast. Close to the camera, an elderly woman lounges in the sun surrounded by things important to a seaside visit, while in the background we see beach-goers emerging from a ghostly veil of mist that hovers across the beach. I just cannot imagine this photograph having the same visual impact or quality in colour, can you?

Banner image: Herne Bay, Kent © David Hurn/Magnum Photos

The Great British Seaside: Photography from the 1960s to the present

From the abandoned piers to the dazzling arcades, celebrate the British seaside through the lenses of Britain’s most popular photographers, featuring Tony Ray-Jones, David Hurn and Simon Roberts and new work by Martin Parr.