Discover some of the surprising entries recently discovered in the medical records of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital. Are you able to join our transcription project and help to unearth more?

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich was the main clinical site of the Seamen’s Hospital Society (now Seafarer’s Hospital Society), founded to bring relief to sick and injured seafarers of all nations. The HMS NHS: The Nautical Health Service project was launched in 2021 to transcribe the many thousands of entries in the hospital admission registers between 1826 and 1930. The amazing work of the HMS NHS volunteers will provide researchers with opportunities to explore more than one hundred years of medical care provided at the centre of maritime Greenwich.

There’s still time to join the project. Click here to find out more, or read on to hear just some of the latest discoveries made by volunteers.

This blog explores records of boys and apprentices, the latter indicated in the admission registers by the abbreviation ‘app’ or similar. Boys often qualified for medical treatment at the Dreadnought on account of their being junior members of the seafaring occupational group. Several interesting stories and queries relating to young seafarers have arisen during the HMS NHS project.

Boys from training and reformatory ships

A good percentage of boys came to the Dreadnought from static training and reformatory ships on the River Thames. The confined sleeping quarters on these vessels encouraged the spread of infectious diseases, while seamanship training inevitably resulted in accidents and injuries. As featured in our blog from last year, one of our volunteers discovered a group of 72 boys from the school ship Goliath admitted for ophthalmia (inflammation of the eye) on 14 October 1872. The Goliath was moored off Grays in Essex and run by the Forest Gate School District. An outbreak of a different kind occurred on the reformatory ship Cornwall, nearby at Purfleet, run by the London School Ship Society. There were 15 boys from the Cornwall admitted with typhoid (or enteric) fever on 6 October 1875. Many cases of scarlet fever, which typically affects groups of children, can also be found in the registers.

A photograph of Robert Samuel Nodes as a Marine Society boy on the training ship Warspite, c.1904 (RMG reference MSS/85/119).

The idea of vocational training for boys destined for sea service took hold during the nineteenth century and a floating establishment was seen as the best basis of this. Frank Thomas Bullen (1857-1915) wrote from personal experience in his book The Men of the Merchant Service, published in 1900, explaining that there was a stark contrast between the disciplined character of life on training ships and the more anarchic rules at sea. Among the crew of a working vessel, a boy was at everybody’s beck and call, and could suffer from harsh treatment. Many of the opportunities for boys were in the demanding coastal trades, on outdated sailing vessels which had a precarious economic existence.

Apprentices at sea

From 1824 onwards, British merchant ships over 80 tons were legally required to carry a quota of indentured apprentices. As part of the enforcement of the regulations, records of indentures were kept by local Custom officers and the Registry of Shipping and Seamen in London. After the compulsory system was abolished in 1849, records of apprentices continued to be maintained. Entries of teenage boys in the Dreadnought registers can therefore sometimes be cross-referenced with indexes to the surviving registers of apprentices in the BT 150 series at The National Archives (TNA), partly accessible via the Ancestry website.

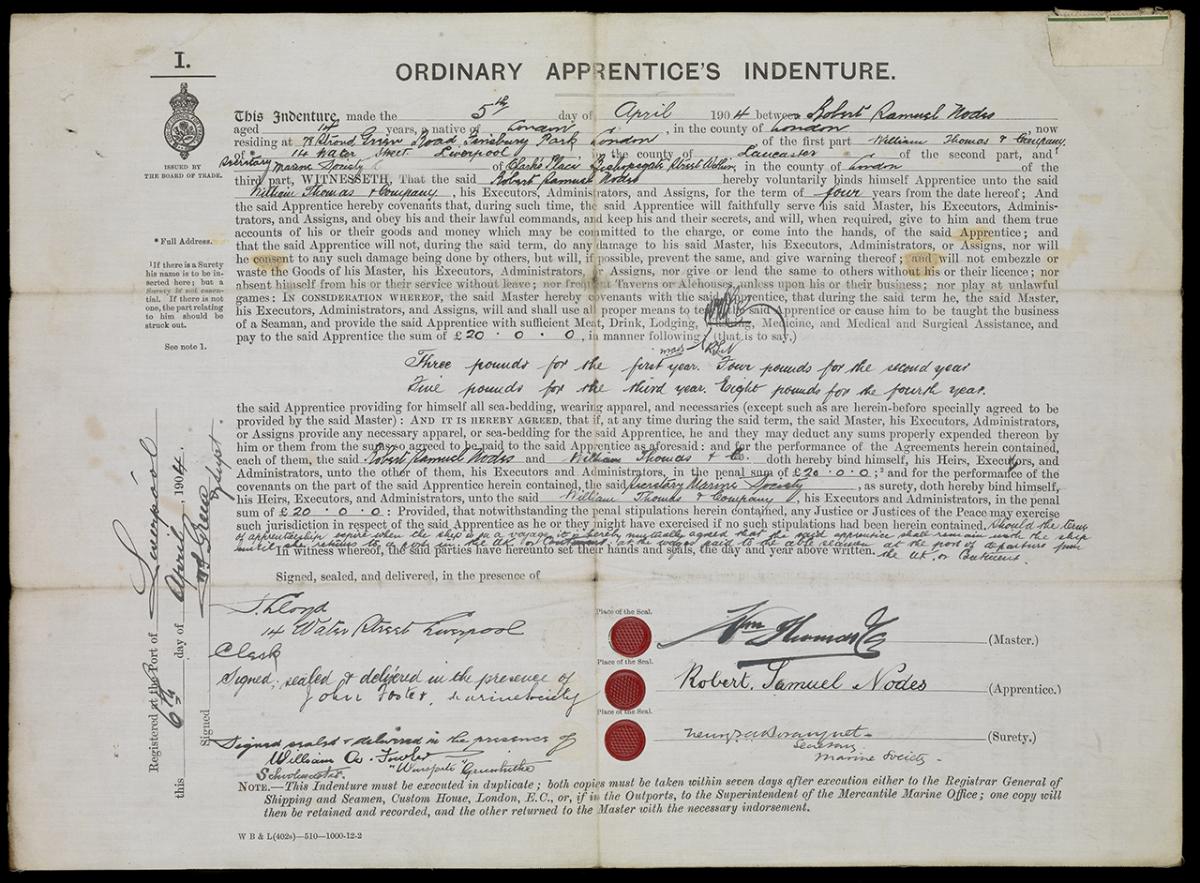

Apprenticeship indenture of Robert Samuel Nodes, 1904 (RMG reference: MSS/85/119).

Boys from workhouses or reformatory ships were often bound as an apprentice to a ship’s master to deter them from falling into unemployment, possibly followed by criminality or destitution. Such was the situation of the orphan Oliver Twist in Charles Dickens' novel of the same name, first published in 1838. Early in the story, the workhouse officials consider the expediency of shipping Oliver off in a merchant vessel. Despite the likelihood of him coming to physical harm at the hands of a violent skipper, Mr Bumble believes this to be the only effective way of providing for him. Many thousands of impoverished boys from the London area were recruited via The Marine Society’s training ship Warspite on the River Thames. The Marine Society registers of apprentices sent to merchant ships can be found in the MSY/Q series held at Royal Museums Greenwich.

In the Dreadnought records we can find Cuthbert Stevenson (or Stephenson), aged 14, born in Sunderland, admitted with an inflamed leg on 22 March 1862. This was just one week after going to sea on the brig Humility (1853) of Sunderland, which regularly carried coal to London. A half-yearly crew agreement for the Humility confirms that Stevenson had been engaged as a boy ‘on trial’. The relevant BT 150 records tell us that two years later he was indentured for a term of four years on the brig Tartar of Sunderland, also in the coal trade. He reappears in the Dreadnought registers as an able seaman, aged 20, admitted with fever on 2 July 1867.

Family history resources suggest that Stevenson was born in Monkwearmouth in 1850, so may have been only 12 when he first came for treatment at Greenwich. During the era of sailing ships, it was common for boys to go to sea at such an age. This situation changed with elementary education acts which raised the school leaving age, and increased restrictions on child labour. An official publication The Employment of Boys in The Mercantile Marine from 1916 outlines a variety of entry-level roles for boys aged 14 upwards. However, it was advised that they should be at least 15 before going to sea. Boys from more privileged backgrounds had the option of officer training on a fee-paying basis on HMS Worcester (Thames Nautical Training College) at Greenhithe. Two years as a cadet on the Worcester counted for one year of sea service in applications for sitting Board of Trade examinations.

Pages from a discharge book recording voyages made by Edwin Lanceley Davies as a deck boy and cadet, 1908-1912 (RMG reference MSS/86/093).

Boys among the shore casualties

Following the move of the Dreadnought to its shore location in 1870, increasing numbers of ‘landsfolk’ were admitted in the context of local accidents and emergencies. From the 1890s onwards, press notices appealing for funds to support the humanitarian work of the Seamen’s Hospital Society highlighted the admission of women and children of both sexes.

Some of the boys admitted to the Dreadnought were connected with industries allied to the port of London, such as the shipyards and marine engineering workshops. An example is John Hammersley, aged 12, admitted with a fractured radius on 10 August 1861. He was employed as a rivet boy with the iron shipbuilding firm of Charles Lungley & Co. at Deptford.

For further reading on apprenticeships at sea in the nineteenth century see Apprenticeship Regulation and Maritime Labour in the Nineteenth Century British Merchant Marine by V.C. Burton, in ‘International Journal of Maritime History’, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1989, pp.29-49.

The above stories were discovered, researched and shared by HMS NHS volunteers, often via the project’s discussion boards. As well as the place to ask transcription questions, it’s also a great place to share interesting discoveries made in the records.

We’d love to hear from you if you have some time to spare to help this project along!