Learn about the life of the pioneering mathematician, astronomer and polymath – and his links with the Royal Observatory

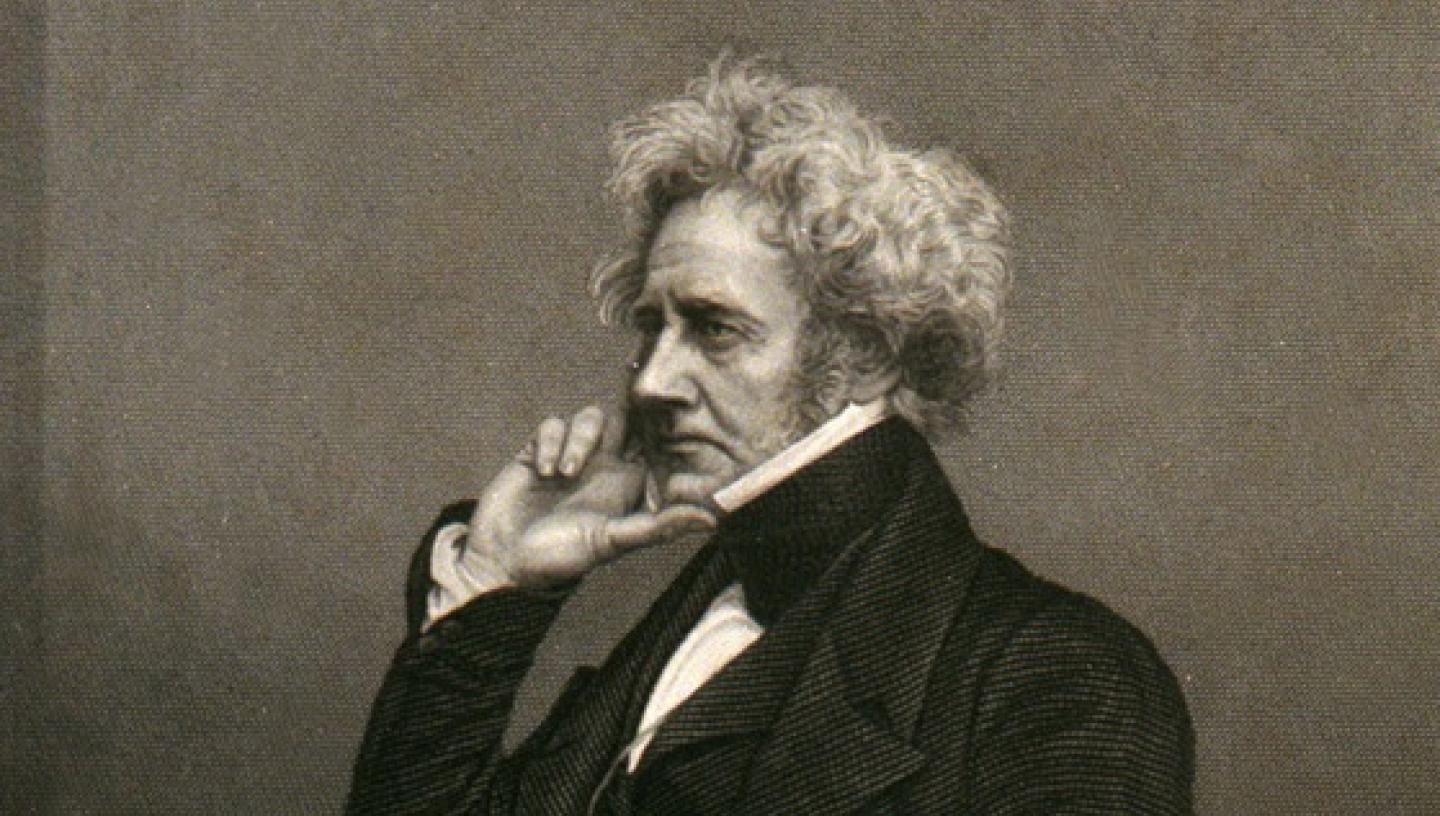

This month is the 150th anniversary of the death of Sir John Frederick William Herschel, who not only continued his father’s astronomical work but also made a name for himself in mathematics, chemistry, photography, geology and meteorology. He was a close acquaintance of the seventh Astronomer Royal, George Biddell Airy (1801–1892) and was involved in many common projects that shaped the work of the Royal Observatory during the first half of the 19th century.

We have a fantastic collection of items relating to the Herschel family, let’s take a closer look to explore John Herschel’s story.

‘[The stars are] the same for ever and in all places, of a delicacy so extreme as to be a test for every instrument yet invented by man…’

John Herschel, ‘An Address delivered …’, Philosophical Magazine, vol 2, pp. 456–7 (1827)

Cambridge mathematics

Born on 7 March 1792 at Observatory House, Slough, John Herschel was the only child of William and Mary Herschel. His childhood was an eclectic mix of local schooling and private tuition, especially in mathematics at which he excelled. His famous comet-hunting aunt, Caroline Herschel (1750–1848), lived nearby and the pair remained close throughout their lives. The young scholar subsequently enrolled at St John’s College, Cambridge, and finished as Senior Wrangler (best mathematics student) in 1813.

This was an exciting but controversial time to study mathematics at Cambridge. Along with his fellow students Charles Babbage and George Peacock, he became a founder member of the Analytical Society whose aim was to convince Cambridge scholars to adopt innovative mathematical techniques that were emerging in Europe. Over the next few years, Herschel and his peers translated relevant texts from French to English and managed to add the new content to examination papers. Peacock was particularly influential in persuading the University to establish a new observatory that would serve as the training ground for Herschel’s friend, George Biddell Airy, who would become the next Astronomer Royal in 1835.

Learn more about the position of Astronomer Royal

Astronomical technology and observations

After graduation, Herschel spent a few years exploring ideas in chemistry and mathematics before deciding to continue with his father’s programme of astronomical observations. In 1820 the father-son duo team reconstructed William’s favourite telescope, the 20-foot (focal length) reflector, with a stronger supporting frame and better optics that relied on a polished metal mirror. With this improved design, William and John meticulously scanned the skies to create their catalogue of fuzzy patches known as ‘nebulae’ that later revolutionised our understanding of our galaxy, the Milky Way, and the structure of the Universe. After his father’s death in 1822, John continued to use the telescope to catalogue nebulae, star clusters and double stars, for which he received the Royal Astronomical Society’s gold award in 1826.

The 20-ft reflector telescope has survived within Royal Museums Greenwich’s collection (AST0950) and is currently on display in the ‘Explore the Universe’ gallery at the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum, Washington D.C., USA. To keep their observations systematic, William and John also used a machine with a bell (‘zone clock’) that rang whenever they moved the telescope away from the required area of sky.

Surveying the southern skies from Africa

On 13 November 1833, Herschel and his wife Margaret (née Brodie Stewart (1810–1884)) travelled on Mount Stewart Elphinstone to Cape Town to start a new programme of observing the southern skies. After a two-month journey at sea, Herschel installed the 20-ft reflector at Feldhausen, about five miles from the Royal Observatory at the Cape. Over the next four years he observed and catalogued over 1,700 nebulae, 2,000 double star systems and several comets. It was an incredibly productive period that made him the most experienced astronomer to have surveyed the skies visible from both the northern and southern hemispheres.

When he was not observing, Herschel took a keen interest in the geology, flora and fauna of the surrounding area by taking measurements and participating in local scientific societies. Herschel and his wife Margaret also created over 100 sketches of the local flora, along with picturesque scenes like PAH6036, shown here.

Chemical processes and photography

Herschel is also remembered for his contribution to chemistry, optics and photography. He was a keen advocate of the newly-invented camera lucida, patented by William Hyde Wollaston in 1806. Herschel used this portable projection device to view and sketch scenes of cathedrals, cityscapes and Roman ruins during his travels across Europe during the 1820s.

Nearly two decades later, Herschel became caught up in the excitement surrounding the new photographic processes created by Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) and Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877). He undertook various experiments on the light sensitivity of different materials to create the best chemical compounds for ‘fixing’ images onto glass photographic plates. He also created ‘cyanotypes’ or ‘blueprints’ for reproducing technical drawings; we have examples of such printing frames in our collection (AST1166). He was awarded a medal by the Royal Society for his contribution to photo-chemistry and his legacy endures as we continue to use his technical terms such as ‘positive’, ‘negative’ and ‘snap-shot’.

Check out our ‘Astronomy Photographer of the Year’ competition for inspirational images

Association with Greenwich

As a prominent man of science, Herschel was formally associated with the Royal Observatory as a member of the Board of Longitude and as a member of the ‘Visitors’ who were required to monitor the Observatory’s activities on an annual basis. He was a keen proponent of the newly-created ‘Magnetic and Meteorological Department’ that was formed in the late 1830s as Greenwich’s contribution to the global study of the Earth’s magnetic field.

On a less formal basis, Herschel and Airy were well-acquainted from their Cambridge days, with Herschel using his linguistic skills and international contacts to provide letters of introduction for the young Airy on his visits abroad. Airy also admired Herschel’s technical expertise, recording in his diary, ‘On Apr. 4th [1828] I visited Mr Herschel at Slough, where one evening I saw Saturn with his 20-foot telescope, the best view of it that I have ever had.’ [Airy’s ‘Autobiography’ p.82]

This friendship continued throughout their lives and extended across their families as well, with joint Christmas celebrations at Greenwich and the Herschels’ home in Kent, and many years of friendly and affectionate correspondence between their wives, Richarda and Margaret.