In this blog we look at a small volume packed with a plethora of facts and figures about the late Victorian River Thames compiled by Charles Dickens junior

Charles Culliford Boz (‘Charley’) Dickens (1837–1896) was the eldest child of the novelist and journalist Charles John Huffam Dickens and his wife Catherine Thomson Dickens (née Hogarth). He had a varied career, including banking and papermaking, before commencing work for his father’s magazine All the Year Round in 1868, eventually becoming its owner and editor. Charles Dickens also had a printing company, Dickens and Evans, with Frederick Moule Evans (his brother-in-law), and it was this company that published his guidebooks, including Dickens’s Dictionary of the Thames.

In his Preface to the 1892 edition, Dickens writes:

‘The objects aimed at in this book, which follows naturally on the original Dictionary of London [another of Dickens’s reference books], have been to give practical information to oarsmen, anglers, yachtsmen, and others directly interested in the river; to serve as a guide to the numerous strangers who annually visit the principal places on its banks; to furnish a book of reference for residents; as well as to provide in a concise form a useful handbook for those connected with the port of London and its trade.’

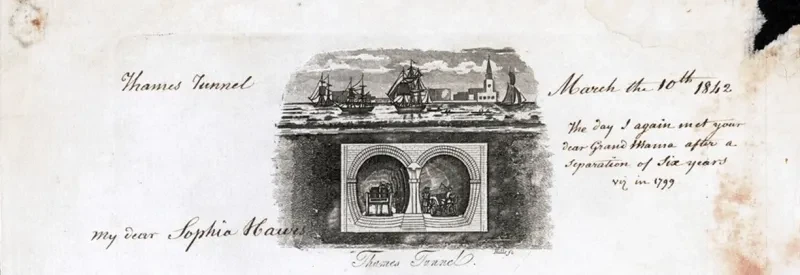

In short, the book was to be a fluvial miscellany of all sorts of information about the River Thames ‘from’, as the book’s subtitle says, ‘its source to the Nore’ (the Nore being the sandbank located where the Thames meets the sea).

An A to Z of the Thames

The book consists of a series of entries, arranged alphabetically from ‘Abingdon’ to ‘Yantlet Creek’. Among the entries under the ‘A’s’ is Angling Clubs, of which there were so large a number in London that the list stretches from page 9 to 12. Most give public houses or hotels as their locations: the Anerley Piscatorials at the Anerley Arms; the Funny Folks at the Rose and Crown in Goswell Road, Clerkenwell; the Odds and Evens at the Monmouth Arms in Haberdasher Street, Hoxton; the St John’s Wood at the Knight of St John’s in Queen’s Terrace; and The Trafalgar at the Star and Garter Hotel in St Martin’s Lane.

In terms of which fish were in the river, Dickens tells us that ‘Sturgeon occasionally come up the Thames, but they were never numerous in this river’ and that ‘Whitebait was formerly caught much higher up the Thames than at present. The principal area of supply is now between Woolwich and Gravesend, the legal season being April to September.’ As for salmon, ‘There may be more causes than one to which the entire absence of salmon from the Thames are attributable, but pollutions alone would sufficiently account for their absence.’

Under the entry for ‘swimming’ there are details of some of the winners of swimming races and also a list of swimming clubs, all but one of which ‘hold their principal race – the captaincy race – in the Thames’. The meetings, however, are usually at swimming baths.

The entries can be discursive or idiosyncratic. About barges, Dickens writes:

‘Although the extension of railway facilities in the country through which runs the Upper Thames has very considerably reduced the number of upriver barges, there are still many engaged in the carrying trade. That they are useful, may be taken for granted; that they are possibly ornamental, may be a matter of opinion; that they are a decided nuisance when a string of them, under the convoy of a vicious steam-tug, monopolises a lock for an hour or so, admits of no doubt. And the steam-tugs themselves are an abomination. They are driven along with a sublime disregard of the interests of persons in punts and small boats […] and raise a wash which can be as little beneficial to the banks of the river as it is to the peace of mind of anglers and oarsmen.’

Meanwhile, on the lower river:

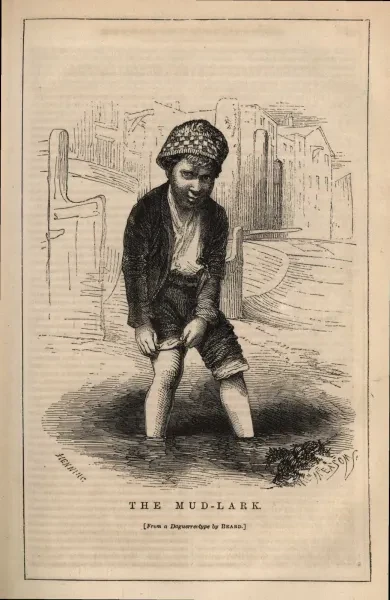

‘from about Brentford downwards that is – the barges occupy a very different position; an immense amount of the enormous goods traffic of the Port of London being distributed by their medium, and their numbers appearing to be steadily on the increase. They are of two kinds, sailing and dumb barges. These latter are propelled by oars alone, and drift up and down apparently at the mercy of the tide. […] They are quite incapable of getting out of the way, or of keeping any definite course, and as they bump about among the shipping and get across the bows of steamers, they are the very type of blundering obstructiveness, and an excellent example of how time is allowed to be wasted in this country.’

Bridges and buoys

There is also idiosyncrasy in the entry for Westminster Bridge:

‘Westminster Bridge varies very much in appearance with the state of the tide. It is always a rather cardboardy-looking affair, but when the river is full, and the height of the structure reduced as much as possible, there is a certain grace about it. When, however, the water is low, and the flat arches are exposed at the full height of their long, lanky piers, the effect is almost mean. Except, however, for the excessive vibration arising from lightness of construction, it is one of the best, from a practical point of view, in London, the roadway being wide and the rise very slight.’

There is also a list of bridges, divided under two headings, ‘CRICKLADE TO OXFORD’ and ‘OXFORD TO PUTNEY’. This gives bridges’ names, notes if they are footbridges, and gives their distances from the two place names in the respective headings. There is also a list of buoys managed by Trinity House, and these also have their own individual entries which give more detail. The Ovens Buoy, for example, is described as ‘A 20-foot conical buoy, made of iron, and painted black. It is situated in Gravesend Reach, three miles below Gravesend, at the edge of the Oven Spit on the Essex (left) bank, and marks a depth of water, at low-water spring tide, of 9 feet. It is moored with 15 fathoms of chain.’

Gravesend is also the location of the Pilot Station, which Dickens tells us:

‘is the chief rendezvous of all the various classes of men licensed to conduct ships into and out of the River Thames. This station represents the point of division between the functions of river and sea pilotage. The outward-bounder, after being brought from the docks under the care of a river-licensed man, lands him, and comes under the charge of a man whose license qualifies him to take her to sea.’

The fares of watermen – who transported passengers on the Thames – can be found in the entry for ‘Watermen’s Fares’. A trip from Waterloo Bridge to Westminster Bridge, for example, cost 6d. for oars or 3d. for a sculler, while the fare from below London Bridge to Crawley’s Wharf at Greenwich cost 5s. by oar or 2s. 6d. by sculler. (A scull is a lighter oar, for use by one person.) ‘The above fares,’ we are told ‘in all cases to include passengers’ luggage, not exceeding 56 lbs. for each person. All luggage above that weight to be paid for at or after the rate of 4d. for each 56 lbs.’

Beyond the river's banks

The book includes advertisements (some illustrated) at the front and back, which provide other glimpses into the fashions and amusements of the age. Advertisements include ones for patent medicines and a full-page one for ‘EPPING FOREST, LONDON’S GREAT HEALTH RESORT, Only Half-an-Hour from the City’. […] There are special attractions in the Forest during all seasons of the year. Nightingale and other birds abound.’ For men’s and boys’ clothing of the time, there is a multi-page advertisement for Chas. Baker & Co’s Stores Limited with illustrations of the morning coats, frock coats and tweed suits on offer.

As well as an original copy of the 1892 edition (RMG ID: PBK0692), the Caird Library has modern facsimiles of the editions from 1887 (RMG ID: PBF3568) and 1893 (PBC6800). Charles Dickens also published guidebooks of London, Paris, Oxford and Cambridge (not available at the Caird Library).

The Caird Library & Archive

Header image: A royal visit to Greenwich Hospital by Frederick James Havell, William Havell, and J. Robins & Sons | National Maritime Museum Collection