Discover some of the surprising entries recently discovered in the medical records of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital.

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich was the main clinical site of the Seamen’s Hospital Society (now Seafarer’s Hospital Society), founded to bring relief to sick and injured seafarers of all nations. The HMS NHS: The Nautical Health Service project was launched in 2021 to transcribe the many thousands of entries in the hospital admission registers between 1826 and 1930. The amazing work of the HMS NHS volunteers will provide researchers with opportunities to explore more than one hundred years of medical care provided at the centre of maritime Greenwich.

A curious kind of button

Last month one of our volunteers found the note ‘removal of Murphy button’ entered in the 'nature of complaint' column. It was in relation to a patient named as Leonard Sutur, aged 24, a coal porter, of 14 Church Street, Greenwich. He was admitted to the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on 18 May 1914 and discharged in a relieved condition after a stay of twenty-three days. Birth and census records suggest that this individual was possibly Alfred Leonard Suter, born in Woolwich in 1887, who had been admitted to the hospital on two previous occasions.

A Murphy button, more formally known as an anastomosis button, was a metal device of two halves used as an artificial connection between severed parts of intestinal tissue. The button saved time in surgery and was intentionally left in place after the procedure. As the join healed, the button was supposed to be released and pass out of the patient by natural process. The note in the register suggests that Suter had undergone the surgical procedure, but in the intervening time, the button had not been released as intended, or had got stuck somewhere else in the bowel.

The anastomosis button was invented in 1892 by John Benjamin Murphy (1857-1916), an American surgeon who specialised in abdominal work and gained international acclaim. Various forms of artificial anastomosis are used in surgery today, including a plastic device similar to the Murphy button, used as part of the process of stapling bowel tissue together. In July 1914, the month following Suter’s discharge from the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, Murphy happened to be in London to give a presidential address at the fifth session of the Clinical Congress of Surgeons of North America, held at the Hotel Cecil.

Anastomosis button, London, England, 1925-1935. © Science Museum, London.

Psychiatric casualties of the First World War

Our last blog highlighted evidence of the various physical injuries suffered by military personnel who were brought to Greenwich by ambulance train during the First World War. The records from this period also give us some clues about the emotional repercussions of exposure to combat both on land and at sea. On numerous occasions during 1915, the term neurasthenia was entered in the 'nature of complaint' column. Neurasthenia was a term often used in preference to ‘shell shock’, but similarly applied to patients in a state of mental exhaustion or fatigue. The various symptoms included muscle pain, hysteria, depression, lack of appetite and insomnia. Looking at admission figures for the Royal Naval Hospital at Chatham alone, there were over 4,000 patients with psychological disorders between 1914 and 1918.

One example from the Dreadnought registers is Chief Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class William Elliot, admitted with neurasthenia on 17 October 1915 and discharged with improved health on 2 November 1915. Elliot had served on the troopship HMS Mars (1896) in the Dardanelles in September 1915 and had a home address at Gillingham in Kent. His official service record can be accessed via the Discovery catalogue on The National Archives (TNA) website, under the reference ADM 188/433/270320. It states that he was invalided with melancholia in March 1916, suggesting that he had a chronic condition. We don’t know whether this related to any particular trauma during his service at sea.

Melancholia was used in the earlier part of the twentieth century as a blanket term for various forms of depression. In the decades since, advances in psychiatry have of course enhanced our awareness and treatment of a range of more specific conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, clinical depression and bipolar disorder.

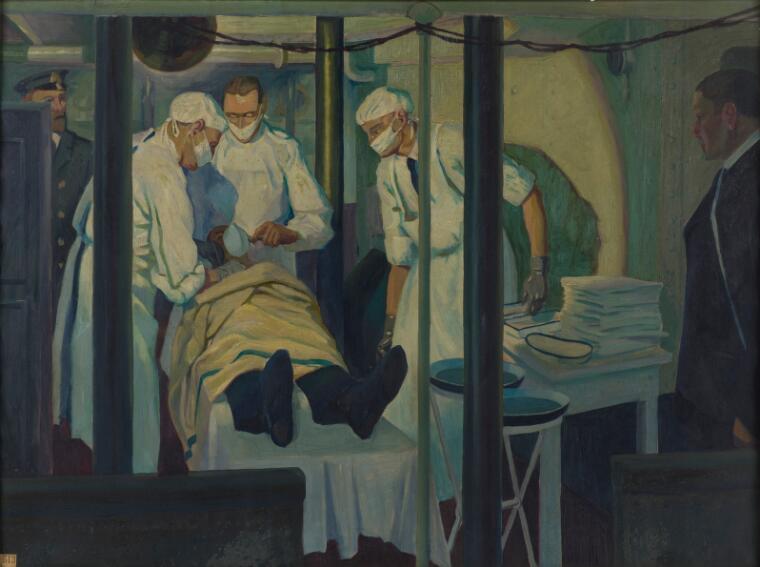

World War I: an operation in a light cruiser. Oil painting by Godfrey Jervis Gordon ("Jan Gordon") © Wellcome Collection

Miscreants in the neighbourhood

The abbreviation ‘SC’ regularly appears in the port of registration column of the admission registers from 1886 onwards. It was entered in circumstances when the individual wasn’t a seafarer or otherwise connected with the work of the port of London. One theory is that ‘SC’ is an abbreviation for ‘special case’, used to denote a deviation from the usual policy because it would have been inhumane to send this person to a hospital further away.

The ‘SC’ policy followed by the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital enabled medical treatment to be given to a great many unfortunate victims of accidents and illnesses in the Greenwich area. The policy was also extended to less savoury characters connected with criminal or anti-social behaviour. A famous example of this to be found in the admission registers is the anarchist bomber Martial Bourdin, aged 26, born in France, who died of fatal abdominal injuries following the premature explosion of his device in Greenwich Park on 15 February 1894.

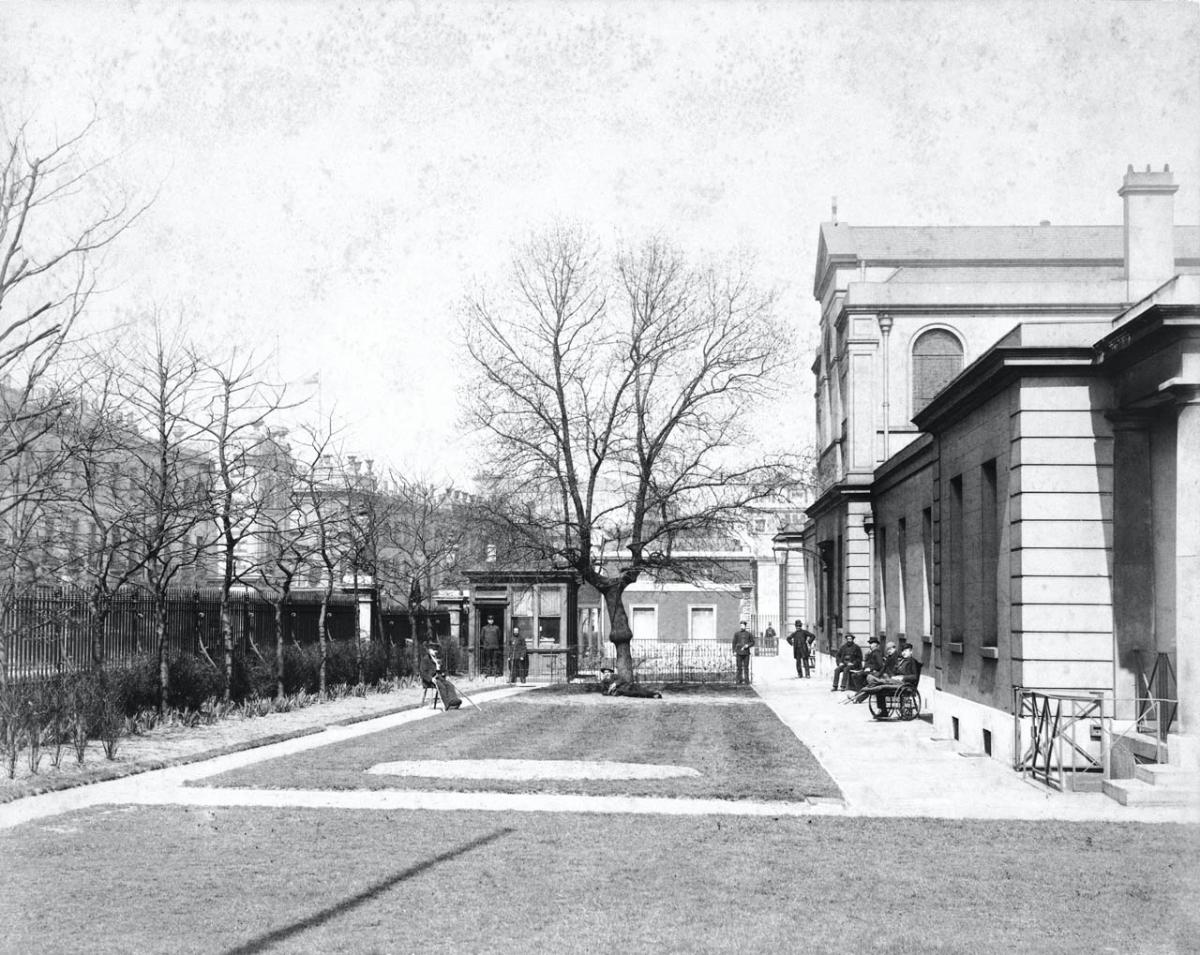

A photograph of the Somerset Wing of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, with King William Street on the left, circa 1900 (D3016-3)

Background stories of other miscreants admitted to the Dreadnought can be found in newspapers such as The Greenwich and Deptford Observer. One article tells us about a violent brawl in the Fubbs Yacht public house, in the waterfront area of Greenwich, on 26 December 1900. It resulted in two men, father and son, both named John Boswell and employed as coal porters, being admitted to the hospital with skull fractures. The landlord of the establishment, Arthur James Wormley, was charged by police with feloniously wounding and causing bodily harm to the pair. The Boswells denied that there had been any reason for Wormley to assault them in such a gruesome way. However, the hearing of evidence from witnesses resulted in the authorities being satisfied that Wormley was only trying to keep order in the public house and the charges against him were dismissed.

Another newspaper article tells us about a labourer named James Johnson, who was suspected of stealing and taken into police custody in the High Street at Deptford. He later got violent and attempted to escape, but one of his legs got fixed in the wheel of a costermonger’s barrow and was broken. The relevant register confirms that he was admitted to the Dreadnought with a fractured leg on 28 July 1890. He was allowed to have temporary sanctuary in the hospital, but a note states that he was ‘removed by police’ when discharged on 6 September 1890.

More information on the treatment of psychological disorders by the medical branch of the Royal Navy can be found in Royal Navy Psychiatry: Organization, Methods and Outcomes, 1900-1945 by Edgar Jones and Neil Greenberg, in ‘The Mariner’s Mirror’, Vol. 92, No. 2, May 2006, pp.190-203.