Discover some of the surprising entries discovered in the medical records of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital.

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich was the main clinical site of the Seamen’s Hospital Society (now Seafarer’s Hospital Society), founded to bring relief to sick and injured seafarers of all nations. The HMS NHS: The Nautical Health Service project was launched in 2021 to transcribe the many thousands of entries in the hospital admission registers between 1826 and 1930. The amazing work of the HMS NHS volunteers will provide researchers with opportunities to explore more than one hundred years of medical care provided at the centre of maritime Greenwich.

This blog explores several interesting stories about seafarers from the Indian Ocean region that have arisen during the HMS NHS project.

The employment of lascars

The unceasing flow of commercial shipping into the port of London during the nineteenth century naturally brought with it multitudes of visitors from different seafaring nations. Britain’s ownership of a large percentage of the world’s shipping tonnage meant that many of them had found employment on British-registered vessels.

Seafarers from the Indian subcontinent and surrounding regions were traditionally referred to as lascars. The term was often broadly applied, including seafarers who originated from more distant parts of Asia, such as the Malay peninsula and China.

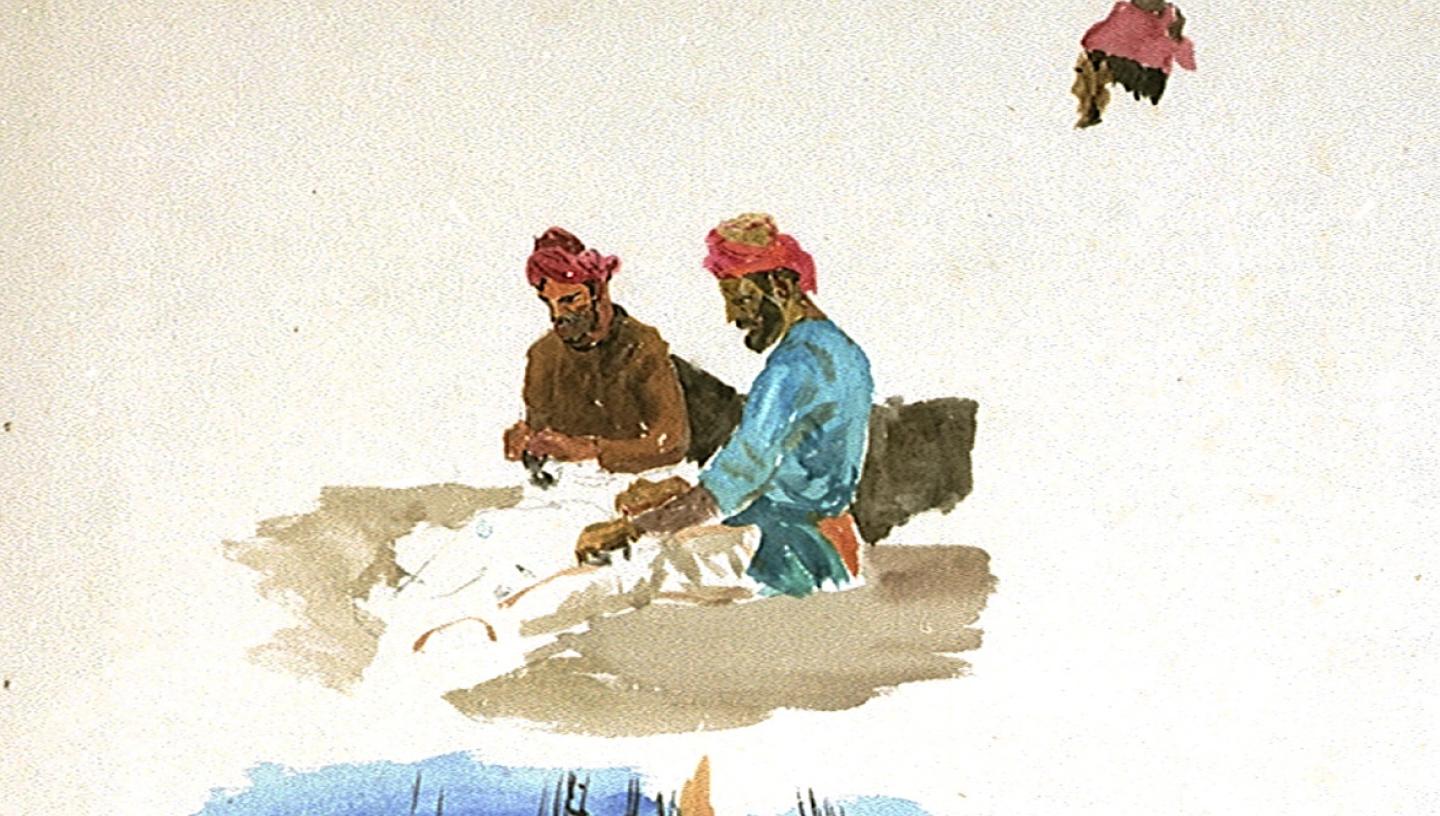

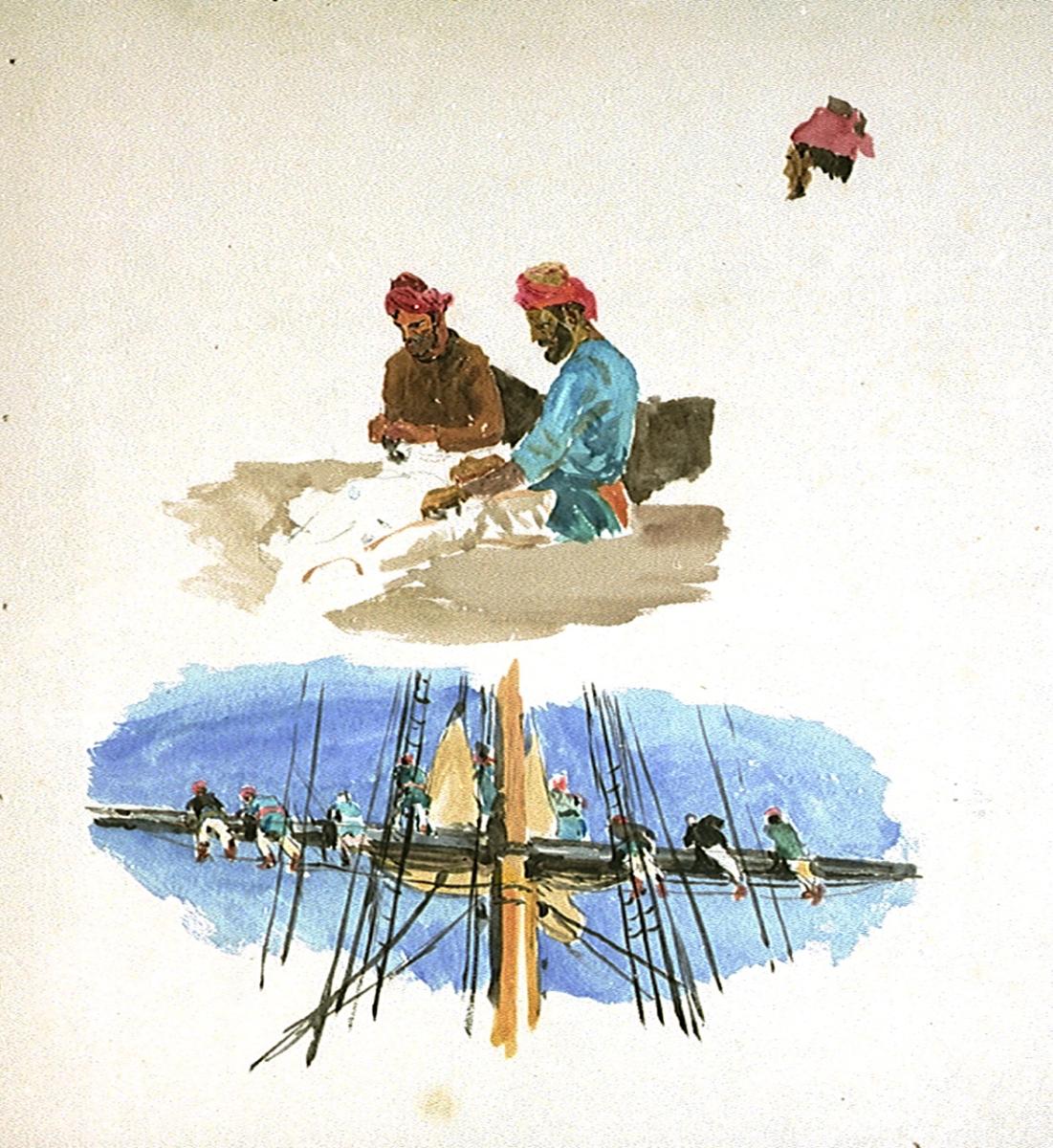

Lascar seamen manning yards by William Lionel Wyllie (PAE3062)

When they needed treatment for sickness or injury during their stay in London, all merchant seafarers, regardless of race or nationality, fell under the care of the Seamen’s Hospital Society. A numerical breakdown of the different nationalities recorded in its admission registers appeared in annual reports made by the governors. An early example from March 1826 stated that up to the end of the previous year, there had been 12 patients from the East Indian region out of a total of 4,679 admissions on board the Grampus hospital ship since its foundation.

While the Seamen’s Hospital Society publicised numbers of lascars admitted to the hospital to demonstrate the cosmopolitan and deserving character of the charity, British merchant shipping regulations and employment contacts enforced a system of discrimination.

Many lascars originated from parts of the British Empire and, through their work afloat, they contributed towards its prosperity. However, various shipping acts set them apart from the main body of British seafarers and their contracts were administered under separate Asiatic agreements. Above all, lascars represented a cheap method of filling gaps in crew numbers, as they were paid a fraction of the wages of their European counterparts. British shipowners were required by law to return lascars to their countries of origin, but they often neglected their responsibilities once ships had arrived in port.

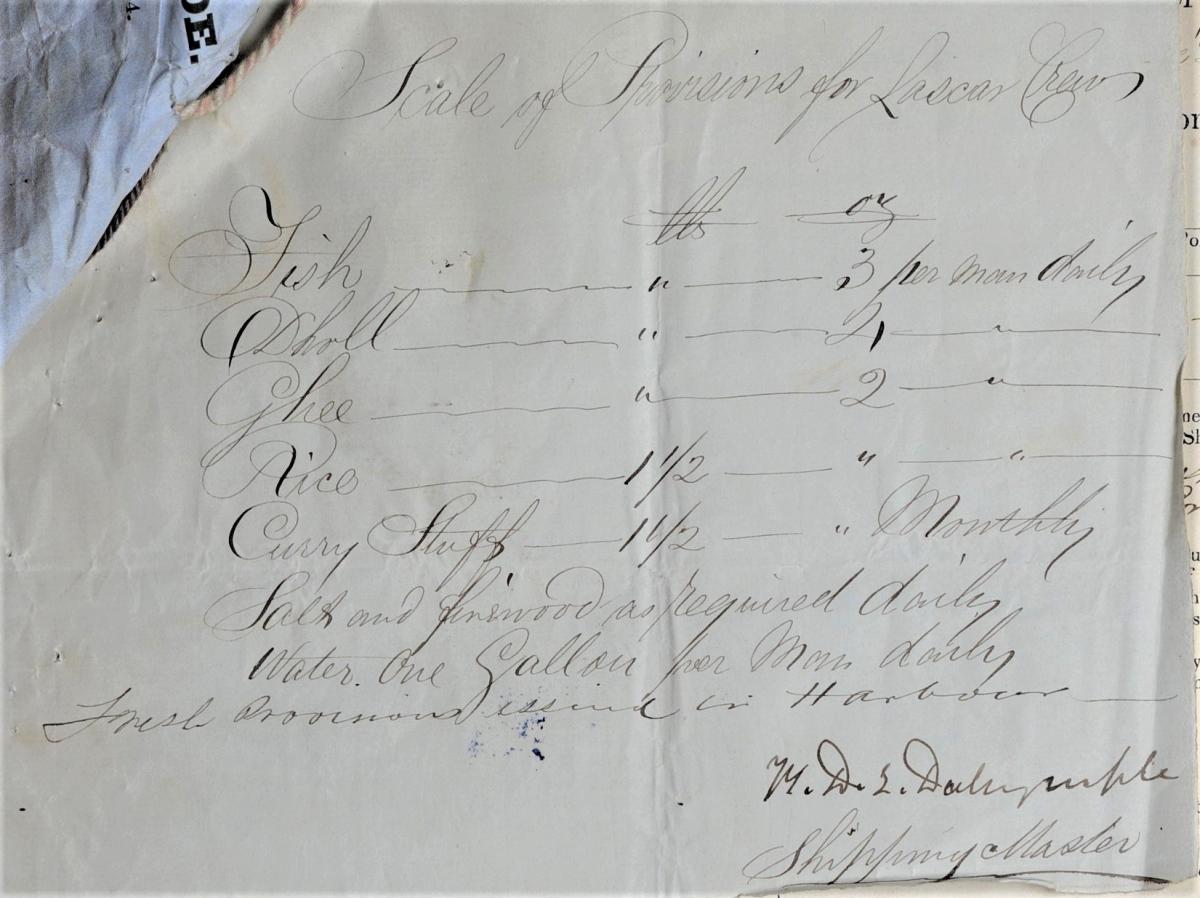

A scale of provisions for lascars employed on the barque David Malcolm (1839) in 1861 (RSS/CL/1861/14721)

The long periods lascars spent in inadequate living conditions, together with improper diet, accounted for their mortality rates from scurvy and other diseases being higher than those of other seafarers.

Lack of warm clothing and inexperience of harsh winter weather in the northern latitudes meant that they were more likely to suffer from pneumonia, frostbite and gangrene. Some of these issues were recognised in an essay on medical conditions commonly found among lascars on East India Company ships, written by the surgeon William Hunter in 1804.

Lascars in the Dreadnought registers

Evidence in the admission registers from the mid-nineteenth century suggests that living and working conditions for lascars largely remained unchanged.

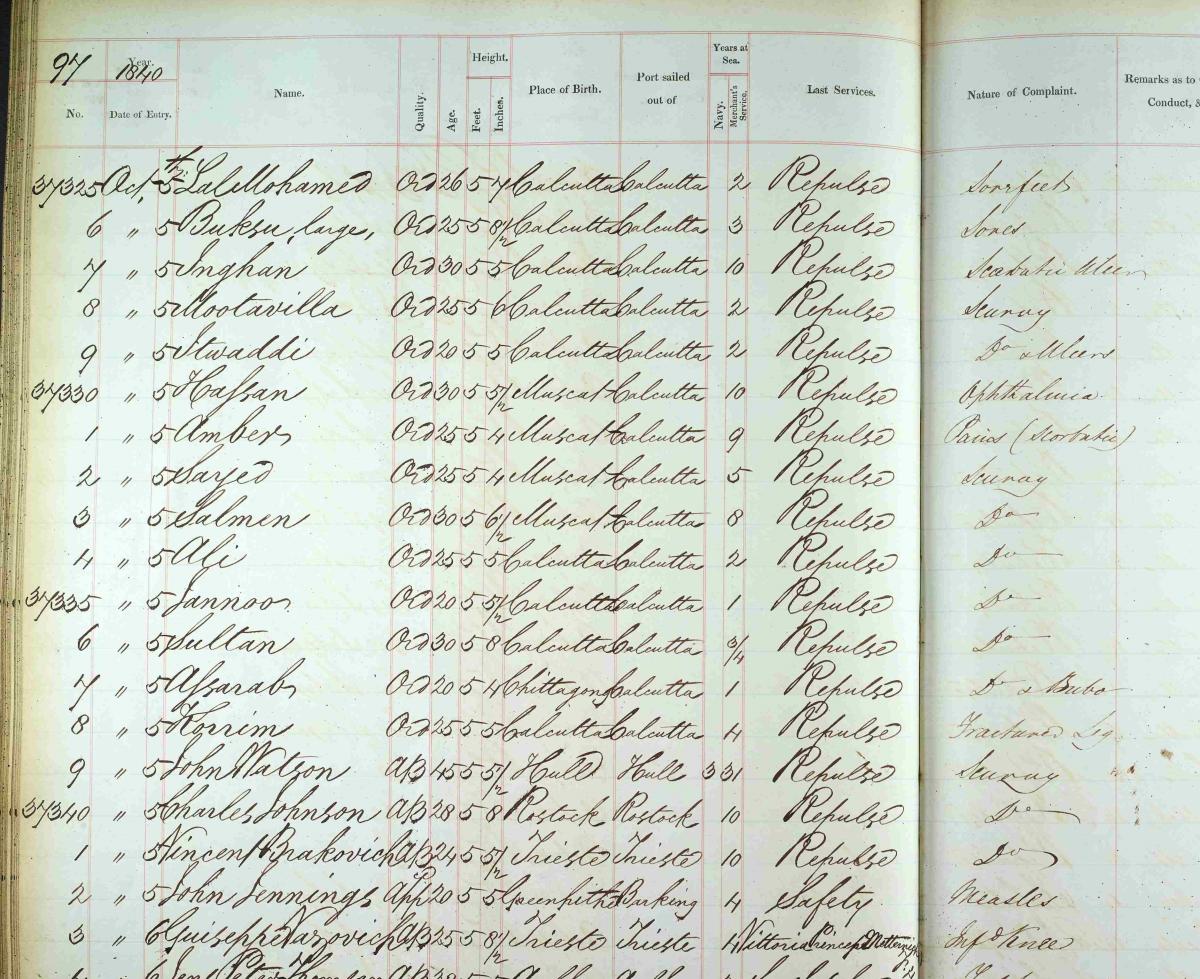

Some of the sailing ships sold at the termination of the East India Company’s trading charter in 1834 continued to be engaged in the India trade. They typically had crews mainly consisting of seafarers from regions of south and east Asia. An example is the Repulse (1820), which arrived in London from Calcutta (now Kolkata) early in October 1840. Twenty-five members of the crew, many suffering from scurvy, were admitted to the Dreadnought hospital ship on 5 October 1840.

Pages listing seafarers from the Repulse (1820) admitted to the Dreadnought hospital ship in 1840 (DSH/7)

Articles in the press comment on the destitute condition of the lascars, with their ragged clothes needing replacement. Three of them were recorded in the register with the single word name 'Buksu', illustrating the difficulties we would have in further researching these individuals.

Nineteen lascars from the Marlborough (1846), needing treatment for scurvy, frostbite and other complaints, were admitted to the Dreadnought on 3 October 1853. The Marlborough is an example of the faster sailing vessels, with the hull shape of a frigate, later used in the India trade.

There is an interesting background to the Malborough's arrival in London. The shipowners Thomas and William Smith of Newcastle had decided to take her off the India run to profit from the high passenger and freight rates associated with the Australian gold rush. Her eastward passage from Port Phillip to London began in early July 1853. Despite being hampered by a hurricane off Tasmania and having to steer clear of an iceberg in the Southern Ocean, the Marlborough reached Plymouth after an impressive run of just over 83 days. It was claimed to be the first time a ship with a lascar crew had rounded Cape Horn.

The Marlborough East Indiaman 1450 Tons (PAH0594)

Problems of destitution and repatriation

During the 1840s, press reports drew attention to an upsurge in numbers of lascars appearing destitute in London.

Often there were delays and disputes arising out of unpaid wages, or the inadequate accommodation provided for them in the port. Some deserted to escape from mistreatment and many wandered the streets, in danger of being cheated out of their possessions. This situation was partly addressed by legislation which obliged the East India Company (and from 1858 the India Office) to provide for and repatriate all seafarers from territories under its administrative control. It also required contracts relating to voyages from India to contain terms which bound lascars to later employment on ships returning to their homeland.

On the local front, lascars were given charitable support by various sailors’ homes and missionary societies.

Green’s Sailors’ Home in East India Dock Road, Poplar, established by the shipowner and philanthropist George Green (1767–1849), was in operation between 1841 and 1873. Lascars formed a significant percentage of the crews on ships owned by the partnership of Green and Wigram. Meanwhile, an appeal for the funding of a home for non-white seafarers led to the opening of the Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders in West India Dock Road, Limehouse, in 1857.

In the Dreadnought registers we can find a lascar named Toban Olla, recently employed as a greaser on the steamer Port Chalmers (1891), admitted in a destitute condition on 2 July 1894. A note records that he was sent to the Strangers’ Home. The establishment provided board and lodging for non-white seafarers at affordable rates and operated a shipping office to find them employment. It was also a centre for spreading the Christian gospel among seafarers. Contemporary accounts of such missionary work often use pejorative terms to describe the behaviour and beliefs of lascars and other seafarers from non-Christian cultures.

Lascars at the branch hospitals

Developments in steam power led to an increase in numbers of lascars engaged on British-registered ships, and they also accounted for a greater percentage of the workforce. Board of Trade annual statements tell us that lascars formed 10 per cent of the total workforce in 1891 and this had risen to 20.5 per cent by 1920.

Where there were shortfalls in available personnel, a range of deck, engine room, saloon and galley roles were deemed to be suitable for lascars. The stoking and trimming of coal were tasks typically assigned to seafarers who originated from hotter climates of the world.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, new schemes of enclosed docks were constructed downstream from Greenwich to accommodate large ocean-going cargo and passenger steamships. The mission of the Seamen’s Hospital Society could only be fulfilled by the establishment of facilities able to give prompt medical treatment to seafarers in the new dockland areas. When the Albert Dock Hospital branch became operational from 1890, a significant number of the patients were lascars employed on ships of the Peninsular & Oriental and British India Steam Navigation companies. Another development was a pavilion devoted to the treatment of lascars, named The Singhanee Ward. This was incorporated into building works when the Passmore Edwards Cottage Hospital at Tilbury was taken over from the East and West India Dock Company and redeveloped in 1924.

In the future, data from the HMS NHS project will provide new opportunities for studying patterns in the medical history and the working lives of lascars, and the ties these seafarers had with the establishment of Indian communities in Britain.

Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700-1947 by Rozina Visram, Pluto Press Limited, London, 1986.

Lascars, c.1850-1950: The Lives and Identities of Indian Seafarers in Imperial Britain and India by Ceri-Anne Fidler, PhD thesis, Cardiff University, 2011.

Lascars and Indian Ocean Seafaring, 1780-1860: Shipboard Life, Unrest and Mutiny by Aaron Jaffer, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2015.