Discover some of the surprising entries recently discovered in the medical records of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital.

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich was the main clinical site of the Seamen’s Hospital Society (now Seafarer’s Hospital Society), founded to bring relief to sick and injured seafarers of all nations.

The HMS NHS: The Nautical Health Service project was launched in 2021 to transcribe the many thousands of entries in the hospital admission registers between 1826 and 1930. The amazing work of the HMS NHS volunteers will provide researchers with opportunities to explore more than 100 years of medical records from the centre of maritime Greenwich.

Smallpox and the fate of the Dreadnought

Last year our volunteers discovered some examples of smallpox (variola) in admission registers from the 1850s. The policy of the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital was always to remove cases of this highly infectious disease. After diagnosis, patients were transferred as a matter of urgency; hence there are discharge details such as ‘sent to the smallpox hospital’ or ‘sent to SPH’.

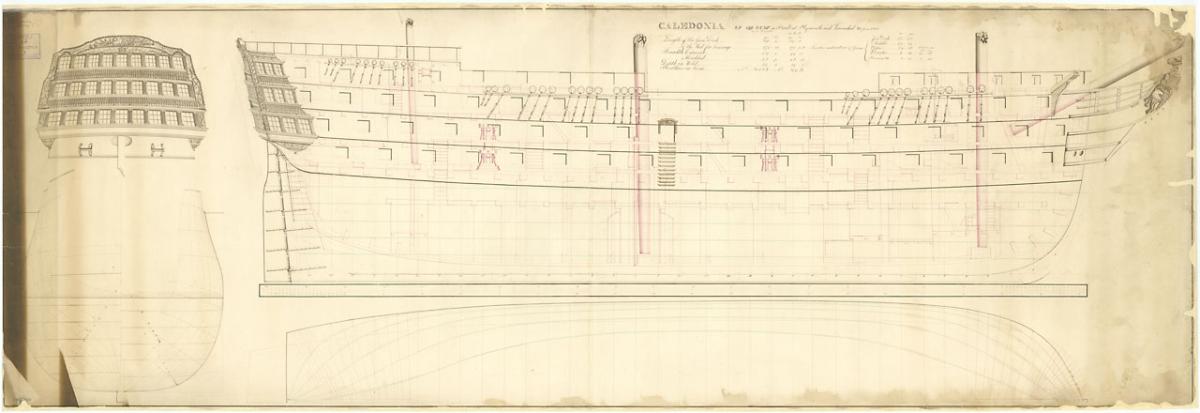

There was an outbreak of smallpox in London in 1871, the year after the hospital moved into the Infirmary and Somerset Ward of the Royal Hospital at Greenwich, leaving the Dreadnought empty. As one of the measures to address the epidemic, the ship was taken over by the Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB) and used as a floating convalescent hospital, off Deptford Creek. This final phase in the career of the Dreadnought, formerly the first-rate warship HMS Caledonia (1808), lasted between May and October 1871. The hulk was towed away from Greenwich in November 1872 to be broken up at Chatham.

Smallpox continued to be a threat, but widespread vaccination procedures and the use of isolation hospitals located away from the metropolis generally kept the disease at bay. Some individual cases can be found in later admission registers. For example, Simon C. Rusager, a Danish seaman employed on the cargo steamer Oceanic of Sunderland, was diagnosed with variola and ‘sent to fever hospital (smallpox ship)’ on 1 January 1897.

The Metropolitan Asylums Board used a trio of floating hulks as an isolation hospital in Long Reach, circa 1884-1903. Facilities for treating smallpox were later built on land nearby at Dartford. Meanwhile, inspectors of the Port Sanitary Authority were responsible for preventative measures on the waterfront. Vessels entering the port that were suspected of carrying contagious diseases, including smallpox, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever, were fumigated. Denton Isolation Hospital, sited downstream from Gravesend, was used for seafarers found to have infectious diseases.

The Wellcome Library provides online access to some relevant Medical Officer of Health reports for the Port of London from 1888 onwards.

Long-stay patients

There has been an informal contest among our volunteers to find the patient with the longest stay recorded in the registers, and a handful with over 1,000 days have been found.

The champion is Joseph Knox, a lighterman born circa 1788 at Dartford, who was admitted with rheumatism on 6 July 1841 and discharged dead on 15 January 1854: a total stay of 4,577 days, or almost 13 years.

The register states that he was employed on the working party, as a night watchman and frequently as a boatman. Why he was kept on the medical books all this time is unclear. His last place of abode given in the burial register of St Alfege at Greenwich is ‘Hospital Ship’, again suggesting that the ship was his home.

Another example of a long-stay patient is John Williams, born circa 1780 at South Petherton in Somerset. He was in the small group of naval veterans who, by special agreement between the Seamen’s Hospital Society and the Admiralty, remained as in-pensioners on the Greenwich Hospital site well after the Admiralty had vacated the buildings. When discharged dead on 6 January 1875, he had been victualled for 1,728 days.

First World War casualties and convalescents

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital was dedicated to the care of sick and injured merchant seafarers, but its remit widened during the First World War. It had to adapt to the extreme strains put on hospital capacity and shortages of trained medics. In the wider picture, the collaborative efforts of the Mercantile Marine and Royal Navy in wartime blurred the distinctions between civilian and military seafarers.

At the beginning of the conflict, arrangements were made so that the Dreadnought could offer 200 beds (out of a total of around 300) to Admiralty personnel. However, the first influx of combatants appearing in the admission registers was formed of soldiers from various army battalions on the Western Front. Nine of these casualties were admitted on 28 April 1915 and a much larger group of 100 came on 6 May 1915. Among the latter were several victims of gas poisoning belonging to 7th Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders and 48th Highlanders of Canada. These units were engaged around Ypres in Belgium, where the first major poison gas attack of the First World War took place on 22 April 1915.

Large numbers of Admiralty personnel from the Dardanelles campaign were received from 14 July 1915 onwards. Many had gun shot and shrapnel wounds, but dysentery and diarrhoea also frequently appear, both being common in the squalor of the trenches. Later in the year, on 21 September 1915, King George V and Queen Mary visited casualties of the Royal Naval Division and Royal Marine Light Infantry in the wards at Greenwich.

Some of the war casualties leaving the hospital had to convalesce before they were able to return to active duty. Discharge details in the registers have some intriguing references to convalescent homes, among them Sanderstead Court near Croydon. This was the estate of Edward Donald Morton, a wealthy export merchant, and his wife Emily Louisa Morton. We therefore also find records of patients sent to ‘Mrs Morton’s’. References to Sanderstead continue up to 1918, by which time the Angas Convalescent Home at Cudham was up and running. Some information on Cudham appeared in an earlier Museum blog.

Edward Donald Morton was one of two sons who inherited the C. & E. Morton Ltd. company, manufacturers of preserved and canned foods, which had factory premises at Millwall, Lowestoft and Aberdeen. It would be interesting to find out more about the link between the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital and the Mortons of Sanderstead.