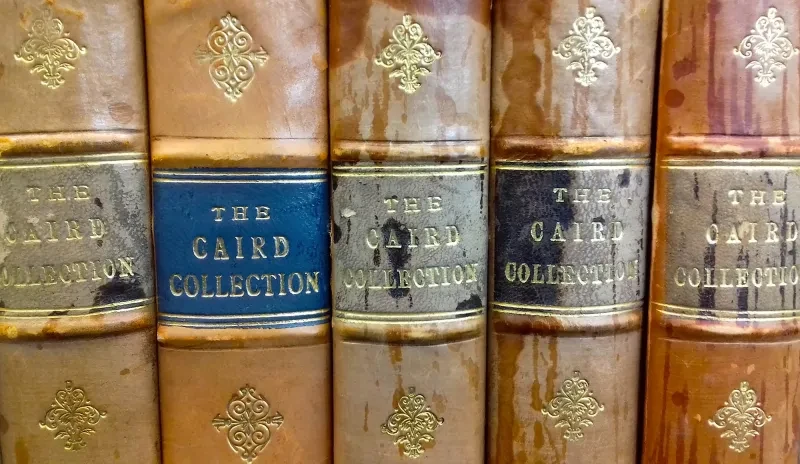

Explore a fascinating collection in the Caird Library and Archive which was written by a “traveller” who didn’t do any travelling.

The Caird Library and Archive is home to thousands of items documenting genuine, long-distance, eyewitness, round-the-world travels. My challenge in this blog, then, is to convince you that some of the most interesting volumes in the collection are in fact travel books written by a “traveller” who didn’t do any travelling at all.

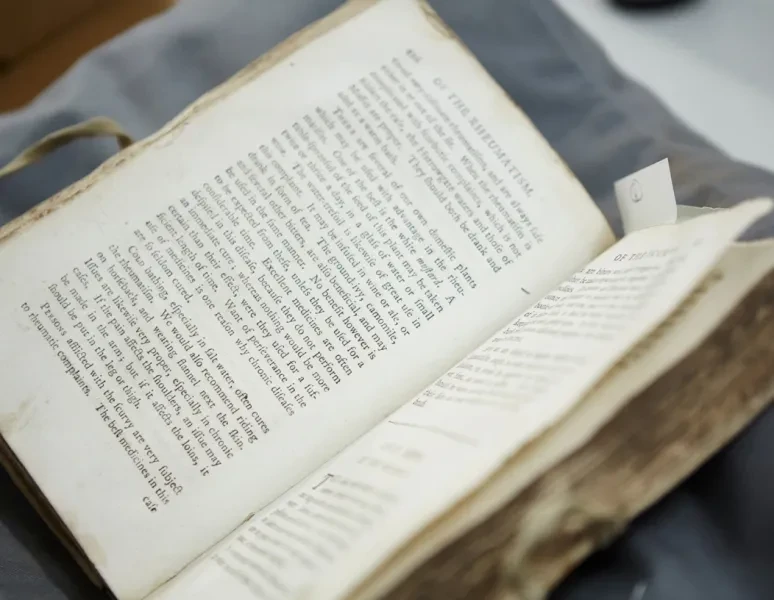

The author in question, Welsh naturalist and tourist Thomas Pennant (1726–1798), was by no means a lifelong homebody. His tours of Scotland and Wales, published in the 1770s and ‘80s, were based on extensive travels in those countries, and helped establish the “domestic tour” as a fashionable pastime in eighteenth-century Britain. The 'Outlines of the Globe' or 'Imaginary World Tour' (RMG ID: P/16/1–25) however, was his retirement project, written (as he details below, in his Literary Life) after his more ‘active’ existence had come to an end:

Thus far has passed my active life, even till the present year 1792, in which I have advanced half way of my 67th year…but my mind still retains its powers, its longing after improvements… A few years ago I grew fond of imaginary tours, and determined on one to climes more suited to my years… I determined on a voyage … along the oceanic shores of Europe, Africa, and Asia, till I have attained those of New Guinea…. The reader may smile at the greatness of the plan, and my boldness at attempting it at so late a period of life. I am vain enough to think that the success is my vindication.

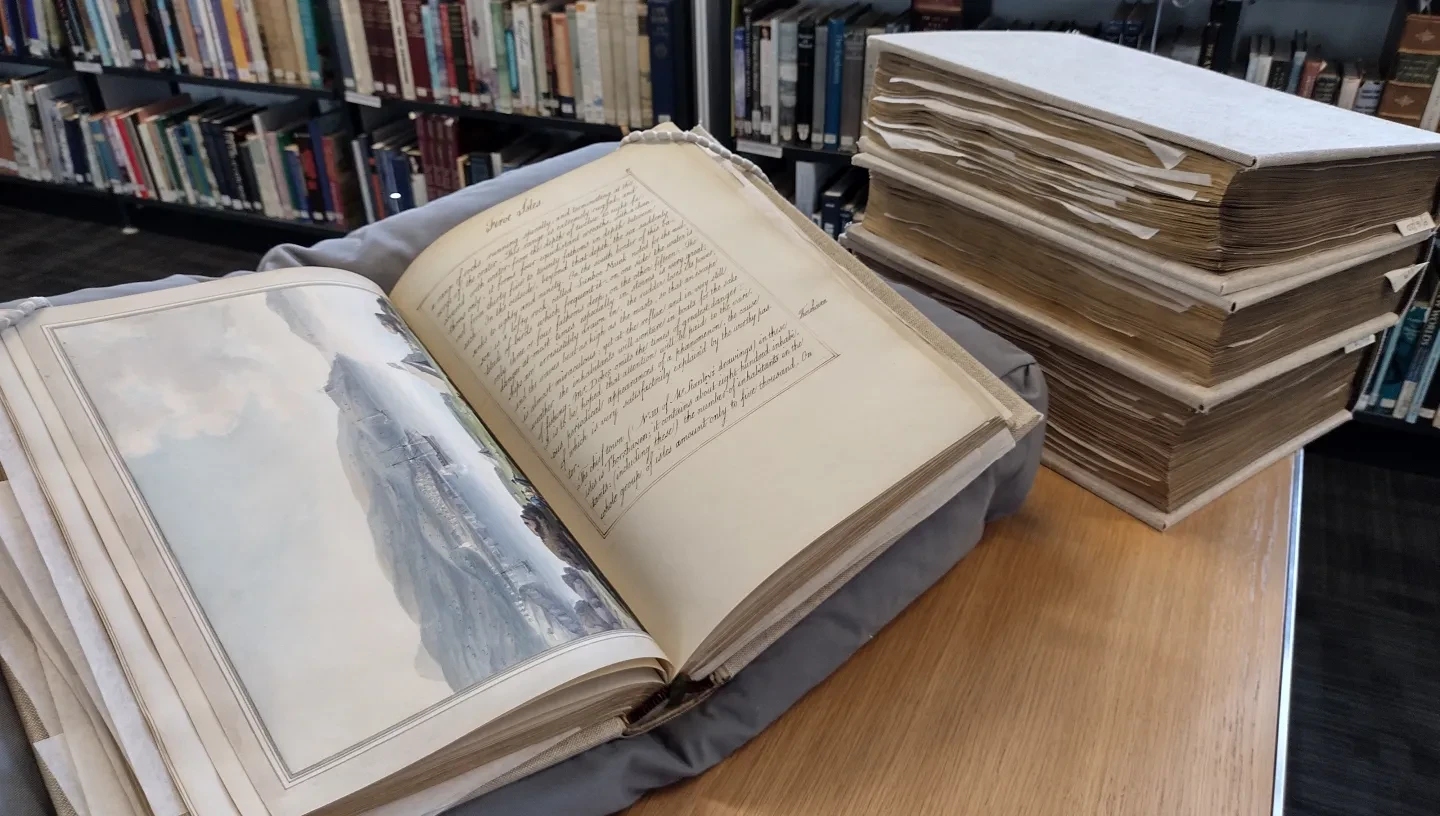

The 21 manuscript volumes of the ‘Outlines’ held at Greenwich, which I have been re-cataloguing as a Caird Fellow, represent the ‘vindication’ of Pennant’s plans for imaginary touring. In some cases (e.g. in volumes dealing with Britain, France, and Spain) they do contain information from real and recent journeys involving Pennant or his son David. In most cases, however, they are unrelated to the direct experiences of Pennant or his family, instead relying on the contents of Pennant’s library, the work of his employees and collaborators (including his personal artist Moses Griffith), and the images and knowledge he could gather from a wide network of friends and informants. As Pennant himself put it (again in the Literary Life):

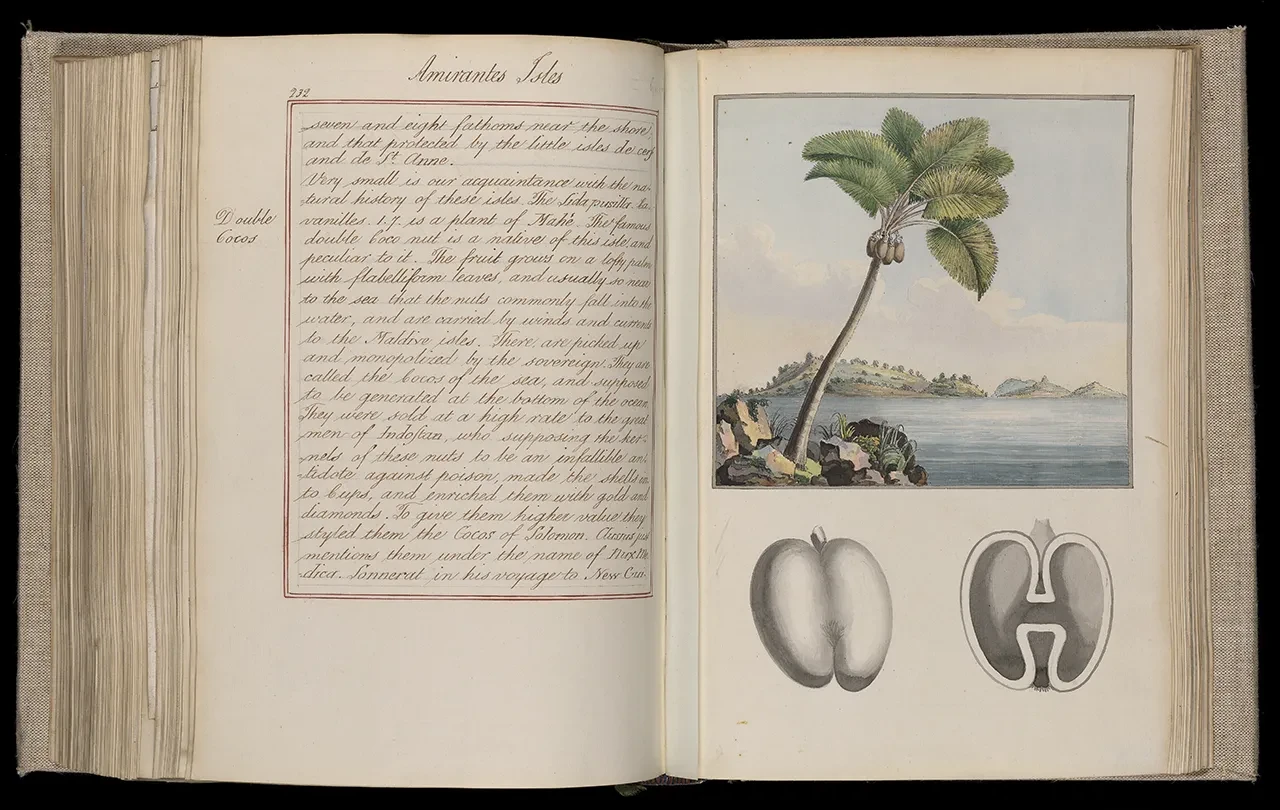

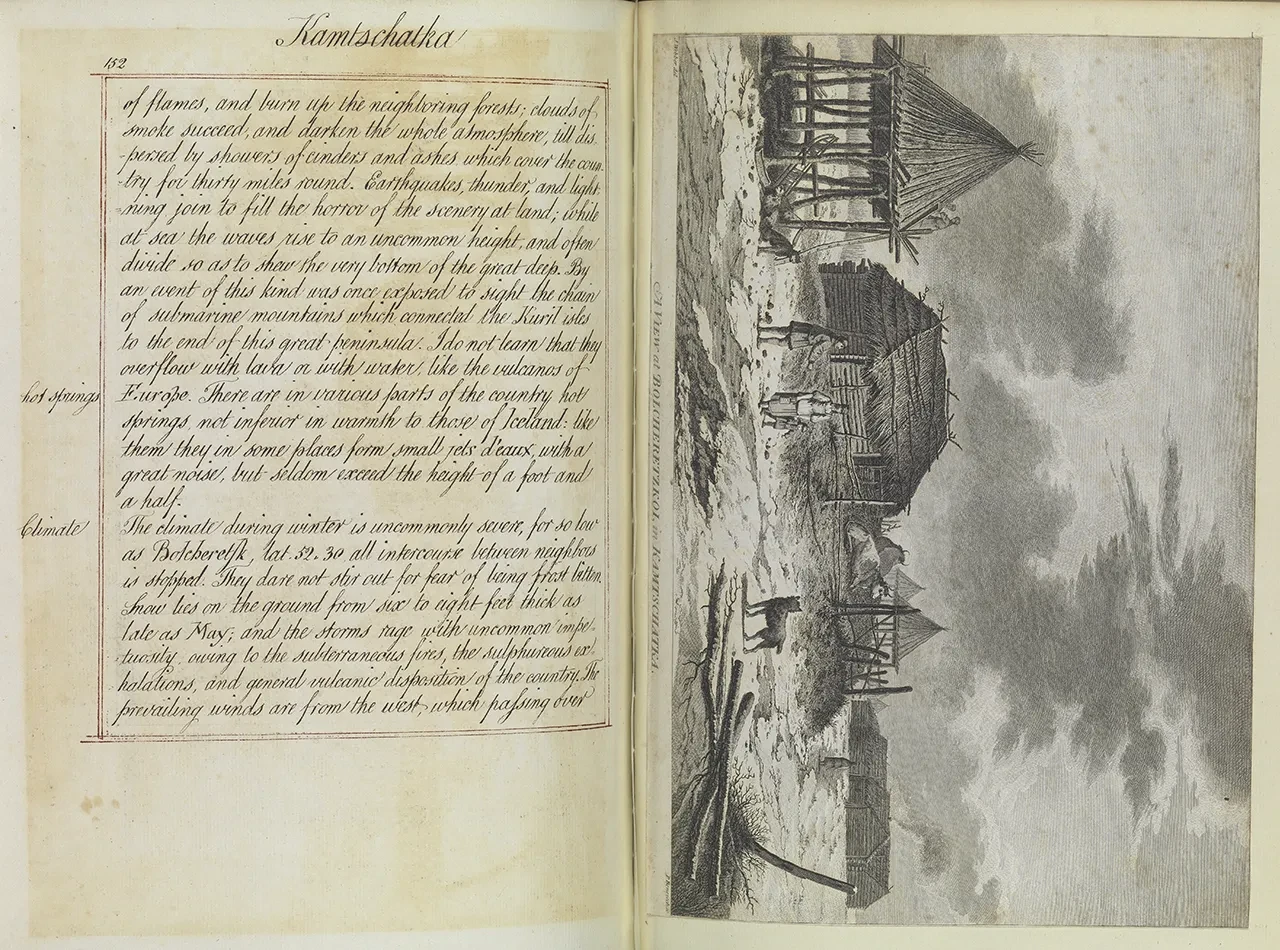

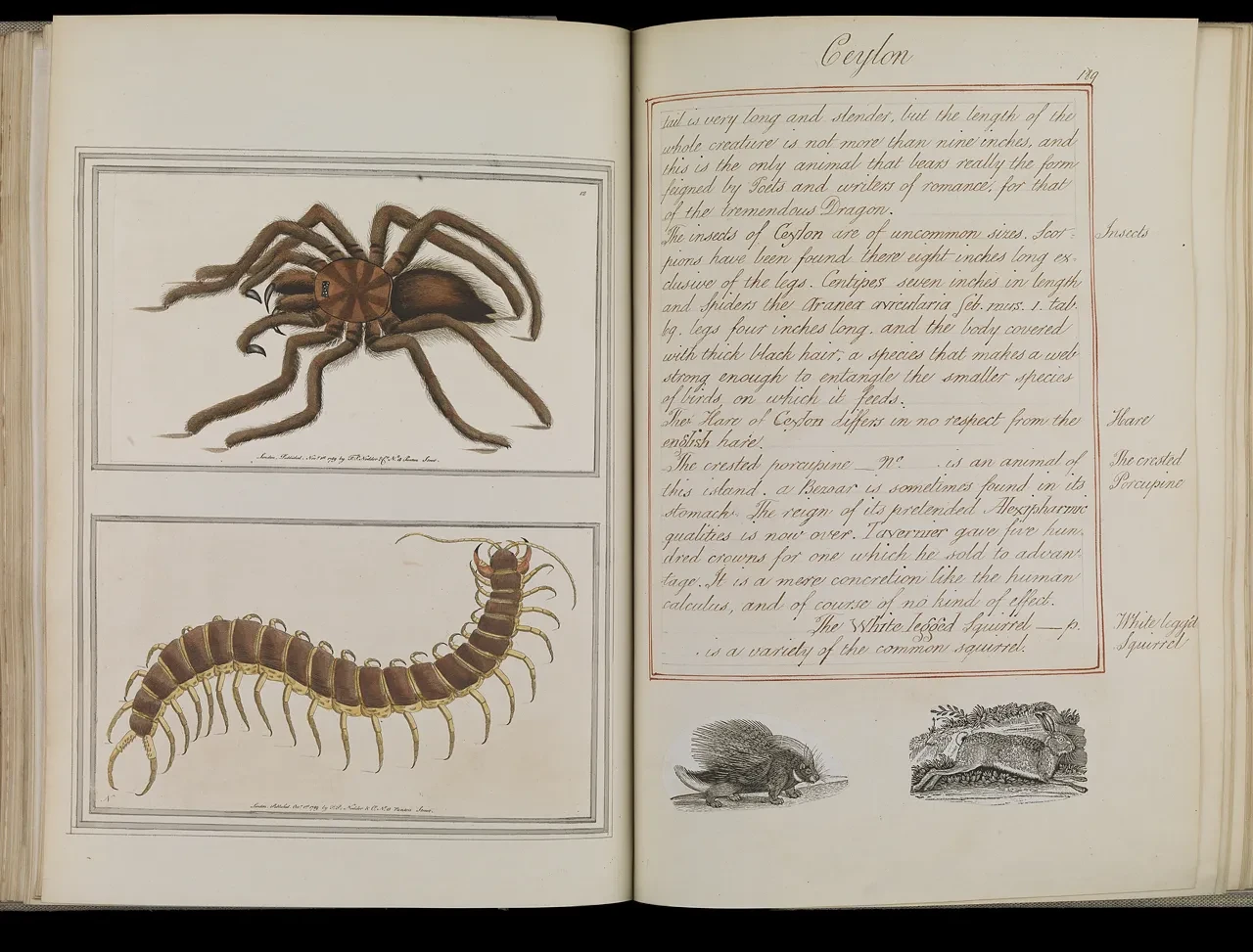

I have collected every information possible, from books antient and modern: from the most authentic, and from living travellers of the most respectable characters of my time. I mingle history, natural history, accounts of the coasts, climates, and every thing which I thought could instruct or amuse. They…make a folio of no inconsiderable size; and are illustrated, at a vast expense, by prints taken from books, or by charts and maps, and by drawings by the skilful hand of Moses Griffith, and by presents from friends.

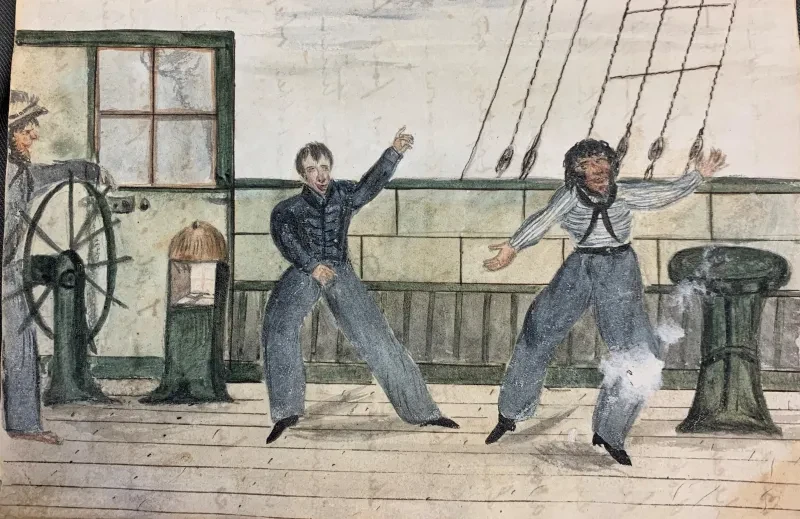

Why, then, should we pay any attention to the work of this proud armchair traveller? Well one reason is the visual extravaganza offered to readers of the ‘Outlines’ volumes: they were lavishly illustrated, with marginal drawings and title pages by Griffith, countless costly insertions from books and print shops, and original art by—amongst others—the marine painter Nicholas Pocock (1740–1821) and the natural history specialist Sarah Stone (c. 1760 – 1844). As a visual guide to the eighteenth-century world as seen from a gentleman’s study, ranging from sparse navigational renderings of coastlines to detailed landscapes and portraits, the volumes are undeniably spectacular to look at.

Another reason, though, is the evidence we get from Pennant about how an eighteenth-century Welsh author of his class could gain knowledge of the world beyond Europe—and the answer is inevitably tied to the far-reaching and ever-extending networks of eighteenth-century empire. The ‘authentic…living travellers’ and generous ‘friends’ consulted by Pennant included many who were directly involved in the administration of overseas colonies—obvious sources to tap for an internationally prominent naturalist and respectable gentleman author. Take, for instance, Pennant’s two volumes on India (or ‘Hindostan’): these thank such figures as Elijah Impey (1732–1809) and his wife Mary Impey (1749–1818), the former a returned chief justice of British-controlled Bengal; Nathaniel Middleton (1750–1807), a recently-returned East India Company employee; and Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789), the former governor of Dutch-controlled Sri Lanka. Thanked in the project’s three African volumes are Philip Stephens (1723–1809), secretary to the Admiralty—an institution centrally involved in Britain’s imperial expansion—and perhaps most disturbingly, a man described as 'my worthy friend Richard Wilding esqr. of Llanrhaiadr’, a compatriot of Pennant in north-east Wales, and a prominent trader in enslaved Africans. When Pennant had questions about the physical characteristics of people living in West Africa—itself a sign of the project’s investment in contemporary racializing discourses—it was to someone who sold Africans for profit that he turned for information.

The text of the ‘Outlines of the Globe’ is not always jingoistically imperialist—Pennant could in fact be surprisingly critical of empire. He was dependent on any sources he could get his hands on, and despite offering thanks and apologias for his imperial information-gatherers, he was also willing at times to trust the horrific accounts of abolitionists campaigning against slavery, or the reports of British atrocities during the Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780–1784). Pennant even wrote passages that endorsed violent resistance against European imperial powers by people in South Asia and West Africa—though he referred to the latter using the archaic and racialised geographical term ‘Nigritia’, no longer in use today. He claimed in one volume that ‘the frequent barbarities of the europeans over the natives of their usurped dominions hardens my heart against any calamities which befall them either from the hand of the oppressed Indians or captived Nigritians’ (P/16/12). But without testimony provided by the agents of imperialism—in particular his ‘friends’ in colonial service, in the institutions of transatlantic enslavement, and in the armed forces that protected Britain’s empire—Pennant’s ‘Outlines of the Globe’ manuscripts simply would not exist. Trying to view the globe from the safety of one’s estate in Flintshire meant taking advantage of the web of colonial connections that linked Wales to the rest of the world.

Pennant’s Welshness has been cited as a reason why his published tours of Scotland were so well received by Scots: as a Briton from a country similarly distanced from the English metropole, he could bring a ‘transperipheral’ perspective that was (for instance) unfazed by the continuing existence of the Gaelic language in Scotland, given the similarly continuing existence of Welsh in Wales. However, this level of sensitivity was only possible because Pennant worked with knowledgeable local collaborators in Scotland, ensuring some level of linguistic and cultural accuracy. His informants for the ‘Outlines of the Globe’, on the other hand, were overwhelmingly Europeans, often directly involved in the colonisation of overseas territories. The ‘Outlines’ features a rather starry cast of characters—Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820), voyager on Cook’s Endeavour, appears more than once—but the view the work centres is fundamentally that of the colonial observer.

What Pennant’s ‘Outlines’ offers us, then, is the eighteenth-century globe as seen through imperial eyes from Wales, despite its occasionally strident disavowals of European imperial practices. Pennant, the imaginary tourist, thus becomes a version of those Welsh writers who, according to the Welsh-Guyanese scholar Charlotte Williams, created a convenient image of other continents as seen ‘with the eyes of Wales’: ‘[t]hey had to tell about their work in a way that condemned exploitation and plunder and disassociated itself from the forces of colonialism… They used the same maps as the colonisers, took the same routes and byways, but they were not the ones who turned the villages blood red’.

Further Reading

-

Thomas Pennant, The Literary Life of the Late Thomas Pennant, Esq. (London, 1793)

-

Mary-Ann Constantine and Nigel Leask (eds), Enlightenment Travel and British Identities: Thomas Pennant’s Tours in Scotland and Wales (London: Anthem, 2017)

-

Charlotte Williams, Sugar & Slate (Aberystwyth: Planet, 2002)