When thinking of the role of the Royal Navy during the First World War we normally focus on the Grand Fleet, the Battles of the Falklands and Jutland or perhaps the Navy’s role in protecting merchant shipping from the threat of German U-Boats. But this only shows part of the First World War experience for Royal Naval personnel, some of which was not at sea at all.

Away from the fleets, naval personnel served in units onshore, in the trenches and in the air. In this blog, I would like to highlight two items from our collections that show something of how naval personnel experienced life in the trenches during the First World War.

We have several small personal collections covering the service of men from the Royal Naval Division which was formed from Royal Navy and Royal Marine reservists who were not required for service at sea. The division, whose battalions were named after famous naval figures such as Drake, Hawke and Nelson, would see service at Antwerp and Gallipoli. Later it was placed under army command and participated in many of the major battles on the Western Front from 1916 onwards.

Descriptions of life in the trenches

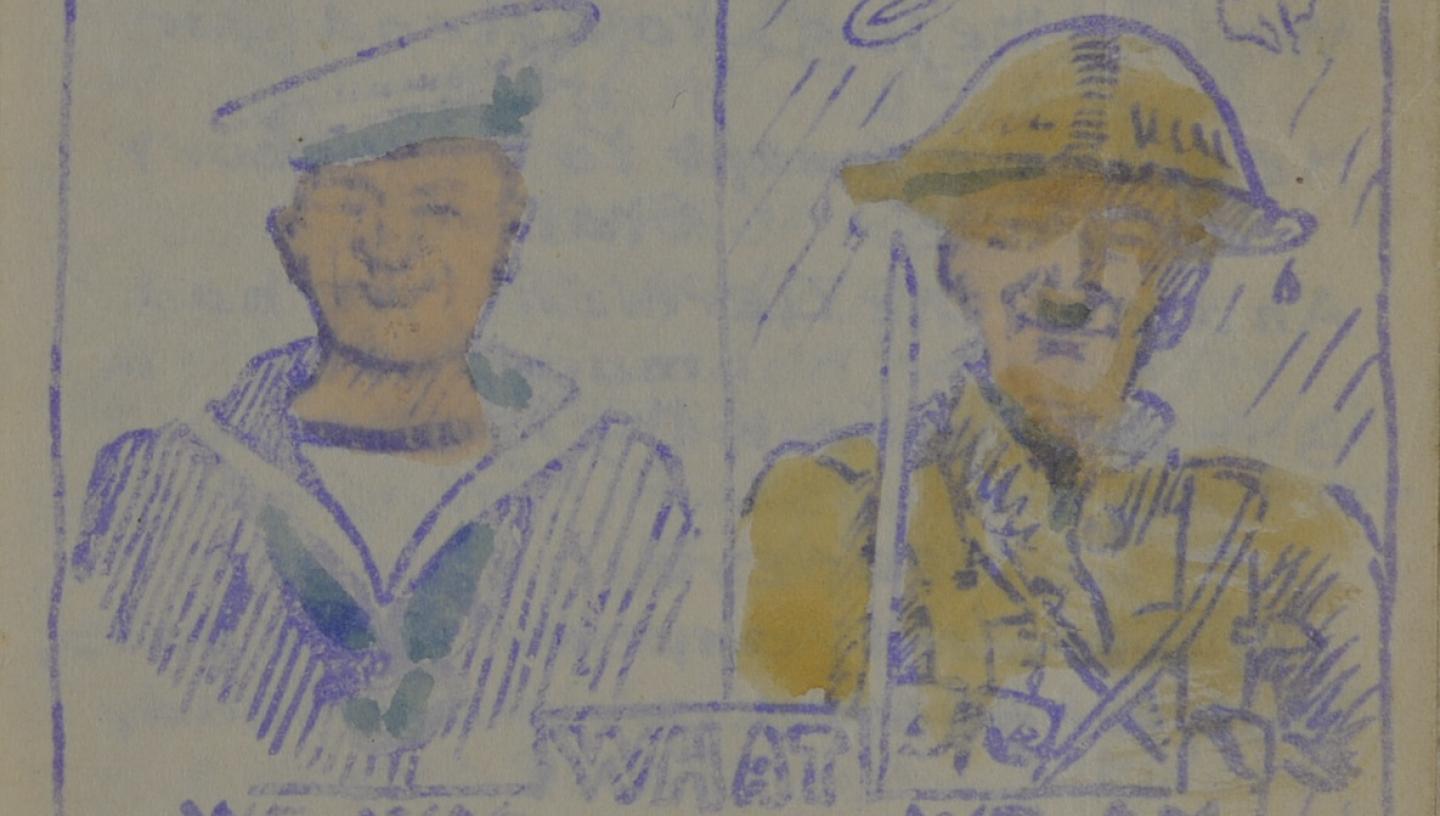

One example is MSS/84/068, a scrapbook created by Sub-Lieutenant Albert E. Dossett of Drake Battalion. As you would expect, it is filled with newspaper clippings covering details about the war, but it also has various other items of ephemera within it too. One of these items is a small ‘magazine’ evidently produced for the unit described as ‘The magazine upon which the mud never dries’.

Across eight pages with several illustrations, the magazine covers Christmas celebrations but mainly focuses on humorously describing various aspects of trench life. One page describes the difficulty of getting any sleep while another provides some commentary on what must have been everyday occurrences and irritations for all of the men, such as banging their heads on the roof of their dugout or finding themselves sinking into several feet of mud. It ends with an image of remembrance for their fallen comrades ‘The Drakes who have gone west’.

A sailor on land – visiting the trenches

Another interesting account we hold is the journal of Chief Stoker E.C. Markquick who in 1916 was serving in HMS Britannia as part of the Grand Fleet. However, he was also one of a group selected from the Grand Fleet in January 1916 to visit the trenches in Flanders and his diary of this experience survives in our collection as JOD/63.

His account of this visit provides almost a tourist’s view of the Western Front, describing it from an outsider’s perspective and as someone who knew he would soon leave and return to the fleet. As the visit seems to have partly functioned as a publicity stunt and was reported on in The Times, it seems likely he had a fairly curated experience of life at the front but, as his account records, not one entirely devoid of danger.

Journey to the trenches

The group journeyed first to London by train and then on to Folkestone where they boarded a Belgian paddle steamer to Boulogne along with other troops heading to the front. From there they travelled to Cassel in repurposed London buses on roads that were ‘one countless mass of traffic, motor & horse’. On arrival they were given a welcome dinner and he noted with pride that he ‘personally shook hands with Captain Wright of the Scott S. Polar Expedition’ who was serving in the Royal Engineers at that time.

Having been welcomed, they spent the next day on a tour of the wireless communications station nearby, were given training in the use of gas masks and subjected to a mock gas attack. The party was then divided up into groups and taken to different sections of the front.

He notes that the resources in the camp just behind the line were not great, describing it as ‘nothing but a barren space of mud with series of tents’. The naval party were to be quartered in the only wooden hut in the camp, one usually reserved for the wounded or those suffering from trench foot, presumably adding to a feeling of being out of place.

The next day, they were instructed in the use of rifles, grenades, and other equipment. After this period of instruction, they began to move up to the firing line which involved a march on roads ‘in shocking condition, being torn up by shell and about 12 or 14 inches deep in mud’ arriving at 7:45pm.

Now commenced a walk that I am sure I shall never forget & I am much afraid words will never describe. Shells seemed to be bursting everywhere & the noise was deafening & an occasional star shell would make the sky as light as day … we crossed a ditch & started floundering on through mud up to our knees every now and then falling over tripping wires.

At the front lines

On reaching the firing line, he was to be ‘shown everything of interest during the night’ with the first group of soldiers he spent time with insisting he strafe the enemy trenches with their Lewis Gun. He was then taken to the point in the line closest to the enemy positions where they could just about hear the German soldiers talking in the distance.

Later he spent time working with soldiers repairing and strengthening the barbed wire that was present everywhere. He notes that it was ‘dangerous work and rather exciting … it is amazing what few casualties there are considering the number of bullets flying about.’ Having spent several hours doing this and talking with some Canadian soldiers nearby, he was advised to get some sleep but found this impossible with the constant noise of artillery and machine gun fire.

Several gas attack scares then occurred which allowed him to put his earlier training to good use. At 6:15am, five men were killed by a shell that exploded nearby and another four by rifle fire with several others wounded, though apparently none of the naval party.

The closest Markquick himself would come to injury was when a shell hit close to a dugout in which he and several other men were eating lunch ‘blowing it to pieces … fortunately none of us were seriously hurt, nothing worse than scratches. I covered my eyes with my hands & consequently my wristwatch which was exposed was smashed.’

Trench life

He was obviously extremely interested in the technical side of things, describing how a rifle grenade functioned or the construction and layout of the trenches in some detail, including several simple hand drawn maps of the trenches. Much of the journal is taken up with descriptions of trench life and the various jobs soldiers were doing.

His hosts had obviously been instructed to allow him to try various things during his visit, including the use of a sniper’s rifle fitted with a periscope ‘through which I could plainly see three men working on the German parapet, I fired six rounds and two of them apparently fell and the other disappeared, but whether they were injured or not it was impossible to say.’

Having spent about a day and a half in the trenches, they eventually moved to the rear and were taken to inspect the stores and local aid stations to see how the wounded were treated. The following day was spent touring various local artillery batteries which included a few former naval guns. Once again they were allowed to operate equipment and test fire the guns at the German lines in the distance.

After visiting a few other locations, including British positions near Ypres, they returned to Cassel for a farewell dinner and the following day departed for Boulogne and their return journey. They were then granted a day’s leave in London before travelling north by train to re-join their ships. As they left he reflected on the experience, perhaps glad to be returning to the fleet.

The one thing that struck us most was the real good spirit which prevailed, everywhere we went we saw pleasant smiles, never heard a harsh word or saw a frown. The daily life of the soldier is one of continuous hardship & dangers & his existence most miserable …