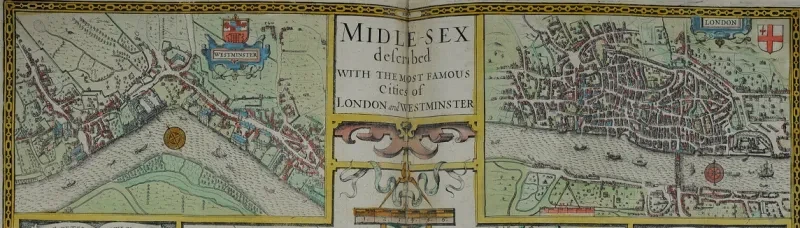

In this blog we look at cartographer John Rocque's An Exact Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, ‘the outstanding plan of the capital in the eighteenth century’

One of the treasures of the Caird Library is a bound atlas depicting detailed, coloured views of London as if seen from the air. It shows us the capital as it was during the reign of George II through the eyes of one of the city’s adopted sons, John Rocque.

John (né Jean) Rocque (died 1762) was a Huguenot émigré who came to Britain, probably in 1709, and settled in London during the 1730s. Rocque was a cartographer, surveyor and print-seller. Before producing this volume, he had surveyed towns and estate gardens, and he went on to produce maps of other towns in the British Isles and on the European mainland.

Rocque lived at various London addresses over the course of his career. He resided at Great Windmill Street, Soho (by the boundary of the area which was home to London’s French community). Later he lived in Piccadilly, then Whitehall (where he lost his possessions in a fire), before relocating his business to the Strand.

An exact survey of the cities of London and Westminster, the borough of Southwark, with the country near ten miles round by John Rocque (RMG ID: PBC5317) was planned by John Rocque and John Vertue. Surveying began in 1738 and the atlas was published in 1746. As its title indicates, it included areas which were at that time several miles beyond London’s boundary.

Our copy of the atlas is the 1746 edition and contains 16 coloured maps. The areas depicted include Blackheath and Greenwich, which are readily recognisable today, albeit that Blackheath had not yet been landscaped and is shown as comprising trees and pasture. This made it a suitable haunt for highwaymen, such as Claude Duval (who was known to have operated on the heath during the previous century).

The Royal Hospital can be seen by the river and the Royal Observatory was already located in Greenwich Park. The Queen’s House is shown as the Governor’s House, but there is no sign of the Royal Hospital School buildings which are the present-day home of the National Maritime Museum (the buildings are of later construction, though the school already existed).

The volume contains a list of subscribers, among whom were the Dukes of Devonshire and Richmond, the Worshipful Company of Skinners, the Royal Exchange Assurance Company, Mr Kellom Tomlinson (described as the ‘Author of the Original Art of Dancing’), and Mr Samuel (described as a ‘Bird Frame-Maker’). The latter subscribed to two sets.

The atlas’s key provides a guide to the symbols used and allows us to identify the different uses of the land depicted. Plate VII, for example, shows Oxford Street, with fields (pastureland) to the north. There were also fields in what is now Bloomsbury, with orchards in Bedford House, just off Great Russell Street. The Foundling Hospital is located in countryside (Lambs Conduit Fields), though only just (it lies a little to the north of Great Ormond Street).

At the western end of Oxford Street, just north of Hyde Park, and onto Plate XI, is ‘Tybourn’ with a depiction of Tyburn Tree, the multiple gallows where condemned prisoners were hanged. Elsewhere, south of the river at Lambeth (Plate VI), there are gardens.

Meandering through the city, then as now, is the river Thames. The riverscape is represented by ships and other vessels, with the various stairs located at points along the banks shown with their names. At this time, the river was wider than it is today because it had not yet been embanked.

Rocque’s survey of London has been described by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as ‘the outstanding plan of the capital in the eighteenth century’. It ran to several other editions, including posthumous ones since Rocque’s widow, Mary Ann, continued the business after her husband’s death.