Discover documents that shine a light on the experiences of captured British and French sailors and soldiers in the National Maritime Museum's Caird Library.

The Caird Library has recently installed a new display of archive and library material. The theme is Prisoners of War at Home and Overseas, 1793-1815, and it reveals what life was like for the men and boys captured during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

During this period, hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war were held captive at depots, barracks, and on board prison ships all over the world, from North America to the Indian Ocean. The documents on display focus on the experiences of captured British and French sailors and soldiers.

Breakdown of Exchange

In the years before the French Revolution, the established tradition had been to exchange and return prisoners to their respective countries. However, between 1793 and 1815, negotiations for exchanges -known as cartels - broke down and very few cartel ships sailed. Napoleon did not release any British captives, including non-combatants, believing that all able-bodied men had the potential to fight against the French.

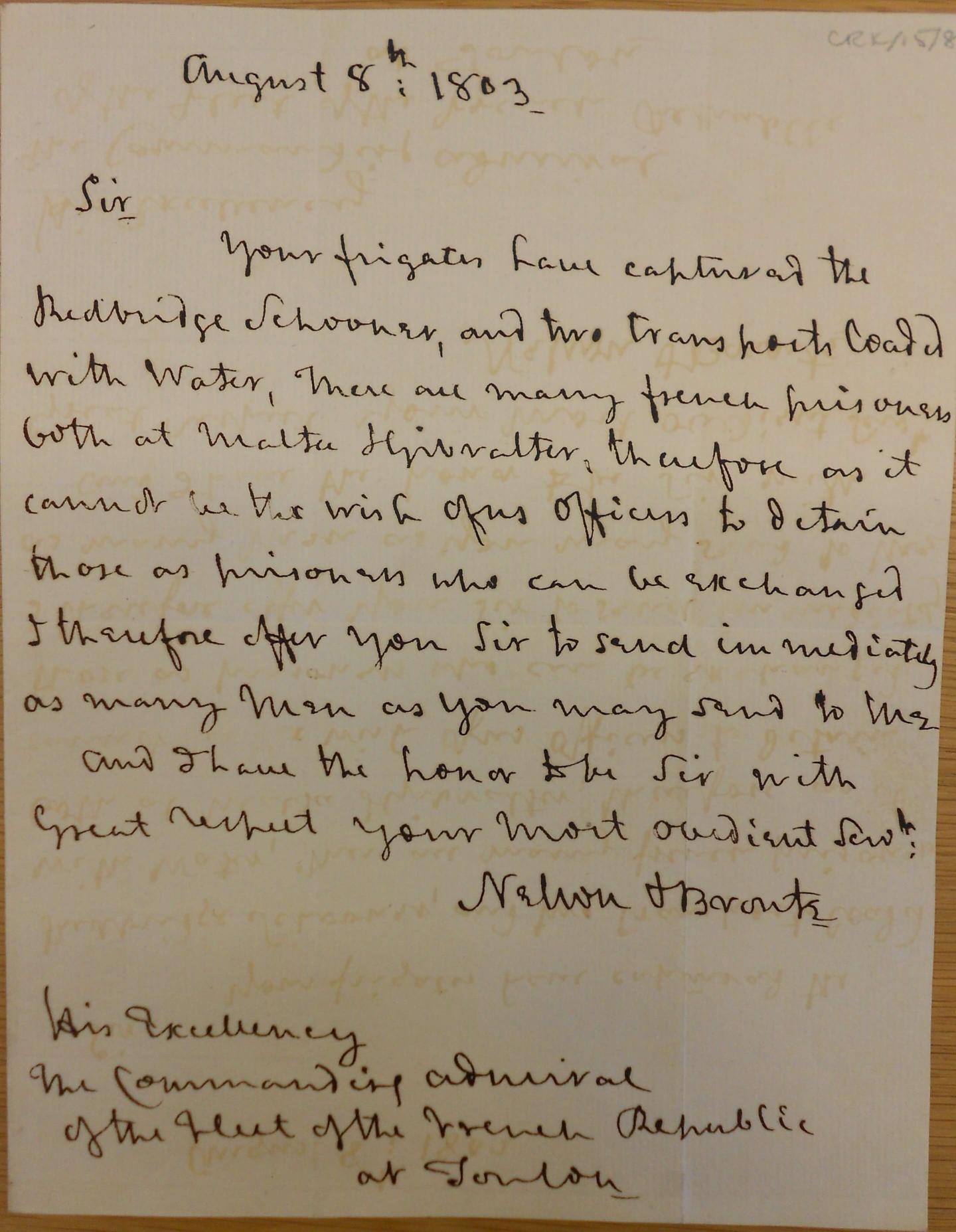

One letter, addressed to the Admiral commanding the French fleet at Toulon in August 1803, deals with the subject of prisoner exchange (NMM ref: CRK/15/8). Written by Lord Nelson, who was at that time commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean fleet, it asks for the amicable exchange of captured men. Nelson writes:

“there are many French prisoners both at Malta and Gibraltar, therefore as it cannot be the wish of us officers to detain those as prisoners who can be exchanged I therefore offer you sir to send in immediately as many men as you may send to me”.

Nelson’s fleet attempted to send a boat to Toulon under a flag of truce, but the French refused the proposal and the men held on board endured eleven years of captivity. They were released after Napoleon abdicated on 14 April 1814.

Life as a Prisoner

Captured officers lived in relative comfort. On parole in Britain, the officer classes were stationed at private houses in small country or market towns, from the Scottish Borders to the South Coast. Around four thousand officers from different enemy nations were on parole in Britain by 1814. They were given an allowance by the Transport Board and enjoyed a reasonable amount of freedom, interacting with society, using lending libraries and holding concerts. When the war ended, some men chose to stay behind with their families. Across the channel at Verdun, British prisoner of war John Robertson wrote in his journal (NMM ref: JOD/202/1) of the gentlemen’s clubs and gambling houses enjoyed by English officers in France. Excluded by his class as a lowly sailor, Robertson criticised the coaches and gold-laced footmen of the “English nobbs” who knew little of captivity.

Unlike the higher ranks, ordinary soldiers and sailors were forced to endure harsher living conditions. In Britain, crammed on board captured ships and into overcrowded barracks, men were often issued with mouldy rations and inadequate clothing. Poor sanitation and bad air quality also put them at risk of contracting disease. Agents were assigned by the Transport Board to act as intermediaries between prisoners of war and their captors. They were placed in charge of ensuring that rations and clothing were sufficient, and were duty bound to report any acts of negligence. Despite the administrative measures put in place to protect them, prisoners of war could still be at the mercy of corrupt overseers.

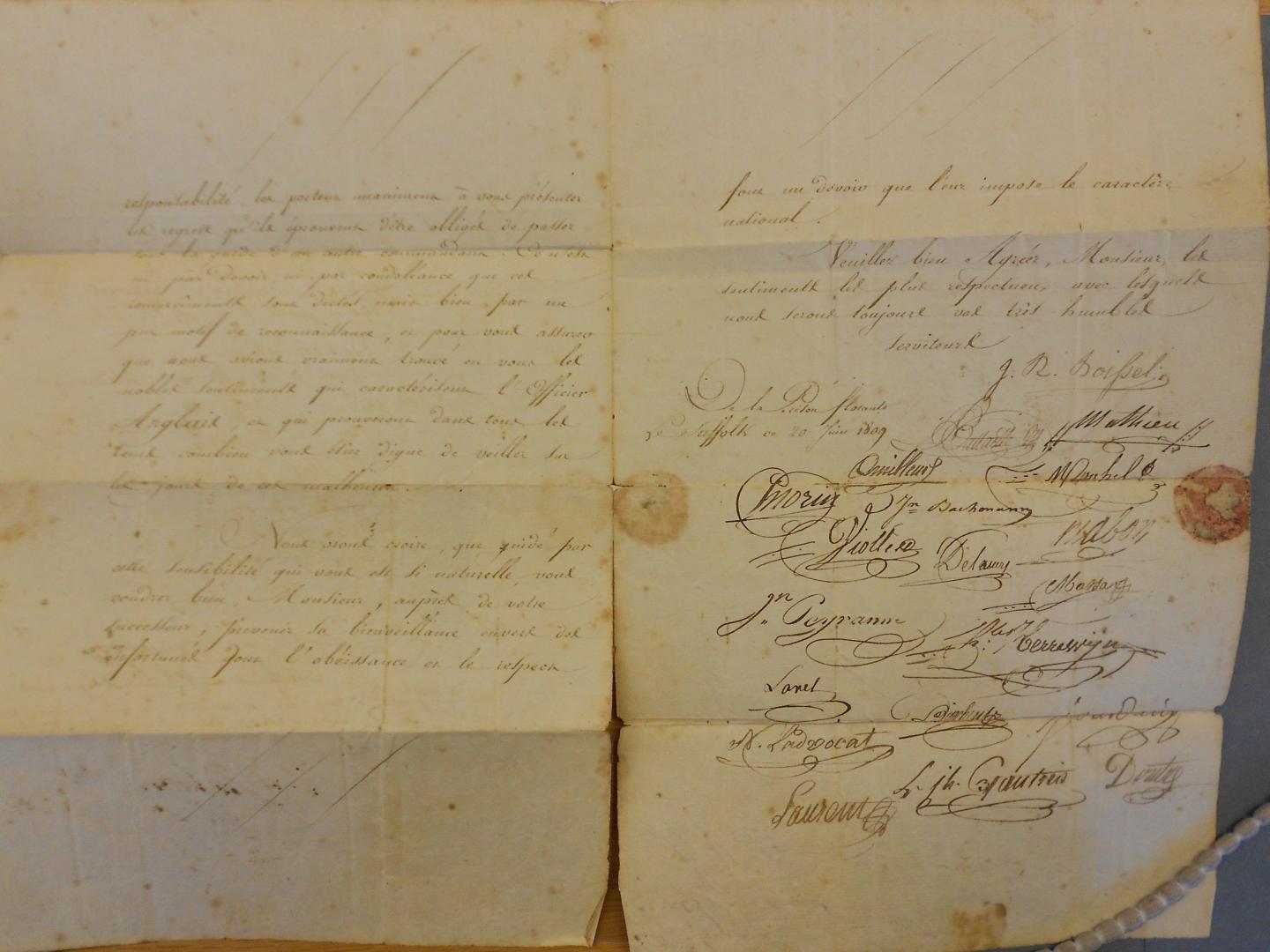

A letter written in June 1809, from French prisoners of war to naval officer Sir James Gordon Bremer, shows a more positive experience. Rather than suffer at the hands of their captors, the prisoners on board the HMS Suffolk wrote to express their regret at the commanding officer’s departure (NMM ref: AGC/B/25/3 (1)). During the thirty months of their detainment, the men remarked upon:

"la bienveillance et l’humanitié que vous avez marquées à tous les prisonniers de votre prison / the benevolence and humanity that you have shown to all the prisoners in your prison".

With Bremer leaving the Suffolk for a new post, the prisoners on board collectively signed the letter -akin to a goodbye card- writing:

"nous avons vraiment trouvé en vous les nobles sentiments qui caractérisent l’officier Anglais / we have truly found in you the noble sentiments which characterise the English officer".

Bremer’s respect of the prisoners under his care was not unusual, but it was certainly appreciated by those who received it.

Creativity in Captivity

A defining aspect of captivity was boredom. To cope with this, many prisoners made souvenirs to sell to the public, saving scraps of bone and straw to make intricate ship models, miniature guillotines and domino boxes. In addition, men kept diaries documenting their experiences. Louis Garneray’s Mes Pontons is perhaps the most famous account of a French prisoner’s experience on board prison ships at Portsmouth harbour. However, the National Maritime Museum holds a journal to rival that of Garneray. Held captive in France, Midshipman Joseph Pape kept a remarkable illustrated account of his experiences as a sailor (NMM ref: JOD/250).

Pape begins his journal in rhyme:

“When first I took my pen in hand, to draw I did not understand, but when I pusht (sic.) on and strove I thought if I continued I might improve. I being a prisoner in France its true, perhaps unknown to many of you, weary of this prison I use, to be, so I begun this work which here you see, what I have done here you will find, it was only to amuse my mind, if you see any fault my worthy friends, excuse a little and what you can commend.”

No larger than a postcard, the pages of Pape’s journal are scattered with coloured drawings and poems documenting his travels. His sketches of ships and militiamen give us a fantastic insight into the daily life of an eighteenth-century sailor. Pape produced images of men at work and play, foreign countries, ships in battle and popular stories. Though he declared himself a novice, Pape’s pictures speak of a wealth of experiences. It is probable that his pictures and poems were passed amongst other prisoners, read aloud and shared.

Conclusion

The documents on display outside the Caird Library show that the business of captivity was a complex one. Dialogues between prisoners and captors, officials and enemies, were surprisingly open and vocal. Living conditions fluctuated on both sides of the channel, yet the men held in Britain and France still found ways to be enterprising and creative. Their letters, diaries and drawings show frustration, isolation and anxiety. Held for years on end, prisoners demonstrated great resilience. When peace was declared and they were at last permitted to return home, almost a quarter of a century of conflict had passed. War had moved closer to home, no longer located far out at sea, or on distant battlefields. Civilians had been touched by this conflict; they saw prisoners in their towns, villages and ports. Ultimately, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars had a huge impact on civilians, politicians and prisoners alike. The effects of the conflict would go on to shape the social, cultural and political values of multiple nations for years to come.

To learn more, come and see the display case, situated outside the Caird Library until the new year.

Anna McKay, collaborative doctoral student at the National Maritime Museum and the University of Leicester. Anna’s thesis is entitled, “The History of British Prison Hulks, 1776-1864”.