In this blog we look at the larger-than-life characters who carried people and goods on London’s river in centuries gone by.

Among the colourful characters of the River Thames in a bygone era were lightermen and watermen, whose job it was to transport people and goods on the river. Their successors are still with us today, operating on a river which is a good deal quieter than that of their boisterous predecessors!

Watermen carry people (and their luggage). Lightermen carry goods - they lighten (that is, unload) a ship and transfer her cargo to another vessel, or to shore.

Since 1700, both watermen and lightermen have been members of the same livery company or guild, The Company of Watermen & Lightermen of the River Thames. The Company was founded in the sixteenth century and is located in the City of London.

Centuries ago the Thames was, on the one hand, London’s thoroughfare, and on the other a barrier separating London into two halves. Watermen therefore provided people with a means of both travelling quickly through the city at a time when roads were slow and uncomfortable, and of crossing from one bank to the other at a time when there were fewer bridges than there are today.

A sense of how watermen were seen as the fastest way to travel in London can be gleaned from Samuel Pepys’s diary of 27 December 1667, where Pepys records that he went 'away by coach to the Temple and then, for speed, by water thence to White-hall'.

Another (unidentified) seventeenth-century witness, quoted by Joan Tucker in her book Ferries of the lower Thames (RMG reference: PBH3556), remarked on the speed and dexterity of watermen in their boats (of a type called wherries):

the wherries shoot along so lightly as to surprise everyone … They row like galley oarsmen, with extremely long oars, and are very dextrous at steering clear of each other.

Wherries could be rowed and steered by a waterman on his own or with an apprentice, and could be beached to enable passengers to alight more easily.

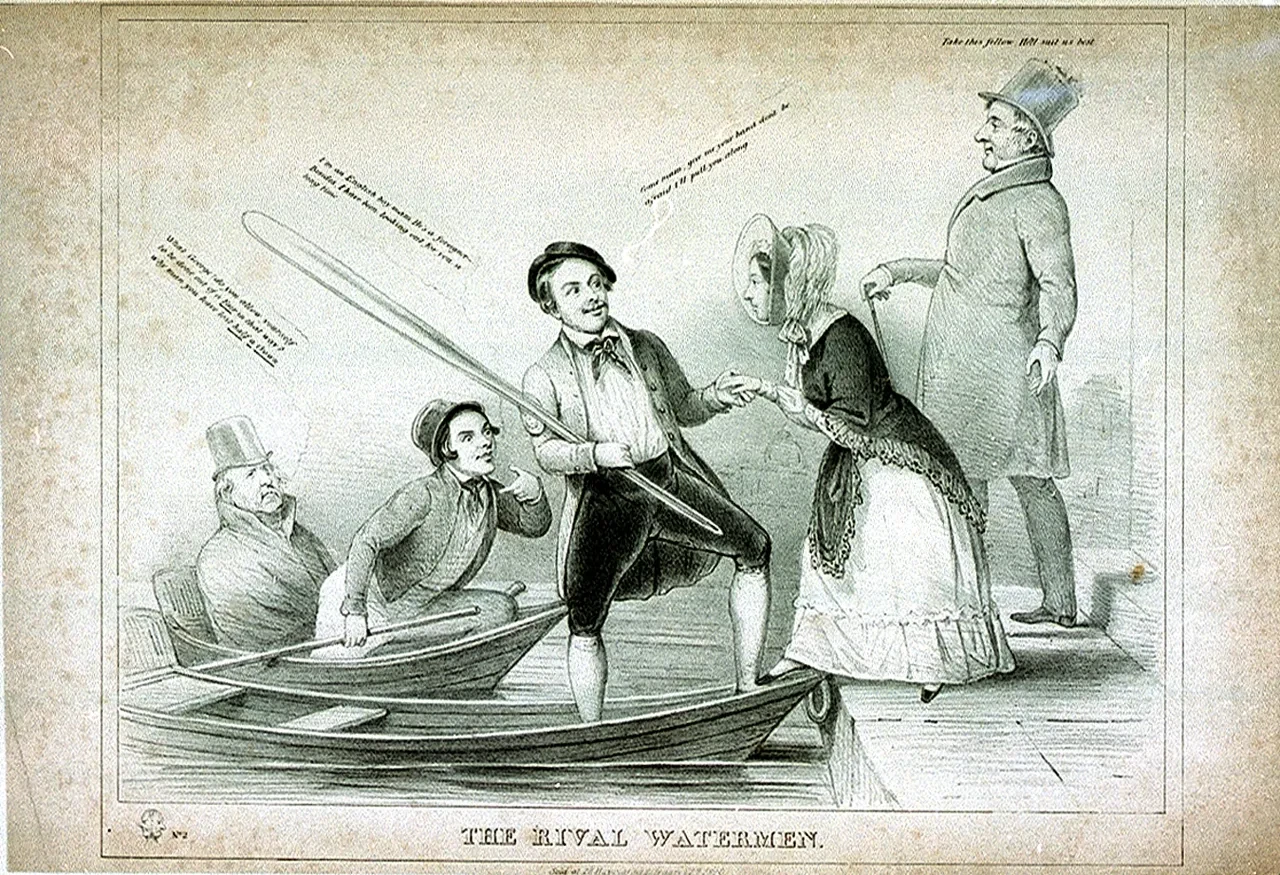

Besides their prowess on the river, watermen were also known for their verbal prowess. They called out to attract potential passengers and verbally abused the waterman who was successful in procuring the business. They also insulted other people on the river.

Joan Tucker quotes César de Saussure, who wrote in 1725 that ‘the conversations you hear are most entertaining … Most bargemen are very skilful in this mode of warfare using singular and quite extraordinary terms, generally very coarse and dirty’.

Henry Mayhew noted that the number of Thames watermen had declined by the time he profiled them in London labour and the London poor (1861) (RMG reference: PBF5076). By this point the oar was being replaced by steam as the locomotive force on the river.

‘An old waterman’ to whom Mayhew spoke blamed the new London Bridge for the watermen’s decline:

[P]eople may talk as they like about what’s been the ruin of us—it’s nothing but new London Bridge. When my old father heard that the old bridge was to come down, ‘Bill,’ says he, ‘it’ll be up with the watermen in no time. If the old bridge had stood, how would all these steamers have shot her? Some of them could never have got through at all. At some tides, it was so hard to shoot London Bridge (to go clear through the arches), that people wouldn’t trust themselves to any but watermen. Now any fool might manage. London-bridge, sir, depend on it, has ruined us.

The steamers affected the watermen’s trade in another way too. Mayhew interviewed a waterman near the Tower of London, who told him:

There’s very few country visitors take boats now to see sights upon the river. The swell of the steamers frightens them. Last Friday a lady and gentleman engaged me for 2s. to go to the Thames Tunnel, but a steamer passed, and the lady said, ‘Oh, look what a surf! I don’t like to venture;’ and so she wouldn’t, and I sat five hours after that before I’d earned a farthing. … The good times is over … We’re beaten by engines and steamers that nobody can well understand, and wheels.

Mayhew counted 75 stairs where the watermen at that time plied their trade:

Near the stairs below bridge the watermen stand looking out for customers, or they sit on an adjacent form, protected from the weather, some smoking and some dozing. They are weather-beaten, strong-looking men, and most are of, or above, the middle age. [They] … wear all kinds of dresses, but generally something in the nature of a sailor’s garb, such as a strong pilot-jacket and thin canvas trousers.

The present race of watermen have, I am assured, lost the sauciness (with occasional smartness) that distinguished their predecessors. They are mostly patient, plodding men, enduring poverty heroically, and shrinking far more than any other classes from any application for parish relief.

According to Mayhew, all the watermen lived ‘in the small streets near the river, usually in single rooms’. At least three-quarters had apprentices, mostly sons or other relatives, and many of these went on to become seamen in the merchant service, and some in the Royal Navy.

Lightermen’s boats, noted Mayhew, were adapted to convey a particular cargo, be it ‘corn, timber, stone, groceries and general merchandise’ and usually stuck to that particular good. Some lightermen owned their own boats and were ‘a prosperous class compared to the poor watermen.’ They might also employ other hands and have offices or other addresses where they could be contacted.

Lightermen did not ply their trade in the same way as watermen, but still kept an eye out for opportunities. They were known to board a recently arrived vessel ‘and offer their services to the captain … or they ascertain to what merchant or grocer goods may be consigned, and apply to them for employment in lighterage.’

Each lighterman agreed his own prices, but if induced to accept a tough bargain he might try and drive the boat solo even where this was inadvisable. Lighters also required the assistance of the tide:

Lighters can only proceed with the tide, and are often moored in the middle of the river, waiting the turn of the tide, more especially when their load consists of heavy articles. The lighters, when not employed, are moored alongshore, often close to a waterman’s stairs.

Lightermen, according to Mayhew, were of a similar character to watermen and, like them, lived close to the river, though the better economic circumstances of those who owned their own boats allowed them to live more comfortably.

If you are interested in researching watermen and lightermen, please note that most of the post-1666 records are housed at the Guildhall Library. Sadly, almost all the records of the Company of Watermen prior to this date were destroyed in the Great Fire of London.

For online research, FindMyPast (available to access in the Caird Library) contains, amongst others, the dataset ‘Thames Watermen & Lightermen 1688-2010’, which includes records from The Company of Watermen & Lightermen of the River Thames.

The Caird Library also has some published works on Thames watermen and lightermen, including:

Harris, Harry (1978): Under oars. Reminiscences of a Thames lighterman 1894-1909. London: Centerprise Trust. (RMG reference: PBN1652 and PBH0873)

Legon, James W. (2008): My ancestors were Thames watermen. A guide to tracing your Thames watermen and lightermen ancestors. London: Society of Genealogists Enterprises. (RMG reference: PBH2417)

Mayhew, Henry (1861): London labour and the London poor. London: Griffin, Bohn and Company. (RMG reference: PBF5076)