In this blog we highlight a little cookery book which provides a glimpse into the types of meals eaten at sea in the last years of Queen Victoria's reign and which also reflects the change in status of ships' cooks.

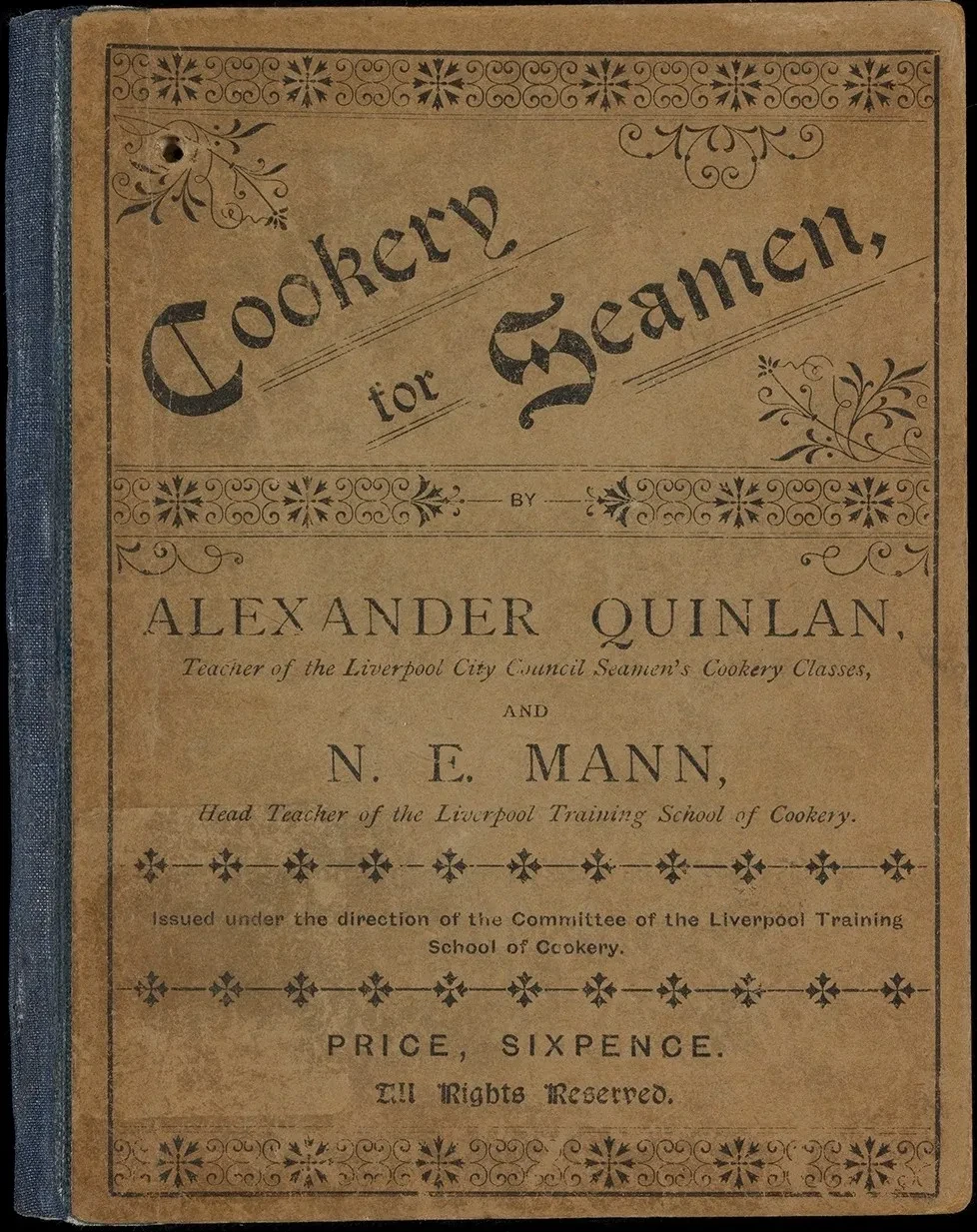

In 2019, when our Publishing team were seeking ideas for small books in the Caird Library’s collection which could be republished as facsimile editions, one of the works I suggested was a late Victorian cookbook called Cookery for Seamen.

Why the book was originally published

First published in Liverpool in 1894 by C. Tinling and Co., it aimed to provide recipes which were practicable for ships’ cooks to prepare, as well as giving advice for the care and butchery of livestock at sea. At this time the duties of a ship’s cook extended to caring for a ship’s on-board farm, as well as (in some cases) slaughtering and butchering the animals. The book’s Introduction sets out its aims:

‘Although there are literally Cookery books for the million, few of these are helpful to a Seaman, and it is hoped the following instructions and recipes, prepared specially for Sea Cooks, by a Sea Cook, may supply a want which has been more keenly felt than expressed. They are the outcome of 21 years of practical experience at sea, and of two years’ endeavour on shore to give the benefits of that experience to others.’

The Introduction continues by setting out the extra challenges which ships' cooks face compared to cooks on land:

‘The work of a Cook at sea is, in most ways, much more difficult than that of one on shore. Where there is no market, its place must be taken to a very large extent by forethought, and this, not only in the providing – which is not always in the Cook’s hands, but in the careful stowing and storing of his goods.’

The diminutive size of the book is no doubt also the result of careful consideration: unlike many of today’s weighty – if visually stunning – cookbooks, it could fit more readily into the limited storage space available to ships’ cooks.

According to the book’s Preface, the book was published following requests which seamen made for recipes to the Liverpool Training School of Cookery. The School’s founder and Honorary Secretary, Fanny Louisa Calder, wrote the Preface. When Calder founded the School in 1875 it was for female students only, but later it opened its doors to males and, in 1891, began providing classes for ships’ cooks.

The authors

The authors of this book, Alexander Quinlan and N.E. Mann, were both cookery teachers. N.E. Mann was the Head Teacher at the Liverpool Training School of Cookery, whilst Alexander Quinlan taught the Liverpool City Council’s seamen’s cookery classes.

N.E. Mann was in fact Miss E.E. Mann. Ellen Esther Mann (1854–1928) was born in Birkenhead, the daughter of a Methodist minister. She was also the author of a publication for use in teaching household laundry work. It is not known why her name is cited as N.E. Mann on both these publications. Perhaps she was known as ‘Nelly’ or ‘Nell’?

Alexander Campbell Quinlan (1859–1929) was a ship’s cook. Born in Liverpool, he was, by 1881, working as a cook on board the SS Mallard. Ellen Mann trained him to teach and, like Mann, he appears to have continued in the teaching profession, being listed as an Instructor of Cooking in the 1901 Census.

What Mann and Quinlan were therefore able to do was to harness their joint skills and experience, Mann’s as a domestic science teacher and Quinlan’s as a sea cook, and produce this little volume to help sea cooks cook better, and passengers and crew eat better, while at sea.

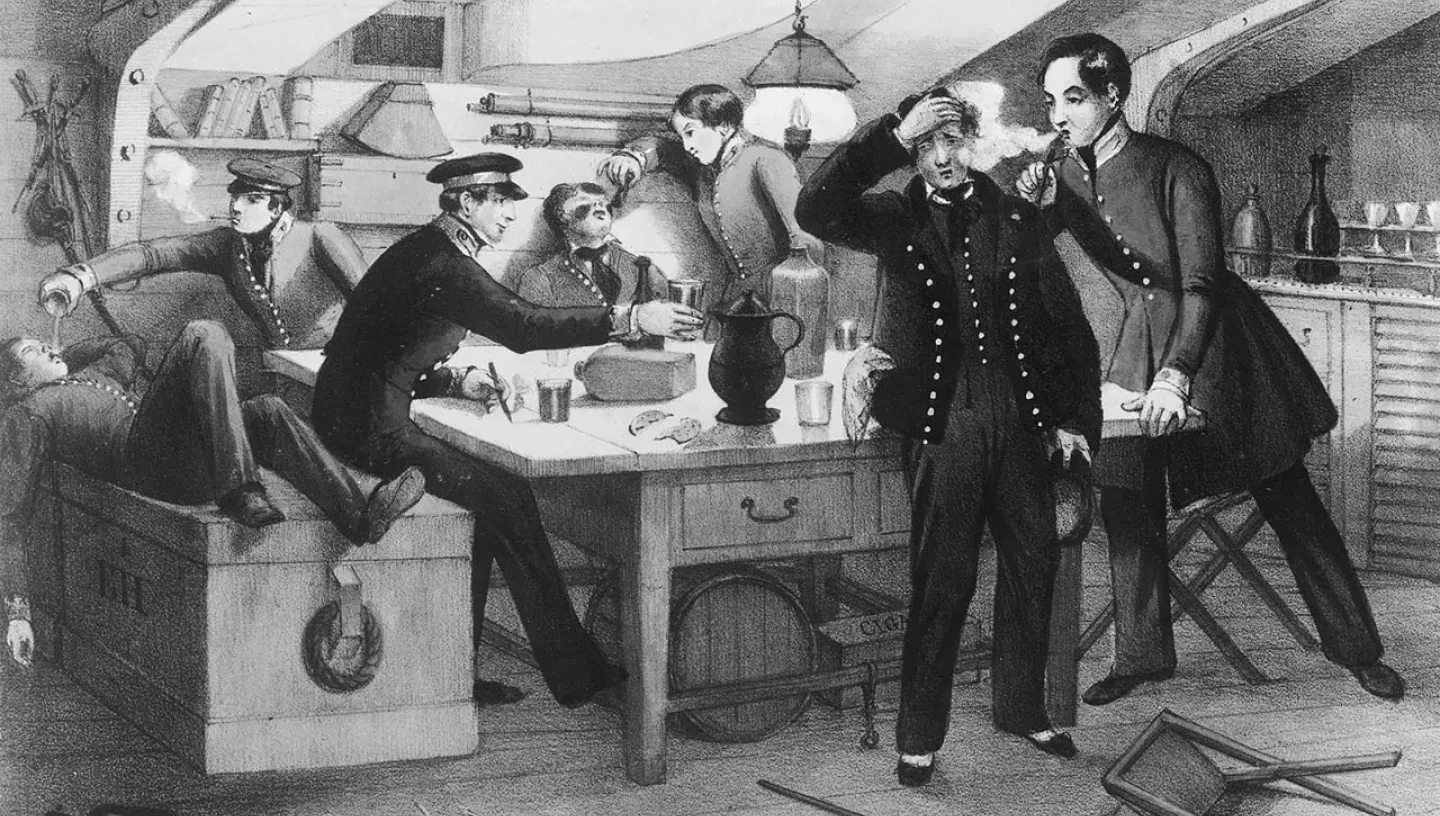

What was eaten at sea?

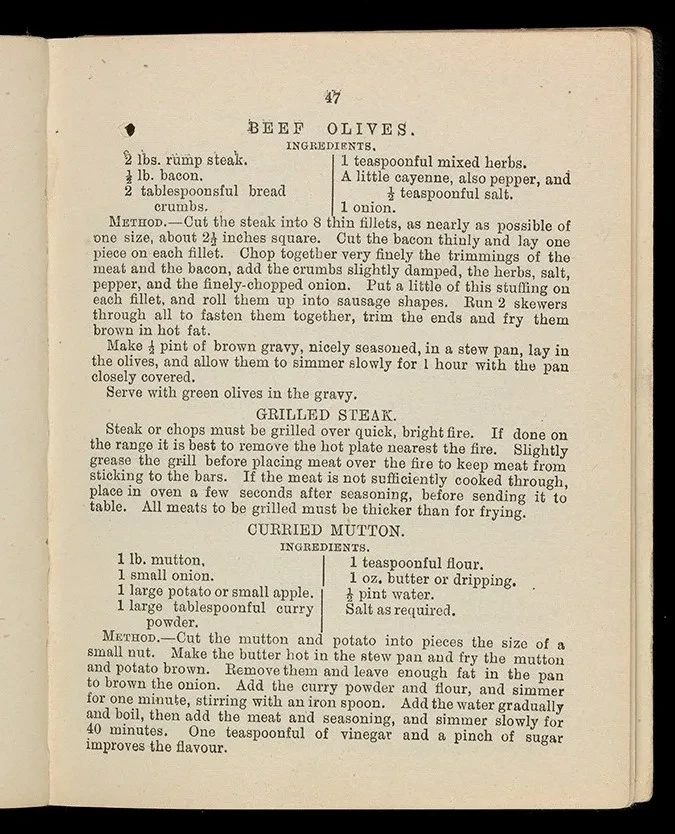

The book begins by describing different cooking methods, including roasting, baking, boiling, stewing and steaming. It also describes how to corn beef, cure ham, pickle meats and preserve eggs. The latter is achieved by coating the eggshells in mutton suet or applying to them 'a good coating of glue, thick gum, or varnish'.

So what does the book reveal about the types of meals eaten on board Britain’s ships? Well, in some cases the dishes are familiar to us today. Tomato soup, fish cakes, roast beef, toad in the hole, Bakewell pudding, and blancmange were all on the menu, although we might struggle to recognize the toad in the hole as it was made with kidneys and cold mutton rather than sausages.

Less familiar are the recipes for sheep’s tongues in aspic, sheep’s head broth and bullock’s heart, although these may well have been more familiar to everyone (not just seamen) in those days.

Also included are recipes for various curries. Whilst not an established part of the British diet at this time, curry had entered British cuisine by the 18th century. The curries featured here used curry powder to flavour chicken, mutton (tinned or fresh) or salt beef – so again there is the sense of the familiar mixed with the unfamiliar.

Likewise, the tomato soup was not a vegetarian option as it contained dripping (fat melted from roasted meat, then cooled). Not all tomato soup today is vegetarian either, as it can contain meat stock, but dripping is in general a less popular cooking ingredient now than it was in years gone by.

Recognition for ships’ cooks

The book’s publication came at a timely moment when the importance of ships’ cooks was beginning to be recognized. The following decade saw the introduction of certificates of competency for ships’ cooks, meaning they had to be formally qualified. In effect, this indicated that their skills were formally recognized and that their role had been professionalized.

Ellen Mann and Alexander Quinlan remained in the Liverpool area and died within a few months of each other. This little book is a memorial to their joint endeavour and a spyhole into what was cooked at sea.

I would like to thank Dr Jo Stanley for some of the biographical information about Ellen Mann.