Did the polluted waters of the Thames contribute to Britain's worst inland waterway tragedy?

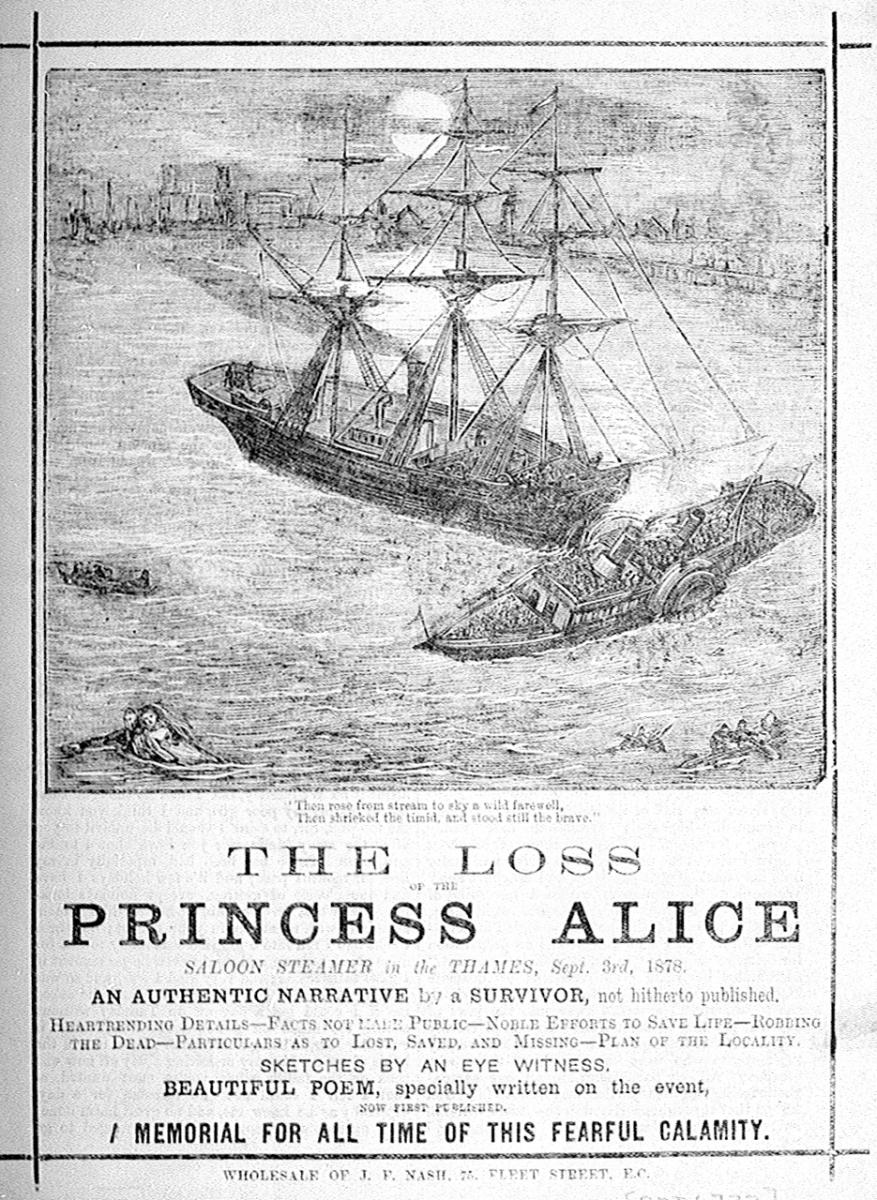

On the evening of Tuesday 3 September 1878, the Princess Alice paddle steamer was making her way up the Thames on her return journey from Sheerness to London.

The weather had been fine and her passengers had enjoyed a day’s pleasure trip to the Kent coast, a popular pastime at this period. Some children were asleep, the band was playing on the main deck, and, near the paddle box, a couple were arguing.

Some time between 7.20 and 7.45pm (accounts vary), when the Princess Alice had rounded Tripcock Point and entered Gallions Reach, passengers saw a large vessel, the Bywell Castle, loom close. They heard William Grinstead, the Princess Alice’s master, call ‘Ease her’, ‘Stop her’, ‘Where are you coming to? Good, God, where are you coming to?’

On board the Bywell Castle, Christopher Dix, her pilot, said, ‘My God, that man is starboarding his helm. Stop her. Hard a-port. Reverse the engines full speed.’

Sadly, this action was too late to avert disaster.

The vessels collided and the Bywell Castle hit the Princess Alice near her starboard paddle box.

There were screams on board the paddle steamer and passengers stampeded towards the gangways. Steam billowed from the gash in the Princess Alice’s side. The vessels drifted together for a short distance, then the Princess Alice broke in two and sank, breaking free of the Bywell Castle, which, according to one eyewitness, passed right over her.

In an instant, the water was heaving with people crying and shouting.

The Bywell Castle lowered her boats, lifebuoys and ropes. Some of the passengers in the water sank beneath the surface and drowned. Some were picked up by rowing boats, and some held onto the ropes let down from the Bywell Castle.

It is thought that the crew of the Bywell Castle saved around 35 people using the ship and around 28 using the boats. Thomas Harrison, the Bywell Castle’s master, testified that the cries and struggles from those in the water had ceased after ten minutes and that the water then contained bodies and debris.

The water in this stretch of the Thames was foul. One survivor, Mr Huddart, said later: ‘I noticed something very peculiar in the water. Both the taste and smell were something dreadful, something that I could not describe – having been down to the bottom and having rose again with my mouth full of it I could give a very good picture of it – it was the most horrid water I ever tasted and the smell was also equally bad.’

No wonder: the water was full of sewage from the northern and southern sewers, which discharged waste into nearby Barking Reach.

Some survivors were brought ashore at Beckton gasworks, a few more in London and others at Erith, with some being conveyed to the Plumstead Workhouse Infirmary. Space also had to be found for the bodies of those who had died. Nineteen of them were laid in the boardroom of the London Steamboat Company (the owners of the Princess Alice), and 28 lay in the Town Hall, including the wife of the Princess Alice’s manager and their four children. The Princess Alice’s master William Grinstead had gone down with the steamer.

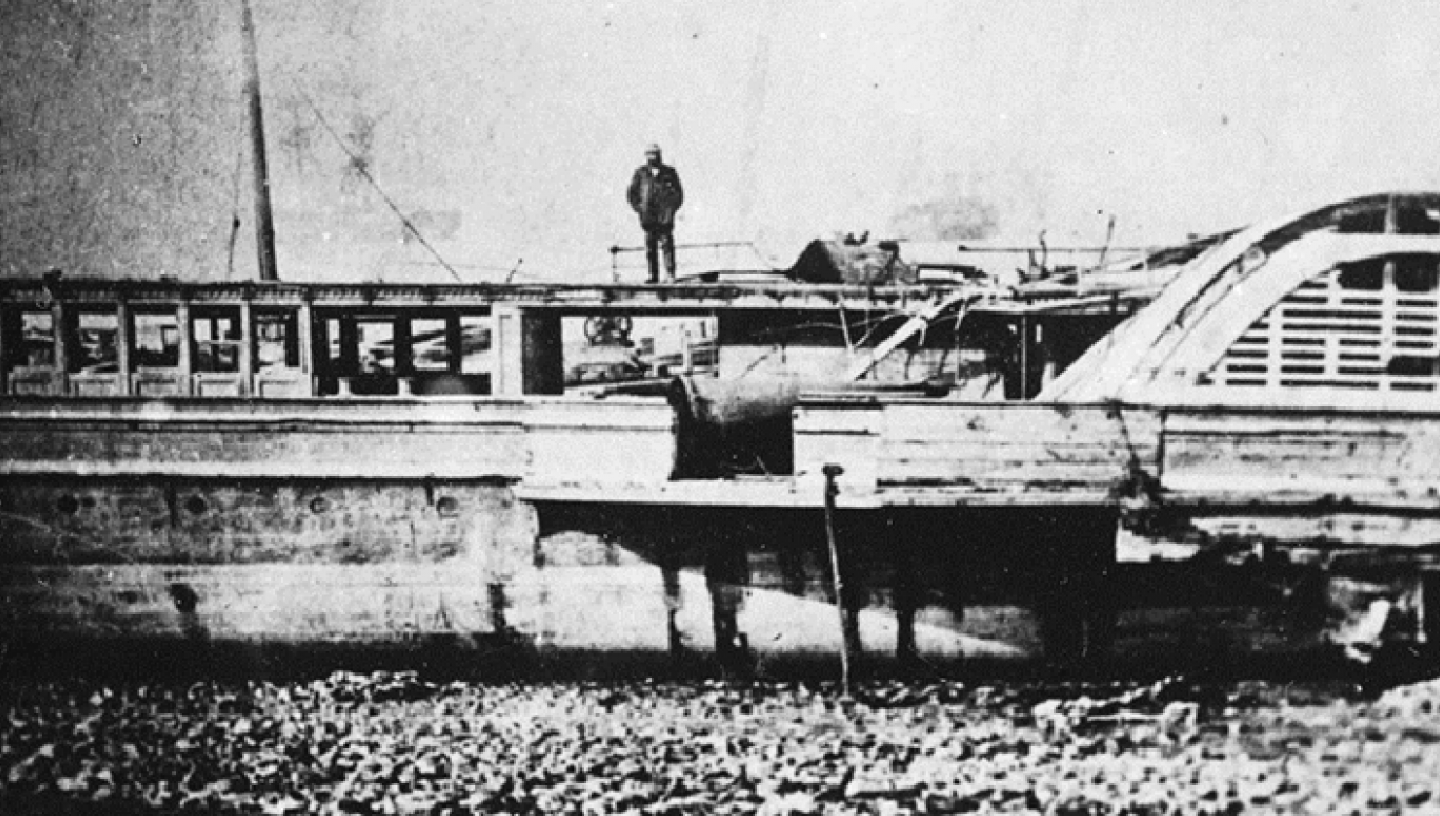

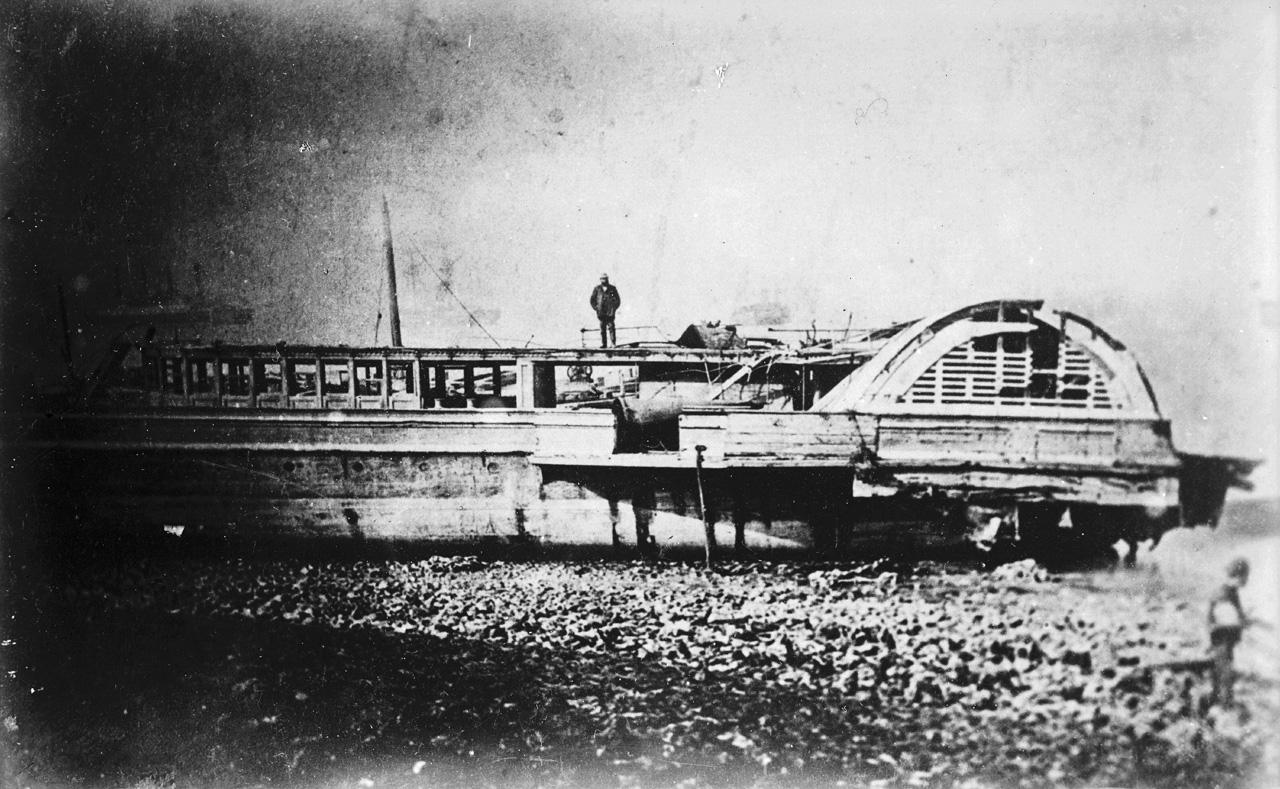

The wreck of the Princess Alice broke into three: the forepart, afterpart and boilers. A diver descended into the fetid water, trying, by touch, to make out what was there. He reported that bodies appeared to be filling the vessel’s cabins. They were in a standing position, crammed around the exit points, presumably in an effort to escape.

On 7 September, the forepart of the Princess Alice was beached and removed. By a twist of fate, whilst this was in progress, the Bywell Castle passed by en route to the sea.

The exact number of passengers on board the Princess Alice during that fatal voyage is unknown, as is the number lost, but it is thought that around 640 people drowned, making this Britain’s worst inland waterway disaster.

Both an inquest and a Board of Trade inquiry were held. A majority verdict by the inquest jury apportioned blame to both vessels.

The Bywell Castle, it said, had contributed to the collision by not acting quickly enough to ease, stop and reverse her engines, and ‘the Princess Alice contributed to the collision by not stopping and going astern’. They also expressed the opinion that there should be ‘proper and stringent rules and regulations [...] laid down for all stream navigation on the River Thames.’

The Board of Trade inquiry blamed the Princess Alice, finding that she had breached the Board of Trade Regulations and the Regulations of the Thames Conservancy Board, 1872. These required a vessel to port her helm if she came end on to another vessel travelling in the opposite direction. It also said the Thames Conservancy Board should better publicise the rules of the road.

By a further twist of fate, five years after the disaster, in 1883, the Bywell Castle herself disappeared, some time after being sighted off the Portuguese coast.

Object in focus

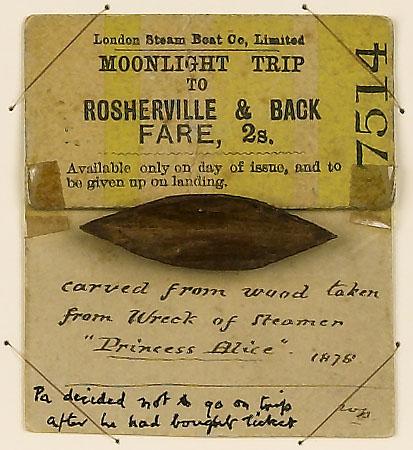

This is a ticket for the ‘Moonlight Trip’ to Gravesend on the Bywell Castle, the ship that collided with the Princess Alice. The small boat attached is carved from a piece of wood taken from the wreck. A note added later, apparently written by one of the ticket holder's children, says that ‘Pa decided not to go on trip after he had bought ticket’. A lucky escape…

If you would like to find out more about the Princess Alice disaster, the Caird Library and Archive have a number of items which could help in your research, including:

- Lock, Joan. The Princess Alice disaster, London: Robert Hale, 2013 (Library ID: PBH6884)

- Thurston, Gavin. The Great Thames Disaster, London: Allen & Unwin, 1965 (Library ID: PBB4808)

- The disaster was also reported in the newspapers of the time, including The Illustrated London News.