The turbulent years of the First World War witnessed a myriad of human experiences, among which the stories of British prisoners of war (POWs) stand as testaments to resilience, endurance, and the human spirit.

Capture

This blog embarks on a journey through two distinct camps where British POWs were interned: Groningen Camp in the neutral Netherlands and Doberitz Camp near Berlin, Germany. By delving into primary sources from the Caird Library and Archive, we illuminate the stark contrasts in conditions, treatment, and survival strategies faced by these POWs.

The narrative begins amidst the chaos of the Siege of Antwerp, a pivotal moment in the early stages of the First World War. The Royal Naval Division, composed of naval reservists, found themselves engulfed in the conflict. Though some died in the failed Siege of Antwerp, the British troops who retreated found a very varied fate. Some escaped on foot and by rail. One large group of over 1500 were interned in Holland, at Groningen Camp, after a march north eastward while over 900 British were captured and subsequently interned by Germans in camps such as Doberitz.

Groningen Camp in the neutral Netherlands emerged as a haven amidst the turmoil of war, treating British officers captured during the siege with compassion and respect. In contrast, Doberitz Camp near Berlin became a symbol of harsh captivity for many British POWs, where the rigors of war were compounded by the harsh treatment of their captors.

Captivity: Groningen

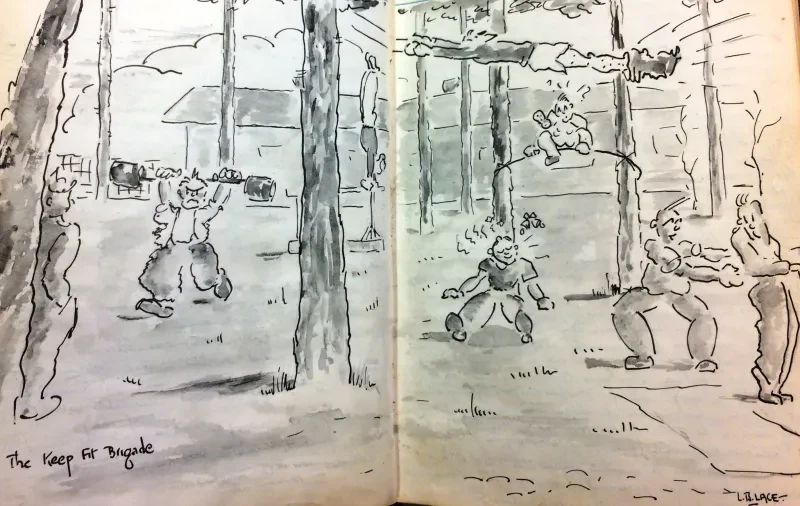

MSS/75/073 contains issues of ‘The Camp Magazine’, First Naval Brigade, which provides invaluable insights into the daily lives of British POWs at Groningen. These magazines offer a fascinating glimpse into the camaraderie, humour, and resilience that sustained them during their internment.

In one magazine they describe the recent loss of a colleague, though they don’t go into detail of what he died from. They also discuss the outbreak of smallpox in the south which led the authorities to safeguard the health of the brigade by vaccination noting that, 'Although we are constantly hearing expressions of remorse from the tender-armed majority, we must yet bow to superior knowledge, recognizing that prevention is better than cure.'

Although we are constantly hearing expressions of remorse from the tender-armed majority, we must yet bow to superior knowledge, recognizing that prevention is better than cure.

MSS/75/073 also contains photographs and postcards sent and received by Ernest Edwin Russell while interned at Groningen, offering a tangible connection to the past and the treatment of the POWs there. It reveals that Ernest was allowed to marry at the camp to Daisy Champion from Hempstead. She was allowed to stay there for three months. It is also noted that some people were allowed home for leave or medical emergencies as long as they returned to camp afterwards. It is recorded within Ernest’s records that he was sent to Chatham Naval Hospital for an appendix operation in 1916 before being sent back to Groningen.

Captivity: Doberitz

In stark contrast to the relative tranquillity of Groningen, Doberitz Camp near Berlin presented a harsh and unforgiving environment for British POWs. Life at Doberitz was marked by overcrowding, inadequate provisions, and strict discipline from German guards.

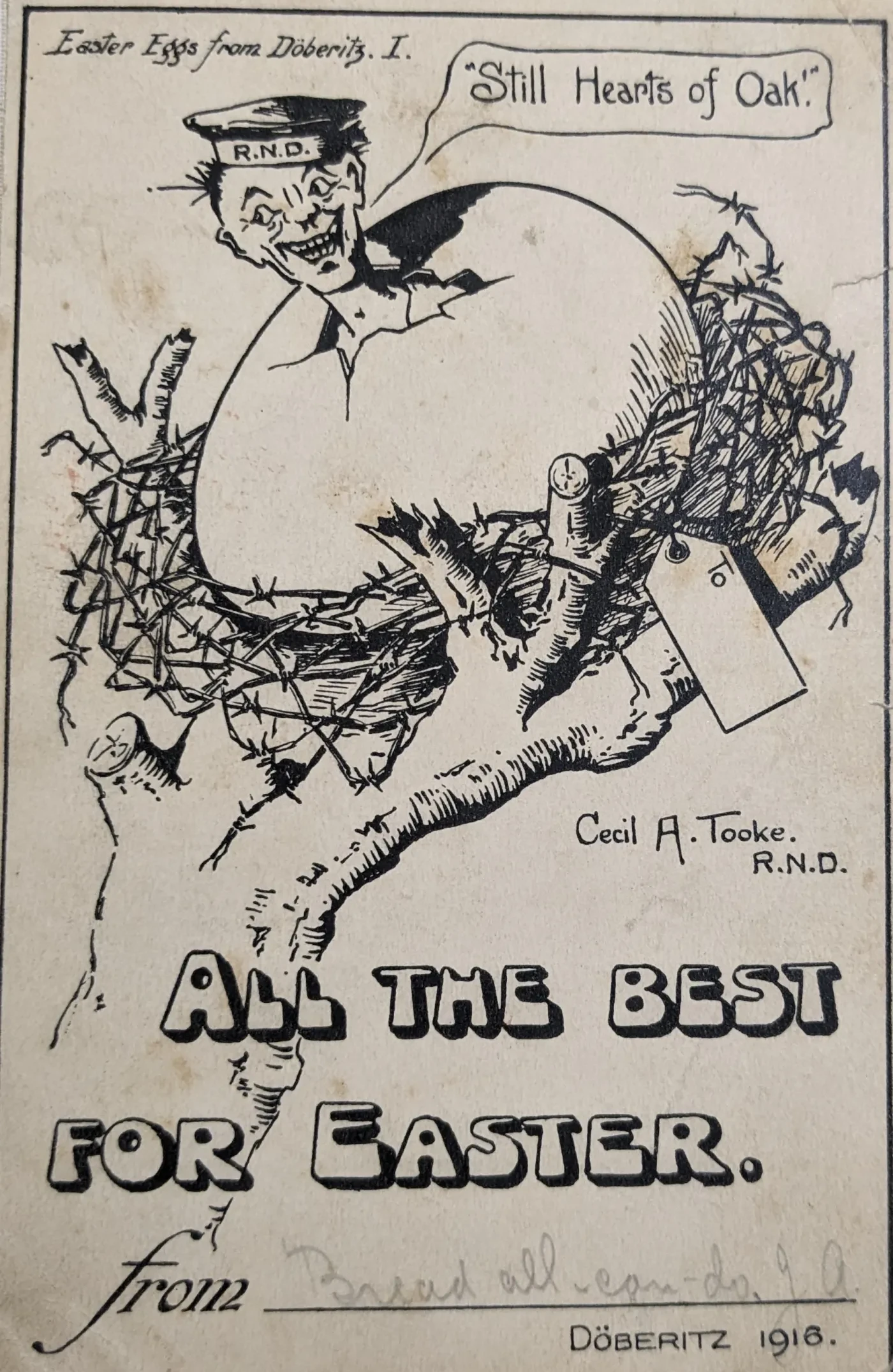

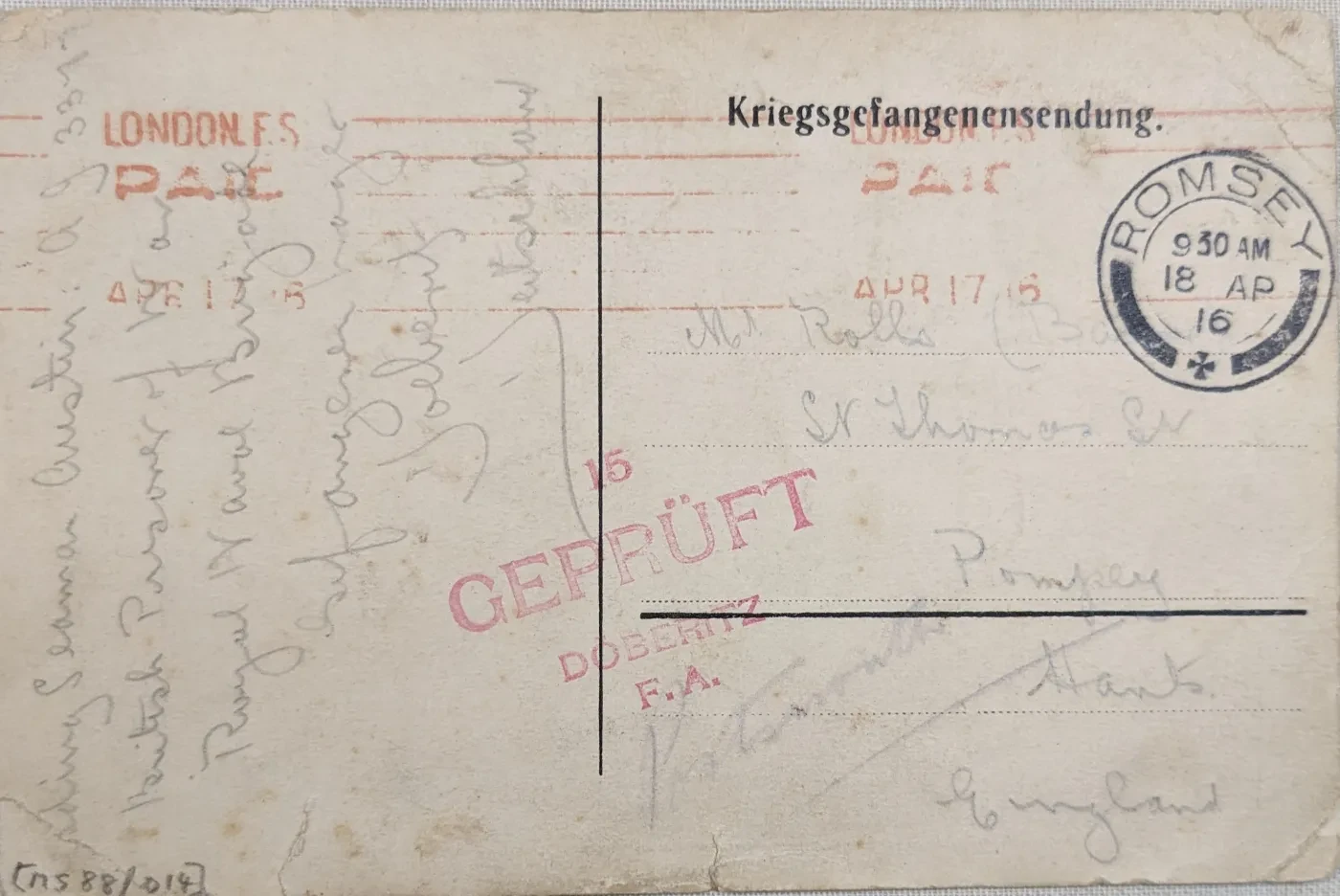

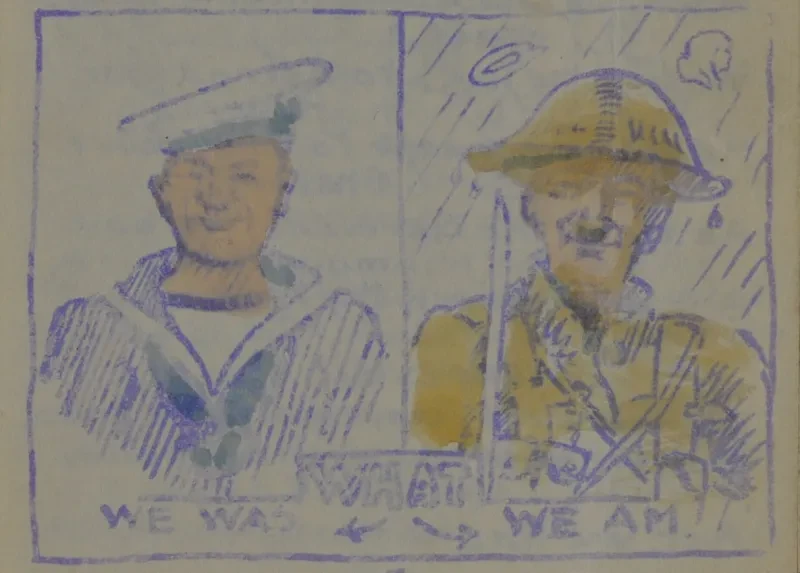

Among the artefact sources from the archives, MSS/88/014 is an Easter postcard dated April 1916 sent by Leading Seaman Arthur J. Austin, a British prisoner of war from the Doberitz POW camp. Arthur was originally part of the Hawke Naval Brigade and remained in Doberitz from 1914 to 1919.

The artist is Cecil Arthur Tooke, a Royal Navy reservist. He became an art editor of the Doberitz Gazette and produced a series of eight postcards for the prisoners to write home.

Though Doberitz was one of the larger camps in Germany the overcrowding was made worse when more POWs were sent there.

The camp made world news when it was reported that Private William Lonsdale from the Second Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding) had been sentenced to death for punching a German guard. An appeal was successful after world press got involved and his sentence was reduced to 15 years which was eventually pardoned. This alone highlights the difference in treatment that POWs received depending on which camp they were sent to.

Despite these challenges, British POWs at both camps displayed remarkable resilience and resourcefulness, forming tight-knit communities, engaging in clandestine resistance activities, and relying on solidarity to endure captivity.