Traditionally, Jonathan Hulls had often been credited as the first person to conduct practical experiments involving steam-powered vessels. Why then, is his work not remembered?

by Jon Earle, Library Assistant

Visit the Caird Library and Archive

Jonathan Hulls was born in Gloucestershire in 1699. With a natural gift for mechanics he began his professional life making and repairing clocks. He cultivated a reputation in his younger years for being thoughtful and studious, and it was during this period that he would first think of the idea that he would become synonymous with. Hulls’s patent published in 1737 and entitled ‘A description and draught of a new-invented machine for carrying vessels or ships out of or into any harbour, port or river, against wind and tide or in a calm’, is one of the earliest mentions of how steam may be employed in the propulsion of vessels. The Caird Library is lucky to hold an original copy of this patent within our rare book collection (Item ID: PBN3358), which not only provides the specifications on Hulls’s design but also insight into Hulls himself and the hopes he had for his invention.

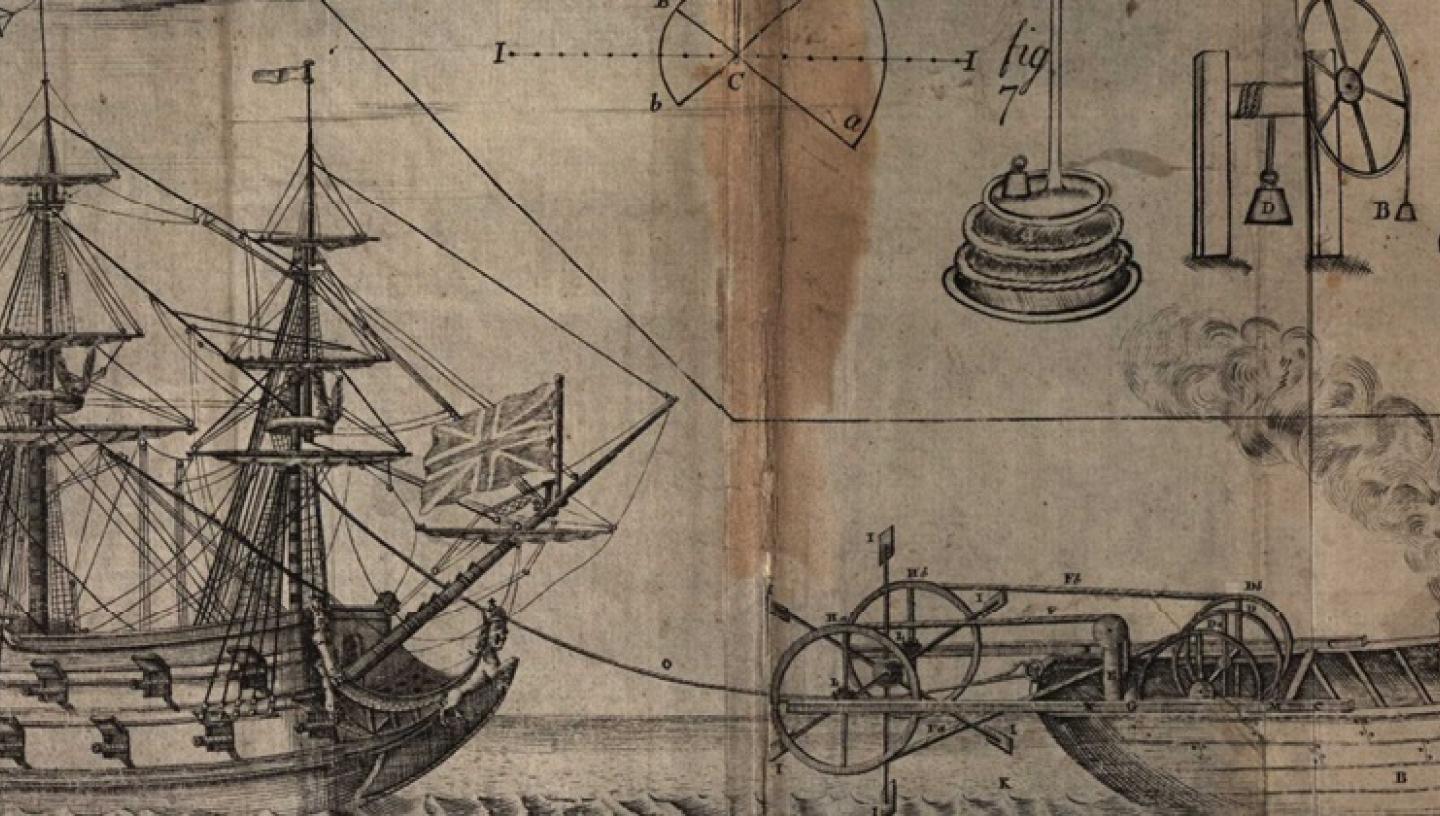

Hulls described his invention as a ‘machine for carrying ships and vessels out of or into any harbour or river against the wind and tide.’ As shown in the design below Hulls intended to employ a smaller stern paddle-wheeled vessel powered by a Newcomen atmospheric engine, to tow the larger vessel. To ensure continuous rotation of the paddle wheels he proposed the use of smaller ratchet wheels driven by ropes from the piston. Hulls also provided a full description of all the intricate mechanisms and a list of advantages for employing a separate towboat rather than using steam to power the larger ship. It is clear that he studied all aspects of this field in great detail and was fiercely proud of what he had accomplished. At the end of his patent, Hulls defiantly responds to several hypothetical questions he foresaw being asked concerning the usefulness of his invention. He defended his creation against imagined criticisms that it would be too small to tow a much larger vessel, and that the force of the water would damage parts of it.

One of the most interesting aspects of Hulls’s story is the contemporary reaction to his patent. Before he had even released his work to the public this was clearly something that troubled Hulls as he stated the following in the preface to his patent:

‘There is one great hardship lies too commonly upon those who propose to advance some new, tho’Useful, Scheme for the publick Benefit. The World abounding more in rash Censure than in a candid and unprejudiced Estimation of Things; if a person does not Answer their expectation in every Point, instead of Friendly Treatment for his good Intentions he too often meets with Ridicule and Contempt.’

Unfortunately for Hulls, ridicule and contempt may have been preferable to the reaction he did receive. He was utterly unable to interest the public in his invention and generally received a complete lack of attention for his work. This failure led to his only benefactor abandoning the project, unwilling to risk any further outlay. He was so quickly forgotten by the scientific community, that just forty years later, a part of his design was patented by the far more well-known James Watts, who clearly had no knowledge of Hulls’s prior work. Jonathan Hulls did not continue his work in the field of steam power and the only other patent he ever applied for was in 1753, for an ingenious apparatus to detect counterfeit coins. He would die in poverty just five years later at his house in Campden, Gloucestershire, where he spent the majority of his adult life. Seemingly only remembered in the following doggerel allegedly spoken long after Hulls’s death in his hometown:

‘Jonathan Hulls,

With his patent skulls,

Invented a machine

To go against wind and stream;

But he, being an ass,

Couldn’t bring it to pass,

And so was ashamed to be seen.’

Notes and Queries, First Series, Vol. III

Hulls would have been happy to know that whilst he did not receive praise for his achievements during his lifetime, many 19th-century figures looked back favourably upon Hulls’s work including Sir John Barrow, who is the author of the quote at the beginning of this blog. Indeed, historians from this period have generally talked of his work in a positive light, whilst not necessarily going as far as Barrow. George Preble in his work A chronological history of the origin and development of Steam Navigation, defended Hulls and referred to him as: ‘the first inventor of an ingenious and practicable mechanism for propelling vessels by a condensing steam-engine and by paddle-wheels’. This view is echoed by a number of other historians, with some suggesting portions of his work inspired William Symington, the builder of the first practical steamboat; whilst others go further with their praise, like Barrow, bestowing upon Hulls the title of inventor of the steam vessel.

Why then is Jonathan Hulls not remembered for his role in the development of steam-powered vessels? Whilst more modern historians have been less kind to Hulls’s invention, with some suggesting his design never would have worked; the most significant reason was referenced by the man himself:

‘I hope that … they will form a judgement of my present Undertaking only from trial.'

Traditionally it had been claimed that he did organize a practical test on the Avon at Evesham, although there is no evidence to support this. Moreover, many feel that had such tests ever been undertaken, history would have remembered them. As Hulls himself said, his invention should be judged based on its performance at trial, but with no practical tests ever conducted, can he truly be remembered as a pioneer of steam power or simply as a man who proposed an idea that others would later act upon with far more success?