This blog looks at an illustrated log recently added to the collection of papers from the naval career of Admiral Sir Watkin Owen Pell. It reveals how a prize crew was shipwrecked and captured on the enemy’s coast during the Napoleonic Wars.

The background to this log is Pell’s service as first lieutenant on the frigate HMS Mercury during an outbreak of prize-taking in the Adriatic. Much of the earlier British naval war effort against France had focused on a blockade in the western Mediterranean theatre.

By the year 1809 however, the kingdom of Naples had become a French puppet state, and then a series of military defeats suffered by Austria resulted in both sides of the Adriatic falling under French control.

Fears of a further expansion of Napoleon’s empire resulted in British warships including the Mercury being sent to disrupt the enemy’s trade and shipbuilding capacity in the Adriatic. During this campaign, Pell directed boat attacks that succeeded in the taking of two prizes, the gunboat Leda from Rovigno on 1 April 1809, and the schooner Pugliese from Barletta on 7 September 1809.

The actions were later celebrated in oil paintings by William J. Huggins, owned by the Pell family (RMG references: BHC0589 and BHC0592).

Reports of the gallantry of 7 September 1809 highlighted the fact that the Pugliese was captured without any casualties or injuries on the British side, despite the operation being carried out within the range of much enemy musketry, a castle mounting eight guns, and two French privateers.

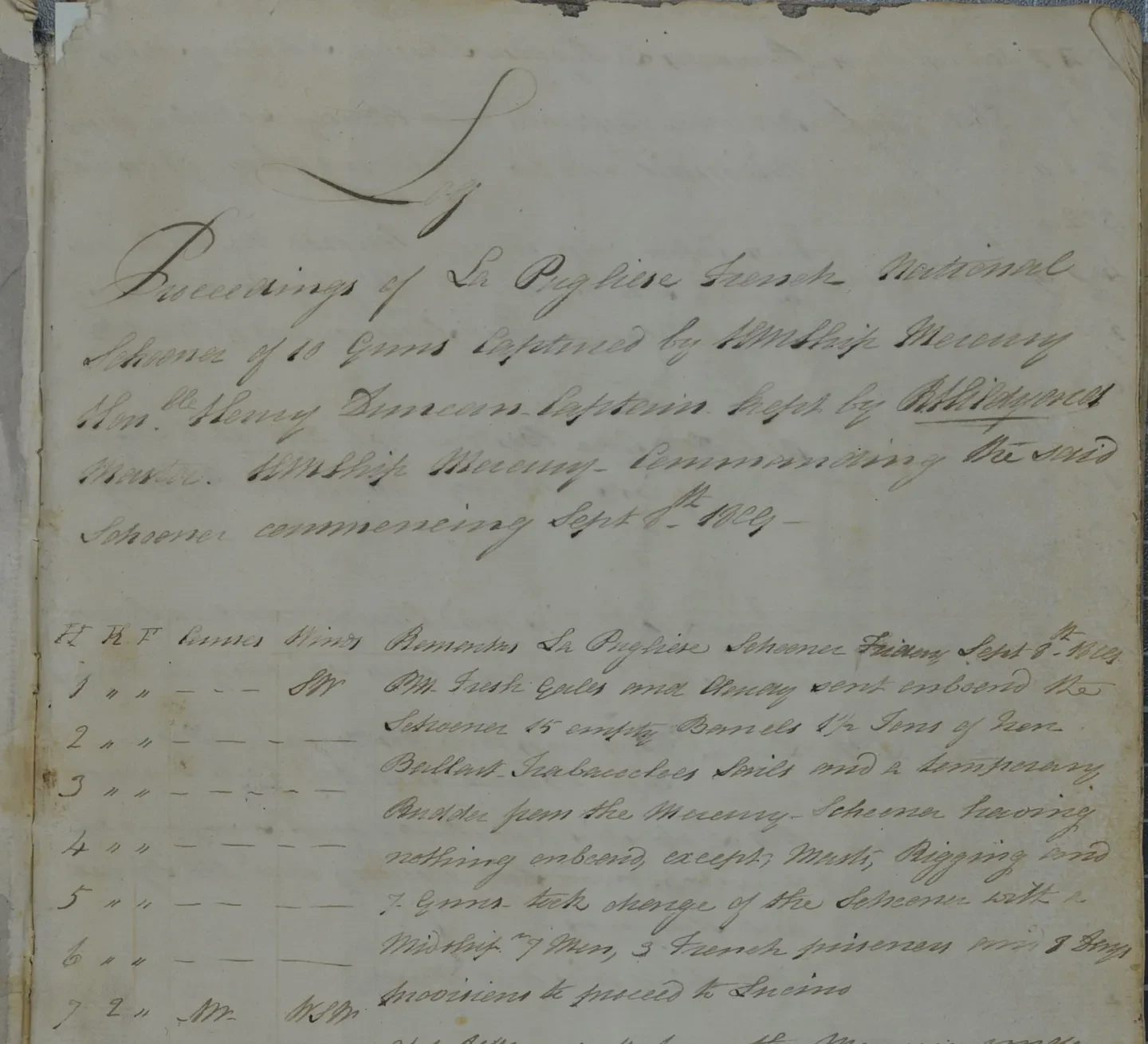

On the following day, Richard Hildyard, master of the Mercury, was put in charge of the Pugliese and commenced his log. It provides us with a sequel very different in tone to the story of Pell’s success at Barletta.

The log tells us how the crew of the Pugliese, consisting of Hildyard, two midshipmen and seven seamen, had orders to follow the Mercury towards the island of Lussin (now Lošinj). However, their progress was beset with problems. Finding their rudder to be defective, they had to put into Lissa (now Vis), an island with a safe anchorage that became a strategic base for the British navy.

While waiting for repairs and supplies, Hildyard was reluctantly drawn into disputes arising from the behaviour of Maltese and Sicilian privateers, who were preying on local traffic in the Adriatic.

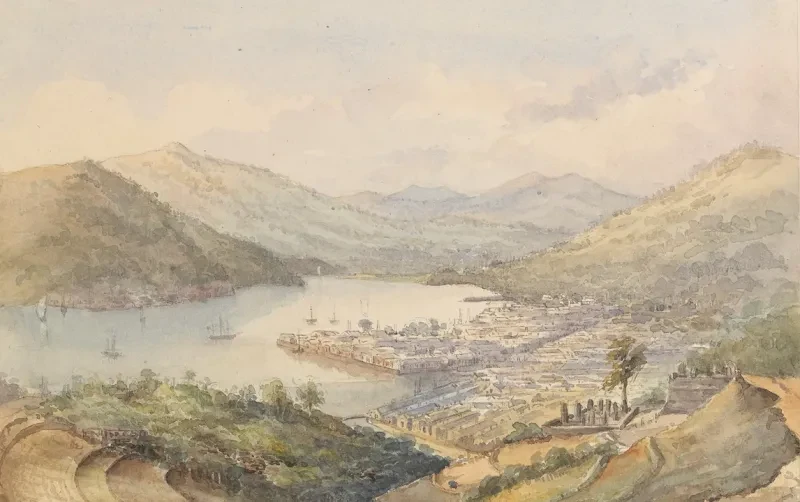

The Pugliese later reached Fiume (now Rijeka), and presumably because that port had fallen under French control, the crew were ordered to follow the Mercury to Malta. However, after being hampered by strong gales and taking on a lot of water, their situation became perilous.

Exhausted from the fatigue of constantly bailing out water from the hold, their only hope lay in reaching the safety of the British squadron at Corfu.

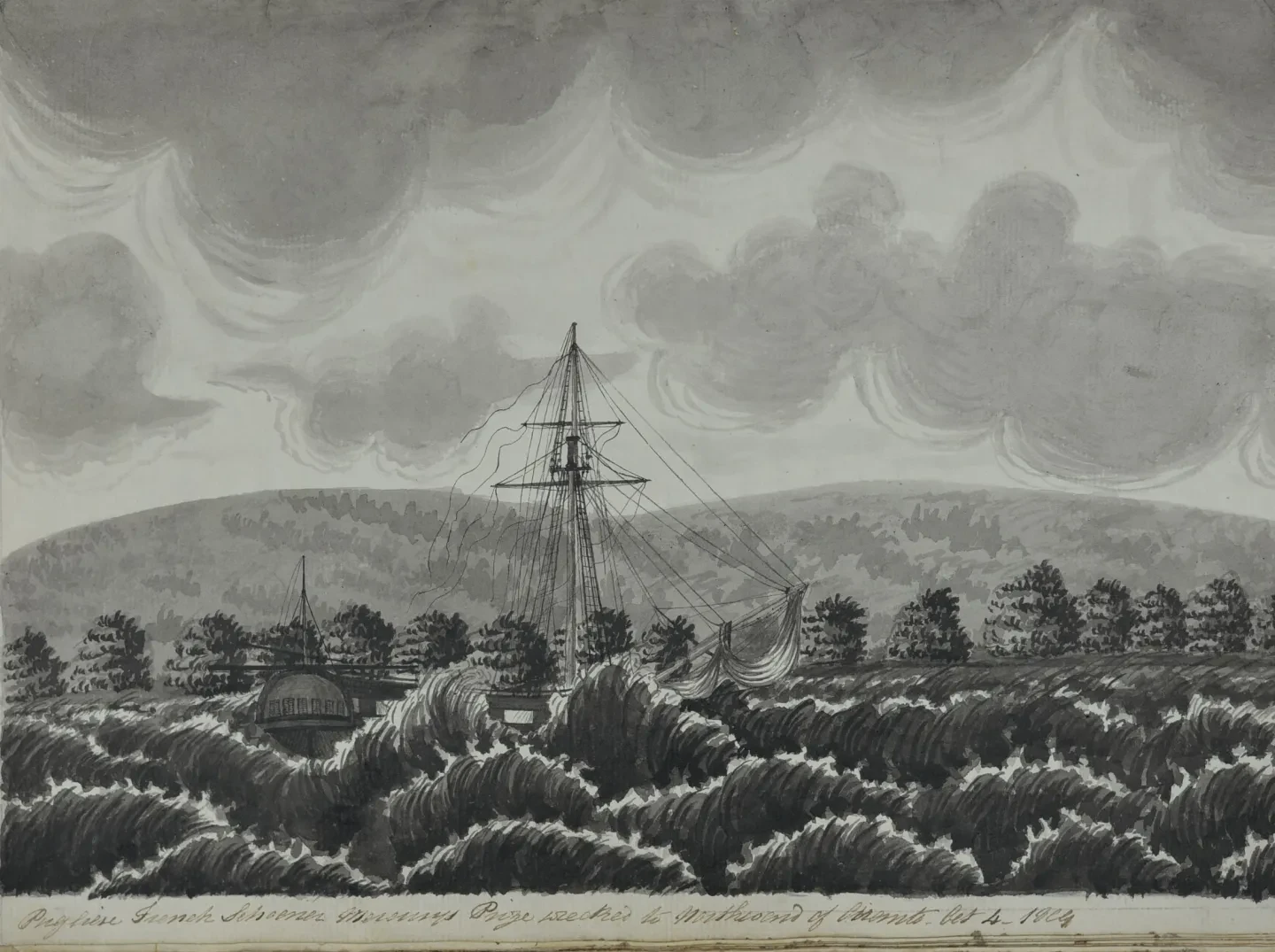

On 4 October the schooner went aground off the Italian mainland, and the following day drifted closer to the shore.

The crew abandoned the Pugliese on a beach to the north of San Cataldo, near the city of Lecce, hoping to find another boat to attempt an escape.

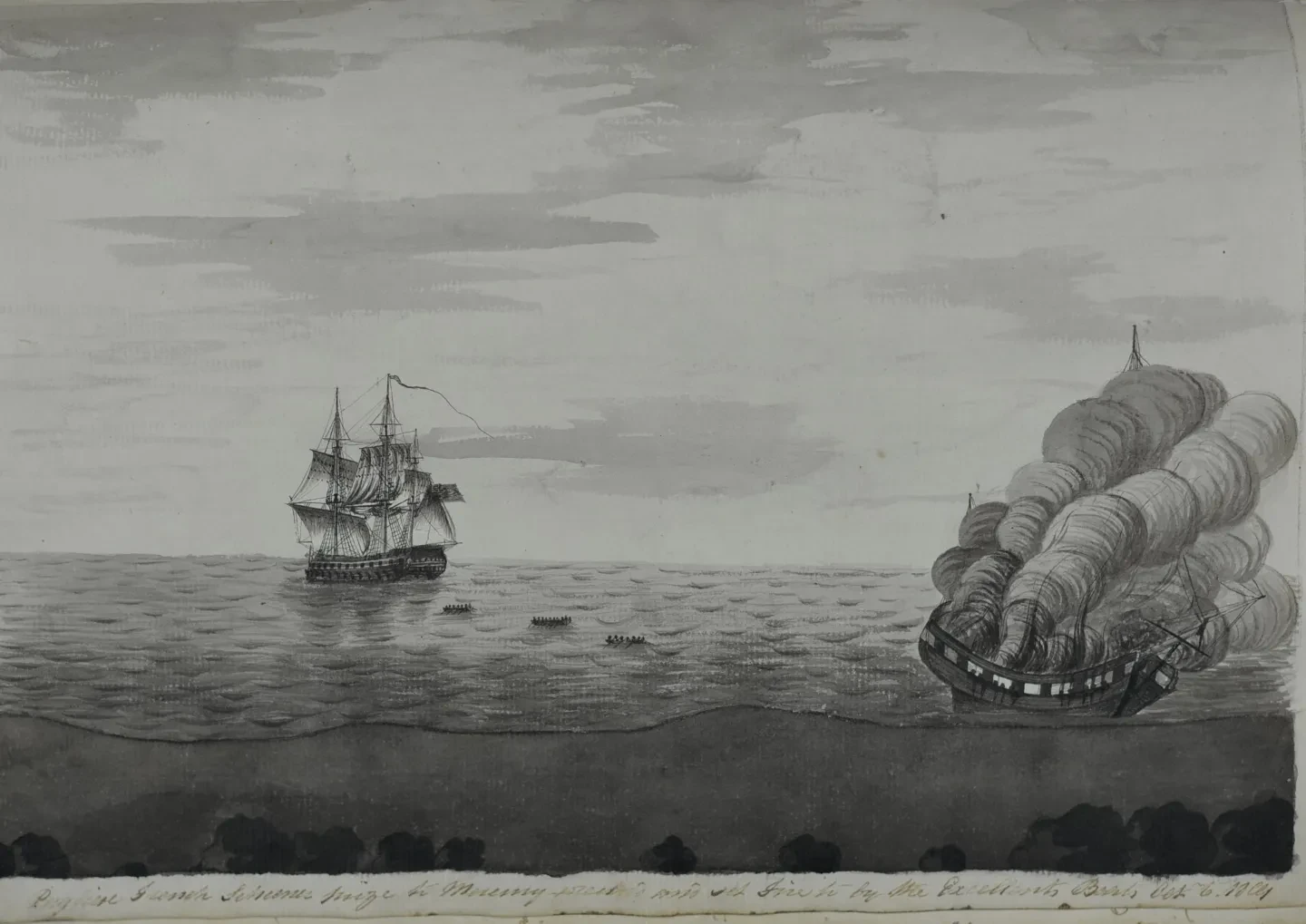

However, they were soon outnumbered by enemy troops from the local garrison and had to give themselves up as prisoners of war. As they were marched off to be put into quarantine at Brindisi, they observed boats from HMS Excellent, sent to destroy the Pugliese by setting fire to her.

Despite initial promises to the contrary, the crew found themselves closely confined and indifferently treated at a castle in Brindisi. Luckily, they were able to purchase some necessities from sympathetic locals and so recover from their shipwreck ordeal.

From early November 1809 onwards, Hildyard wrote letters to the local military commander and minister of war to petition for better treatment. Subsequently, the prisoners were held instead at Taranto, and then by Christmas of 1809 they were at Castle Carmine in Naples. Here they could rely on the interest of those inhabitants of the city who had relations among French officers held as prisoners of war in Malta.

Ultimately, there was the prospect of being sent to Sicily on parole. At this time, Sicily was occupied by British forces, so British prisoners sent there under a flag of truce could be exchanged for French prisoners sent from Malta.

In March 1810 Hildyard was ordered to leave his crew behind at Naples and embark on a French gunboat for Salerno. After further journeys towards the southern tip of Italy, Hildyard was able to make the crossing to Messina on parole and wait there for a prisoner exchange. Presumably, he regained his freedom soon after 13 May 1810, the date of the last entry in the log of the Pugliese.

We know that Hildyard received a pension for his wounds by an Admiralty order of August 1811. Then his signature in the log PLL/89 can be matched against that shown in a marriage record in the parish of Alkborough, Lincolnshire, from July 1813. In retirement he lived in the Hull area, where local newspapers mention that a musket ball had perforated one of his wrists during his service as a naval officer.

As a master, Hildyard would have been skilled in navigation and seamanship, but his career had been marred by charges of misconduct. The letter ‘R’, signifying run or deserted, was placed against his name in the ship’s book of HMS Pluto in May 1805. Despite Hildyard’s explanation that he had failed to join the ship because of an unrelated legal action, Commander Richard Janverin of the Pluto threatened a court martial.

The ‘R’ was finally removed by Admiralty order in March 1807, following Hildyard’s direct appeal to The Navy Board in January of the same year. His certificate of service can be found in the warrant officers volume ADM 29/1 held at The National Archives (TNA). It appears to state that he was engaged on the Mercury until 29 October 1809, but there are no clues as to how he returned home.

The ordeal of shipwreck and capture told by the log is a counterpoint to those manuscripts and works of art that convey the rewards of prize-taking during the Napoleonic Wars. It gives us insight into the experiences of British prisoners of war, though from the perspective of a warrant officer, who had sufficient status to be given opportunities to petition and regain his freedom.

One of the mysteries that remains is how Hildyard’s log came to be in the possession of the Pell family. We know that it was used by Sarah M. Maude née Pell when she was compiling information for a biography of her father. Perhaps she was making a comparison with the paintings by Huggins when she referred to the pen and ink drawings in Hildyard’s log as ‘scenes most telling but somewhat grotesque’.

Sarah M. Maude’s transcript of the log of the Pugliese can be found in the Pell collection (RMG reference: PLL/82).

A copy of Hildyard’s appeal to have the ‘R’ removed from his service record is enclosed with a letter dated 2 March 1807 in the volume of Navy Board correspondence from 1807 (RMG reference: ADM/B/225).

High Court of Admiralty papers relating to the prize Pugliese captured in 1809 can be found under the reference HCA 32/1814/2735 at The National Archives (TNA).

The British campaign in the Adriatic and in particular its use of the island of Lissa (now Vis) are covered in ‘The British and Vis: War in the Adriatic 1805-15’ by Malcolm Scott Hardy, Archaeopress, 2009.

A record of the marriage of Richard Hildyard and Sarah Sutton in the parish of Alkborough, Lincolnshire, on 22 July 1813 can be found using the Findmypast website.