Letters by the Pan-African civil rights leader and founder of the Black Star Line to retired naval officer Vice-Admiral Sir William Henderson have been unearthed in the Caird Library's archives

Content warning: This blog contains content which may cause distress. Some of the historic language expressed here is considered offensive, and its presence is not an endorsement of the terms. This language has been retained to reflect the historical context of the times.

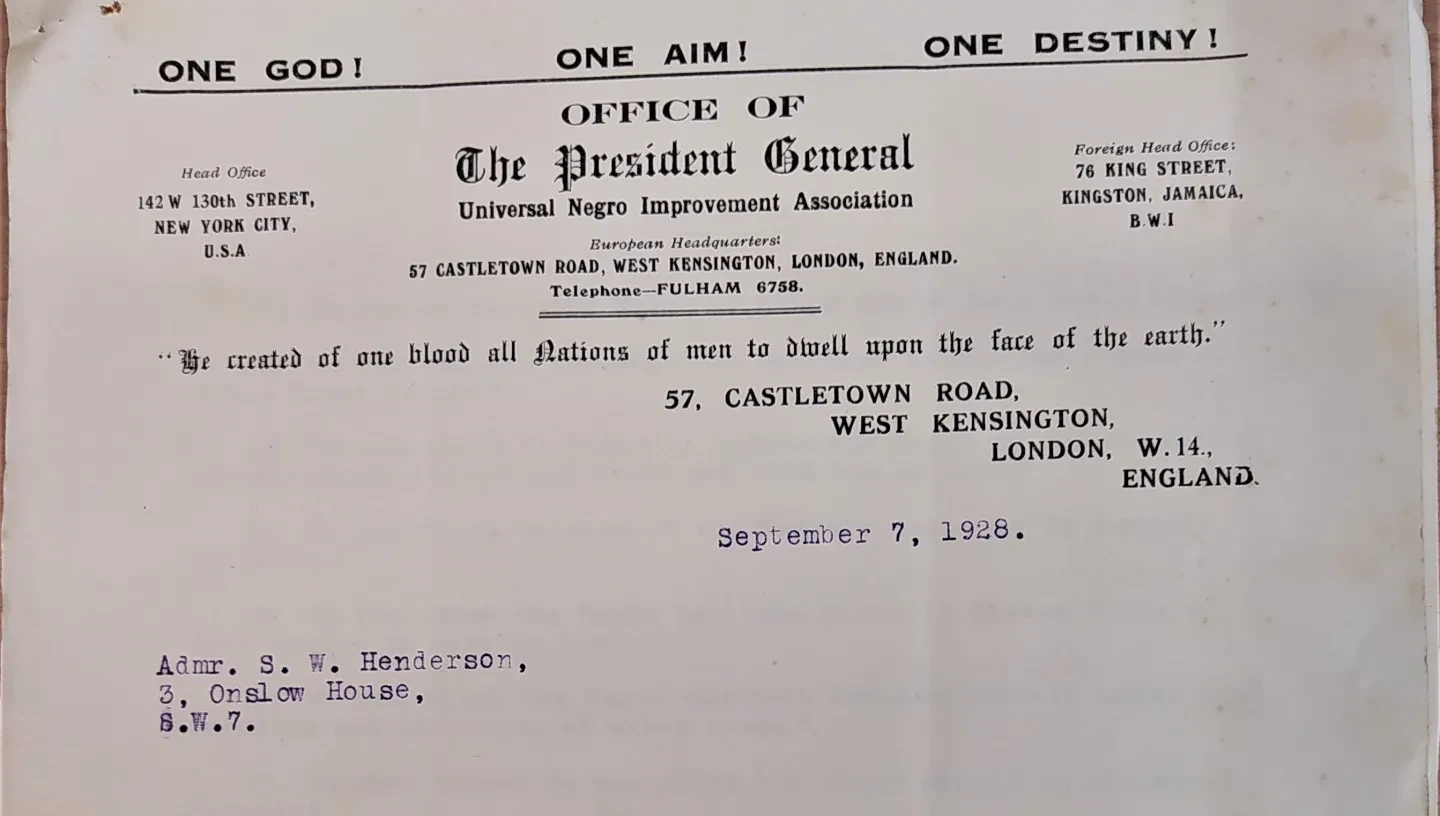

While living in London in 1928, Marcus Garvey, the Pan-African civil rights leader and founder of the Black Star Line, corresponded with retired naval officer Vice-Admiral Sir William Henderson. Here we take a closer look at the letters they exchanged, which were found among Henderson’s collection of personal papers in the archives.

'Hidden' in the archives

Collections will often include a bundle of miscellaneous papers covering various topics, only one or two of which will be highlighted in the catalogue. This can lead to manuscripts of some significance being ‘hidden’ in archives. Such is the case with the personal papers of Vice-Admiral Sir William Henderson (1845–1931), acquired in the 1950s (RMG ID: HEN).

One file of correspondence in the collection, HEN/24, is described as being ‘on a variety of subjects’ with only the proposed Channel Tunnel and the Wembley Tattoo mentioned in the catalogue. While looking for papers on the Channel Tunnel in this file, however, I came across some correspondence between Henderson and Marcus Garvey (1887-1940). The personal papers of a retired British Admiral would probably not be the most obvious place to find material about a Black civil rights activist, and so might certainly be considered worthy of a mention in the catalogue.

Jamaican-born Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in Jamaica in 1914. In 1918, he moved the UNIA's headquarters to New York. In 1928 Garvey, who styled himself the Provisional President of Africa, was living in Castleton Road in Kensington, from where he set up the European headquarters of the UNIA.

It was in his capacity as the UNIA’s President General that he wrote to Admiral Henderson on 7 September 1928, describing it as ‘an organization of Eleven Million Negroes… which represents the interests of the entire black race'. Garvey tells Henderson that he regards him as ‘a representative type of your race’ and asks for his opinion on ‘the efforts we are making to develop ourselves as a people under our own direction, a privilege that is claimed by all the progressive groups of humanity’.

There follows a series of 22 questions that Garvey refers to as a ‘symposium’. The first questions concern the fundamental humanity of Black people, question 1 being ‘Do you believe the Negro or black man to be a human being?’

The questions that follow focus on the impact of colonialism and imperialism on the Black diaspora. It could be argued that the questions are phrased in such a way to encourage a response favourable to Garvey’s own position. For example, question 13 asks ‘Do you think it immoral that the Negro should be tricked, fleeced and robbed out of his lands and other valuables in Africa and America and elsewhere without protest?’ The letter ends with a statement of the aims and objectives of the UNIA.

Included in the file is a draft of Henderson’s replies to Garvey and, as might be expected, Henderson expresses a quite different perspective on colonialism, and some scepticism of Garvey’s grand vision of Black independence.

In response to question 13 Henderson replies: ‘It must be remembered that throughout the history of man the virile races have always displaced the less virile; that it is only quite recently that the higher forms of civilization lately reached, have come to look upon this displacement and the manner in many cases by which it was carried out, as wrong.’

In response to question 19 which asks: ‘When the time comes for the Negro or black man to be repatriated back to their ancestral home, Africa, will you be sympathetic toward the movement, and, if possible, help to make it a reality?’ Henderson replies ‘I should not be unsympathetic could it be proved to me that it was possible. My position is that I think it impractical.’

Henderson also recalls his experience of being Commander at the Jamaica station from 1898–1900, during which time he had ‘a good deal to do with the leading black and coloured people of the island.’ His conclusion was that Jamaica showed that ‘the negro race have a long way to travel before they will be fit to stand alone'.

Garvey wrote again to Henderson on 18 October, thanking him for his replies to the symposium, and asking for his support for a petition presented by the UNIA to the League of Nations on 11 September 1928. This was a follow up to a 1922 UNIA petition, asking for consideration of the plight of people of African descent scattered throughout the world as a consequence of the transatlantic slave trade. The petition called for a United Commonwealth of Black Nations to be established in West Africa.

Garvey asked Henderson to send a note to the League of Nations encouraging them to consider the petition, stating ‘a note of encouragement from our friends to the League may help to bring relief to hundreds of millions of oppressed black people to the world over'. There is no indication in the file of whether or not Henderson did contact the League as requested by Garvey.

I did not find out any further information about Garvey’s symposium, but it is possible that letters between Garvey and other recipients of his 22 questions exist in other archives, for example The National Archives.

Garvey does have a maritime connection. Possibly one of his most well-known exploits was the Black Star Line, the shipping venture launched in 1919 with the aim of promoting international trade between the Black diaspora.

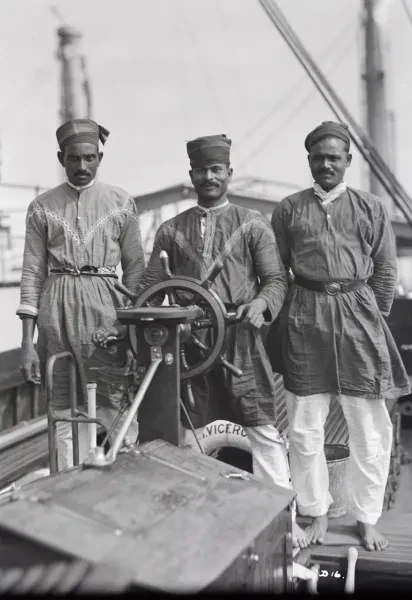

Garvey wanted the Black Star Line fleet to be crewed by Black seamen. Our archives hold the master’s certificate of Joshua Cockburn, who was born in the Bahamas in 1876. Between 1908 and 1915 he served on ships owned by the colonial government of Southern Nigeria, and in 1916 was mentioned in Dispatches for good services in action during the operation in the Cameroons while master of the Trojan. Cockburn was awarded his master’s certificate in 1915 and captained the Black Star Line’s first ship, the British-registered SS Yarmouth.

The Caird Library has a copy of the autobiography of Hugh Mulzac, another Black mariner who was employed by the Black Star Line. He was born in St Vincent in 1886 and gained his master’s licence in 1918 in the US. In his book A star to steer by (RMG ID: PBD6115) Mulzac recalls that when Garvey and Cockburn fell out, Garvey wanted to dismiss Cockburn and make Mulzac master of the Yarmouth, despite Mulzac’s American licence not being valid to command a British-registered ship. Mulzac also describes the large crowds that greeted them across the Caribbean as people flocked to see a ship owned and manned by Black men. But they would call at ports purely to promote the UNIA, lengthening journeys unnecessarily while cargo rotted in the hold.

The Black Star Line was short-lived, folding in 1922 under the weight of mismanagement and corruption. However, it did inspire the eponymous shipping line established in 1957 in the newly-independent Ghana; Kwame Nkrumah, the country's first prime minister, was greatly influenced by Garvey’s writings.

Garvey died in London in 1940, but his remains were returned to his country of birth in 1964 when he was made Jamaica’s first National Hero.