This blog from the Caird Library looks at the history of mental health conditions and how they were viewed in the Navy in the past

Content Warning: This blog contains content which may cause distress. Some of the historic language expressed here is considered offensive, and its presence is not an endorsement of the terms. This language has been retained to reflect the historical context of the times.

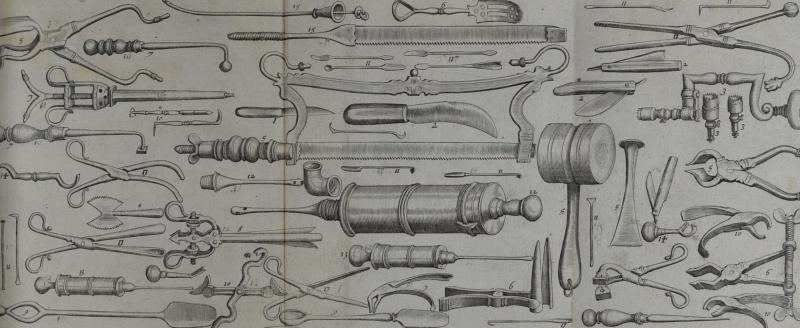

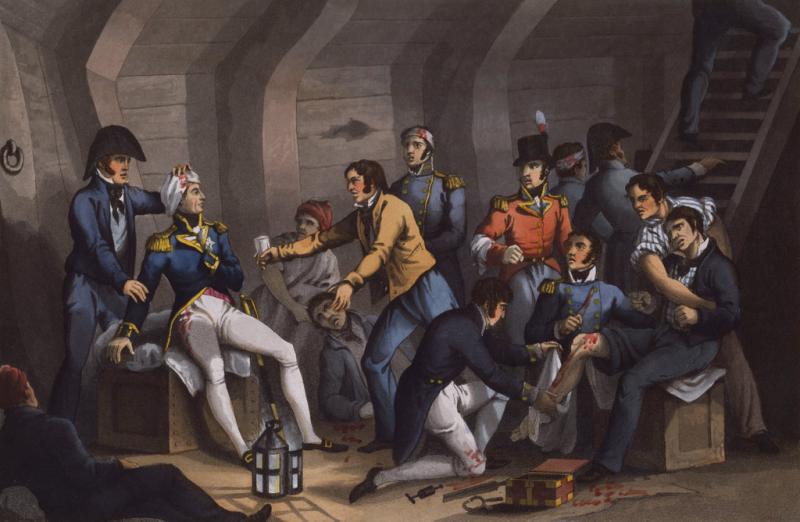

There has never before been such a focus on mental health and wellbeing. It is only in recent years that we have gained an understanding of just how fragile our mental wellbeing is. These days, while analysing our mental health, we take into account such factors as environmental and social pressures, childhood trauma, family history, recent injuries and trauma. In the past, however, most would just be considered unfit for duty and discharged without much information about what caused the ‘breakdown’ in their mental health. Some naval surgeons attributed the cause of what was called ‘insanity or madness’ to head injuries they had sustained. Such is the case of Richard Ryan.

The above certificate is by the surgeon and assistant surgeon of the ordinary at Portsmouth reporting that Richard Ryan is 'frequently afflicted with attacks of mental derangement first occasioned by a severe wound of the back part of his scalp, not received in service, and he is unfit for further service. 4 May 1827'. It is unfortunate that, after Ryan was discharged, there are no further records for him. There were no general retirement pensions for ordinary sailors before 1836 and it is not clear if Ryan received anything for his wound.

It was not only those of low rank who were affected by mental health problems. Experienced officers also suffered under the pressure of their responsibilities. A letter in the Caird Library archive (see below) reveals that a carpenter on the Defiance, Samuel Berkley, was reported by the surgeon of the yard as being 'above five months Insane' without any immediate action being taken. A man who lived with Berkley, a quarterman called Edward Clies, also said 'he has totally lost his senses'. On the back of the letter is a note to install a new carpenter in Berkley's rooms.

While the Navy Board was able to track the medical history of standing officers of low status such as carpenters, it was more concerned with the officers’ records of the ships on which they served than with their medical history. The two letters concerning Ryan and Berkley show that the Navy Board considered that men who were unable to perform their duties had no place in the Navy. Some surgeons were also of the opinion that mental health problems made people ‘unfit for service’, and believed that the emotional and physical pressures of being in the Navy were the cause. Of course, this was true even if the patient was a surgeon.

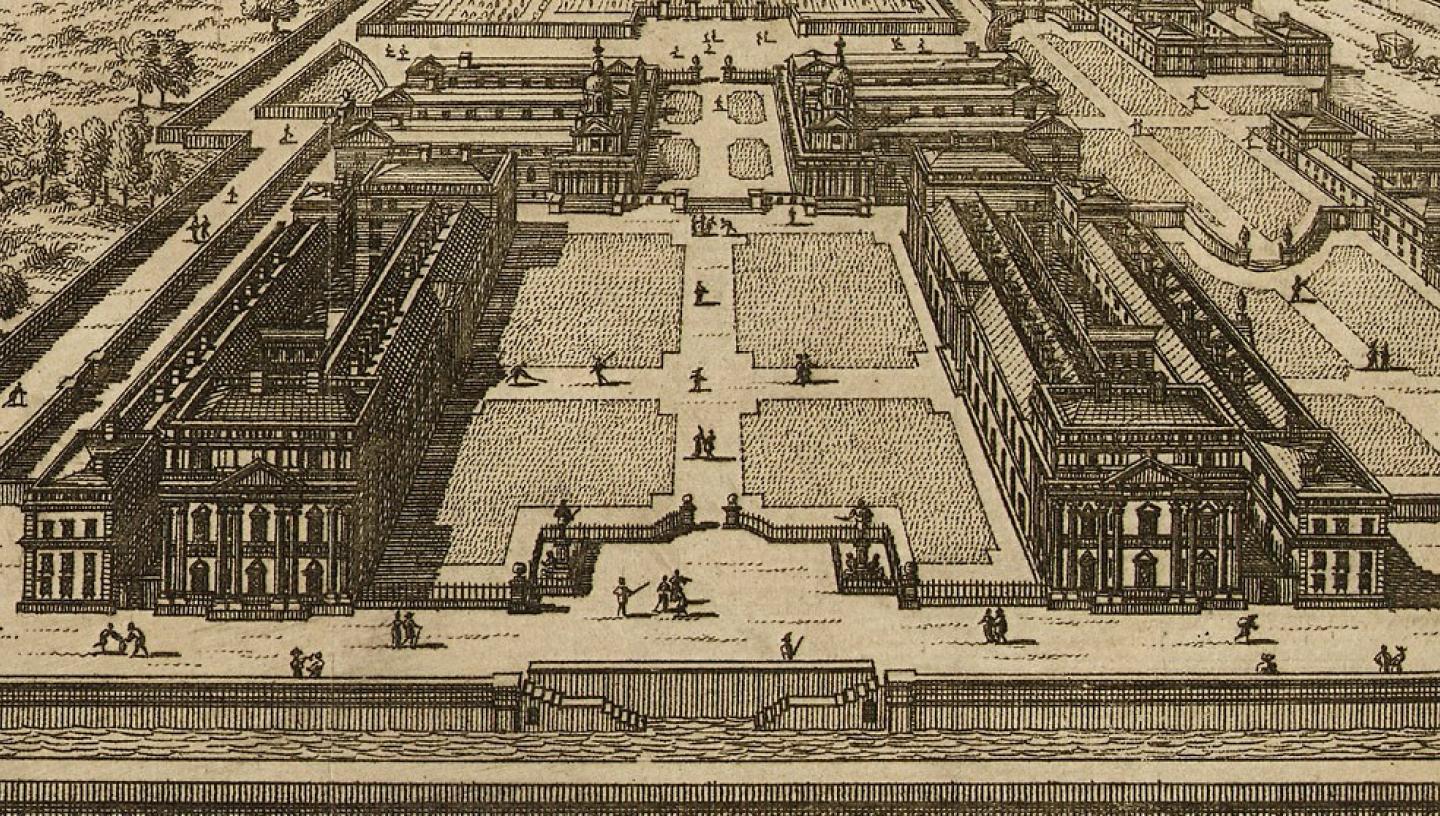

Dr Alexander Copeland Hutchinson, who was born in Devonshire around 1786, was one such case. He studied medicine at Aberdeen University and was then employed by the Navy. He worked on the Almaan, a hospital ship in the Baltic, and various other ships during his career. He was also surgeon to Woolwich Marine Infirmary in 1808, was at Deal Hospital from 1808 to 1815 and then at HM Dockyard in Sheerness from 1824 until 1827.

By this point, Dr Hutchinson had been seeing another surgeon for heart complications and together they felt that he needed a quieter environment to rest his body and mind as he no longer trusted his own judgement. Although Dr Hutchinson was not suffering from a mental health condition, he recognised that working in such an environment while suffering from a heart condition was affecting his mental wellbeing.

Once he retired from the Navy, however, he returned to the medical profession in the 1830s, becoming consulting surgeon at the Royal Metropolitan Infirmary of Children’s Illnesses, which would later evolve into Great Ormand Street Hospital. He died 3 January 1840 at home in London.

Those who suffered from mental and physical health problems were sent to hospitals to recover and some, once discharged from the hospitals, would re-join the Navy. Although Greenwich Hospital was originally set up for retired sailors, it saw its share of residents who suffered from mental health conditions. The archives show that poor mental health affected those at every level. This included Edward Hawke Locker, who in 1819 became secretary of Greenwich Hospital and Civil Commissioner in 1829. Locker continued in his role until his retirement in 1844 due to what was referred to as ‘mental failure’. Today, it would be recognised as Alzheimer’s disease.

A letter to the secretary of the Admiralty, John Croker, from Locker's wife, Eleanor, reveals the reason that Locker had asked to retire. Eleanor explains that her husband had been suffering from forgetfulness for some time and that she had taken him on holiday to see how he would cope in a different environment. Unfortunately, during a walk by himself he seems to have forgotten where he was and was found by a policeman the next day after sleeping in a field overnight and falling into a bog.

Eleanor expresses her distress over the situation and explains to Croker that she would be glad once her husband had retired from work so that she could devote her time to looking after him, rather than helping him fulfil his role at Greenwich Hospital. From the tone of the letter, it can be ascertained that Eleanor had been overseeing Locker's work for some time.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw growing awareness of mental health conditions. The Navy Board seemed used to dealing with those who suffered from different health conditions, although its attitude appeared to remain focused on the administration it generated, the discharge of the sufferer and the hiring of a replacement. It is clear, however, that no one really understood how to treat these health conditions, other than to move them to a ‘more peaceful environment'.