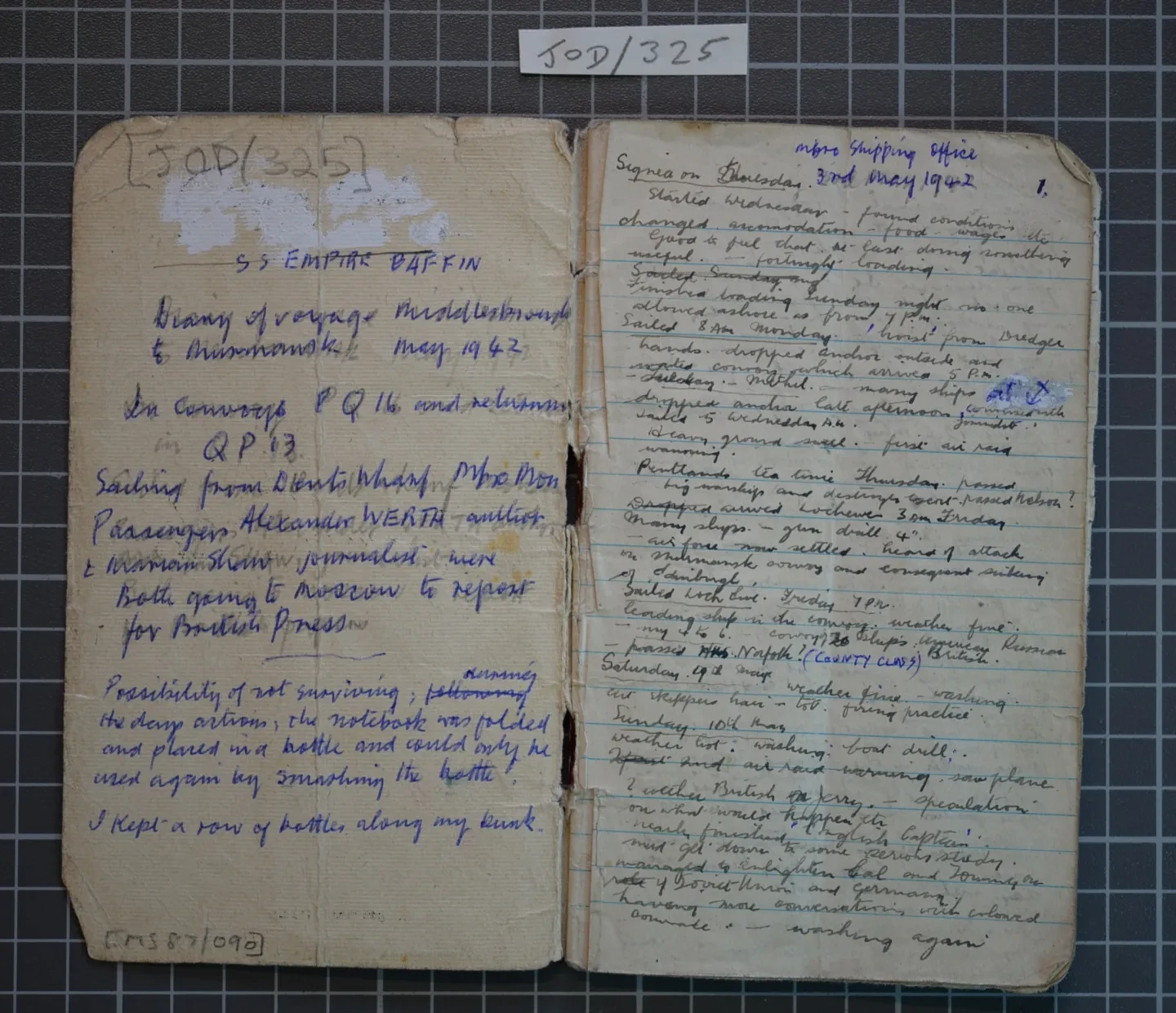

This month we investigate a small notebook from the Journal and Diary collection (RMG reference: JOD/325), kept by Thomas Edward Chilvers from the time he was serving in the Merchant Navy onboard the ship Empire Baffin. The Journal and Diary collection offers a fascinating insight into life at sea in the Royal and Merchant Navy, the fields of exploration and leisure activities in the words of those who contributed to laying the foundations of Britain’s maritime heritage.

Chilvers, born 1911 in Yorkshire, initially volunteered to fight with the International Brigade during his Royal Navy career. The International Brigade was to assist with the defeat of General Francisco Franco, the leader of the Nationalist forces, during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). By April 1939, General Franco was victorious, with the assistance given to his forces by the German Condor Legion.

Onboard the Arctic convoys

In the Merchant Navy in 1941, Chilvers participated in the Arctic convoys, on board the Empire Baffin, which was assigned to convoy PQ16, arriving at Murmansk on the 30th of May. During the voyage, the Empire Baffin was damaged in an air raid but continued its journey and later left Murmansk in late June, bound for Scotland.

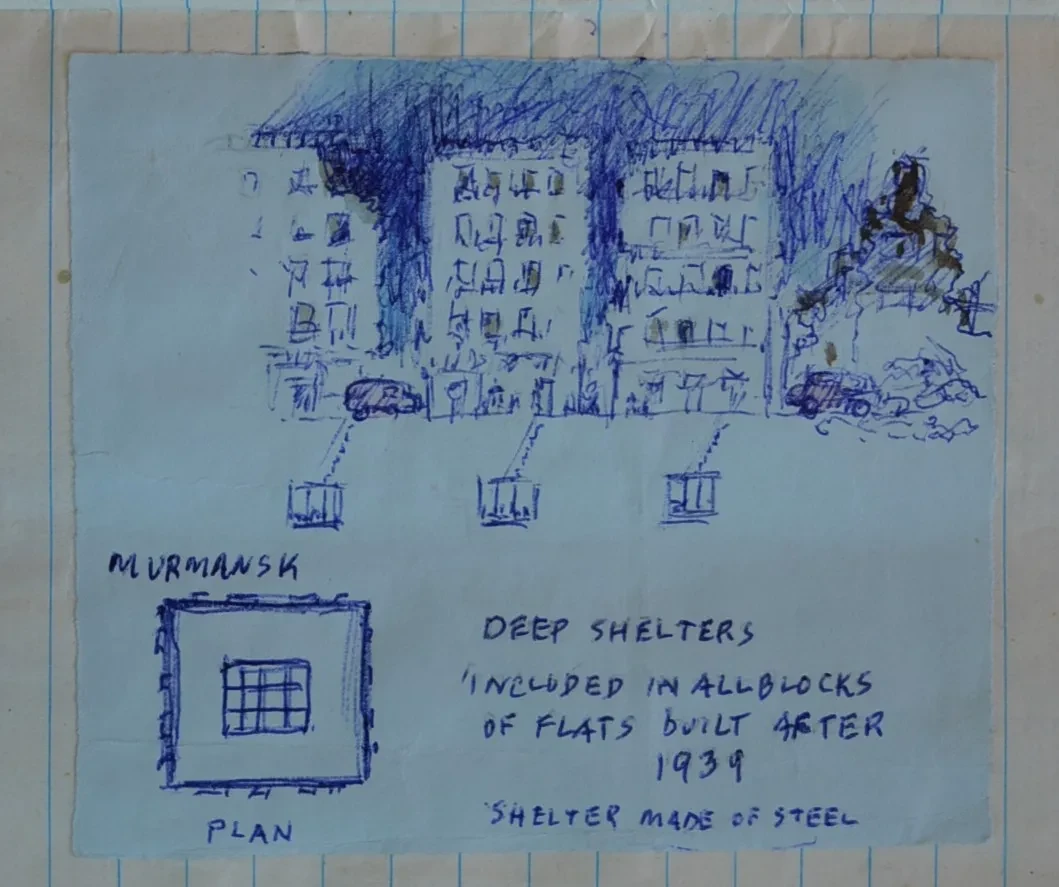

His notebook describes the air attacks on convoy PQ16, routine life on the ship and the experience of taking shelter in Murmansk during air raids. The notebook also includes various sketches, including the loss of the convoy ship Lowther Castle, sunk by torpedo.

Supplying the war

The Arctic convoys were created to supply vital war materials to the Soviet Union. Such supplies were urgently required to ensure that the beleaguered Russians would be able to maintain their fight against the German armed forces, which invaded Russia in June 1941. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the British Government were not enthusiasts of the Communist system; however, Churchill knew to enable a successful conclusion of the war, the Russian contribution would be a vital factor.

The convoys were also a political statement, which the Allies confirmed by undertaking to assist the Soviet Union, at a time when the Allies were not ready to launch a “Second Front” against Germany as demanded by the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin.

The weather was so severe, sailors reported being on deck with a crew member and, after being hit by a wave, they found themselves alone, their colleague swept away, never to be seen again. It was essential the crew did not touch any part of the ship's weather deck (any part of the deck exposed to the elements) with bare hands, as their skin would adhere to the metal.

Parties of men would stand ready to break away large formations of ice which formed on the superstructure of the ship, as the quantity and weight of the ice was so substantial it could destabilise the ship with the threat of a capsize.

The convoys were under constant threat of German air and submarine attack; therefore, if a ship were sunk, no one could survive in the water due to the extreme cold. When a ship was lost, if another stopped to rescue survivors, it would be a static target, especially vulnerable to torpedo attack.

The ill-fated convoy PQ17

The most ill-fated Arctic convoy was code-named PQ17. When PQ17 was approximately six hundred miles distant from its destination, the escort ships were withdrawn on the orders of Admiral Sir Dudley Pound and the convoy ships were ordered to disperse. Admiral Pound incorrectly believed the German battleship Tirpitz was in the vicinity of the convoy.

Despite the losses, the convoys delivered their precious cargo to the Soviet ports of Archangel and Murmansk between 1941 to 1945; approximately four million tons of supplies of arms, vehicles and food were delivered to the Soviet ports. The Russians were grateful for the assistance given by the sailors of the convoys. As a result, after the war, the surviving British sailors were awarded a medal by the Soviet Union.

The convoy veterans did not receive a medal from the British Government until 19 March 2013, titled the Arctic Star, in the form of a bronze star. Next of kin of deceased veterans are also eligible to claim the award.

Find out more...

To enquire about the Arctic Star, please see the Ministry of Defence website - Medals: campaigns, descriptions and eligibility.

Readers may also be interested to visit The Russian Arctic Convoy Museum in Birchburn, Scotland.

Sources used in this post: PQ17 Convoy to Hell: The Survivor’s Story by Paul Lund; The Road to Russia: Arctic Convoys 1942 by Bernard Edwards; Convoys to Russia 1941-1945 by Bob Ruegg and Arnold Hague. These books can be found in the Caird library collection.

To discover more, please visit the Caird Library and Archive.