Delve into the National Maritime Museum collections and find out what life on board a 19th century whaling vessel was really like.

“Death seems close at hand; stares us in the face on all sides,” Charles Edward Smith writes in his diary during an expedition to the Arctic.

Smith was a surgeon on board the Diana, which set sail from Hull in 1866 to embark on a whaling voyage.

The experience was disastrous: the ship became trapped in the ice for six months during the harsh winter. 13 crew members perished.

Life on a whaling vessel during the 19th century was fraught with danger. Death was a constant threat, whether from illness caused by the poor nutrition and unsanitary conditions on board, injury or being trapped on capsized vessels. The crew were often away from their friends and family for months at a time.

This treacherous world is the basis for The North Water, a BBC drama series starring Colin Farrell and Jack O’Connell. The series is based on the novel by Ian McGuire, and follows the calamitous exploits of the crew on The Volunteer, a fictional whaling ship which set sail from Hull in 1859.

From journals to panels, explore items from the National Maritime Museum's collections that give an insight into the whaling industry during this period.

In search of whales

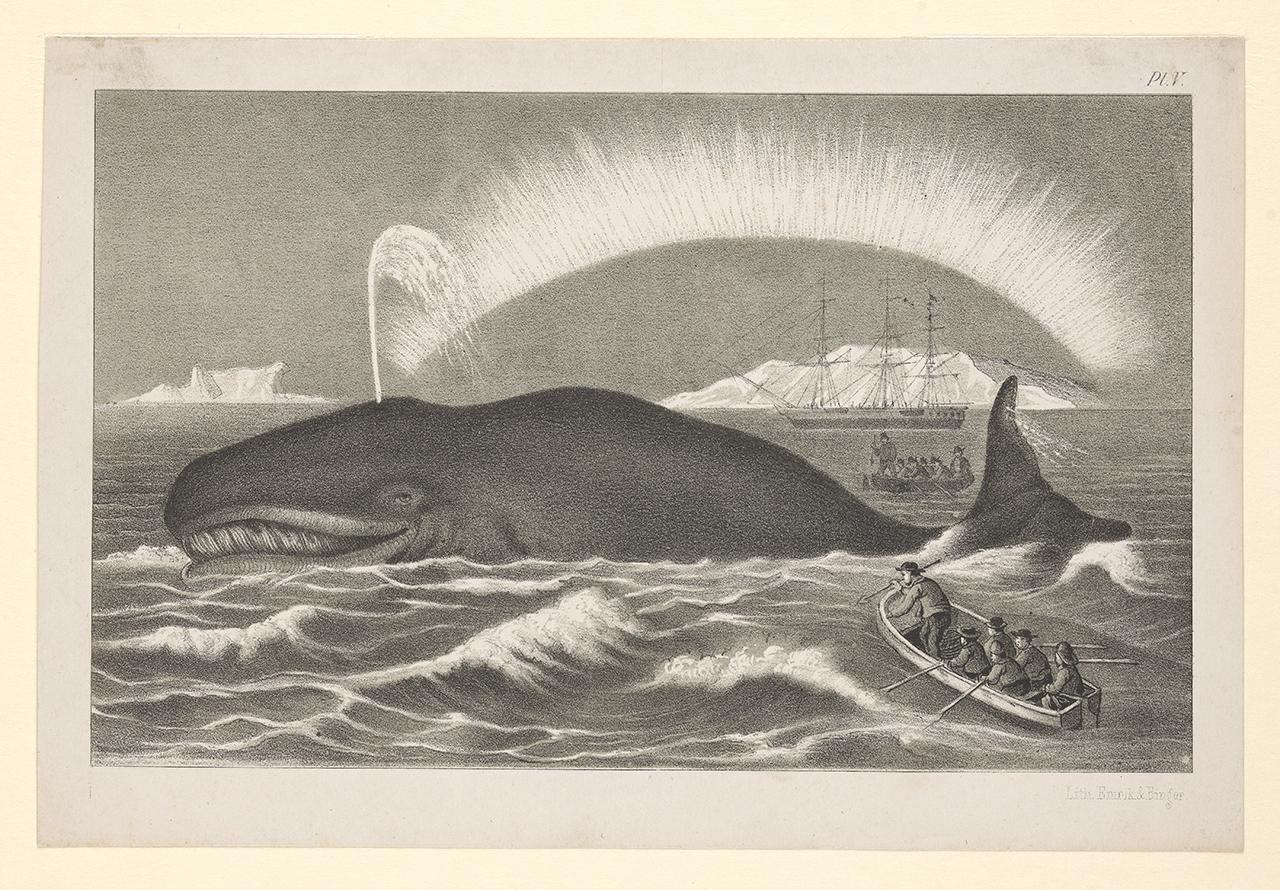

This 19th century print shows a whale hunt in action.

“Whales were hunted primarily for oil,” Maya Wassell Smith, PhD researcher at Royal Museums Greenwich, explains. “Whale oil had many uses, from lighting to lubricants for machinery.”

In the scene, two small boats can be seen approaching the whale. Alexander Trotter, a doctor on board the Enterprise, gives an insight into how whales would have been captured in his 1856 journal To the Greenland whaling.

He explains that upon sighting a whale, two small boats would be lowered from the main ship into the water. The smaller boats each contained six men, “a loaded harpoon gun” and a “long line coiled up in the bottom of the boat attached to that harpoon.”

On reaching the whale, the men would fire their harpoons and lance and tow it back to the main ship. The crew would then prepare the whale for butchering.

“The flesh of the whale would have been boiled down until the fat became oil, and then stored in barrels below deck,” Wassell Smith says.

In the Arctic regions, the baleen from baleen whales – the fringed plates that filter food from the sea – was also used.

“The baleen was used in multiple ways, particularly for fashion items, such as umbrellas and corsets,” according to Wassell Smith.

Whaling records and documents

One of the most important items on a whaling ship was the logbook, which kept a record of vital information relating to the voyage, including its dates, locations visited, weather conditions, details of incidents that occurred, as well as information about when and where whales were captured.

The logbook could also record other details relevant to the industry, including the measurements of the whale and the barrels of oil it yielded.

This logbook from the Caird Library and Archives was kept by Captain Edward Bell on the whaling ship Unity, which sailed from Hull to Greenland between April and August 1818.

By the 19th century, Hull was one of the most significant whaling ports in Britain – and the port of departure for the crew in The North Water.

Between 1815 and 1825, it is estimated that around 2,000 people were employed in the city’s whaling trade. Other whaling centres during this period include Dundee, Aberdeen, London, Liverpool and Peterhead.

Explore the Caird Library

Whaling traditions and customs

Despite the hardships endured at sea, the crew of whaling vessels could still find time for entertainment.

The journal of George William Manby, written during a voyage to the Arctic in 1821, reveals the unique customs that took place on board.

In an early entry, he gives a detailed description of the celebrations that took place on May Day: “No sooner had eight bells struck to hail the arrival of the festive day, than the most grotesque group of figures imaginable advanced slowly towards a garland, composed of hoops, decorated with ribands, that was already suspended from the mizen stay, by the last married man in the ship.”

Wassell Smith explains that the event was an important rite of passage for new sailors.

“The May Day celebrations were an initiation ceremony for younger sailors who had never been on an Arctic whaling voyage before,” she says. “They were also a calendar event, and had their origins in the May Day ceremonies that took place on land.”

As part of the initiation ceremony, Manby describes how a sailor dressed as Neptune – wearing a “loosed cloak with a border of old blanket, tufted with rope-yarn to represent ermine” – chose certain seafarers to be his ‘prisoners’. These prisoners were covered in a lather mixed with “soot and grease” and shaved.

But, Wassell Smith explains, the ceremony wasn’t enjoyed by everyone.

“The ceremony could be quite violent, and even traumatic for some young crew members,” she says, “if crew members had a grudge against someone, the ceremony was the place to work it out.”

In his account of the day’s events, Manby explains that the festivities ended with a procession, which was filled with “the melodious tones of frying-pans, kettles and clashing pot-lids.”

Personal belongings at sea

Dating from the early 19th century, this object is known as a seam rubber. It would have been used to produce a sharp fold in sail fabric before sewing.

The tool is one of many items from this period that were made from whalebone. It features an elaborate rope twist pattern on the handle. Wassell Smith explains that the initials ‘JK’ and ‘WB’ on the head of the tool could provide an insight into its acquisition.

“At sea, things changed hands in different ways, from men giving presents to each other, buying things off each other, or winning or losing things in gambling and betting,” she says. “The initials on the seam rubber record this movement.”

Another way that items changed hands at sea was through sales at the mast – a practice referenced in the first episode of The North Water.

“When someone died at sea, their belongings would go up for auction to the crew a few days later,” Wassell Smith says. "While we don't know for certain that the seam rubber was sold at one of these auctions, the fact it has two different sets of carved initials suggest it might have been." She adds that the intricate carving of the tool offers an insight into the value seafarers placed in craftsmanship and personal belongings.

Whalebone and 19th century sailor crafts

Made from a sperm whale’s lower jaw, this panel shows a whaling vessel at sea. Three small boats and a whale’s head can be seen in the foreground, while in the background, a group of whales swim in the distance.

Like the seam rubber, Wassell Smith explains that the panel is an example of ‘scrimshaw’ – a genre of crafted objects made mostly by men working on whaling ships. The panel is likely to have been decorative, and the two holes drilled into it suggest that it would have been hung like a picture or painting.

“There were multiple reasons why whalers were making these sorts of objects,” Wassell Smith explains. “It was a way of occupying their time usefully while they were away, and the items could be given as gifts. It was also another way of making money, and there’s documentary evidence of men making things and selling or trading them with one another.”

For Wassell Smith, one of the most intriguing details in the panel is the rendering of the coastline and mountains in the background.

“Based on the seascape depicted in this artwork, there’s a possibility that this item might be related to the southern whale fishery – which was centred around the Pacific region – rather than the Arctic fishery,” she says.

Hope for whales

With the advent of the 20th century, demand for whale products began to decline, as new lighting and heating technologies emerged. Yet whale populations continued to plummet.

Early international agreements laid the foundation for the formation of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) in 1948.

In 1982 the International Whaling Commission (IWC) called for a 'moratorium' on commercial whaling, and this came into force in 1986. However, this has not led to an outright ban. The IWC tracks the numbers of whales caught and publishes the data on individual nations here.

Visit the Polar Worlds gallery

Main image courtesy of the BBC