As long as there have been military campaigns there has been espionage. Here we look at some examples of written intelligence from spies which can be found in the Caird Library and Archive

The beginning of espionage

Britain, in the last 500 years, has faced threats such as the invasion of Philip II’s Spanish Armada of 1588, Napoleon, and the First and Second World Wars. During each of these periods spies were used to both gather intelligence or lay false intelligence.

But espionage is not new to the last 500 years. The Romans also had their own legacy of spies that forced Emperor Titus to reform the spy network when their greed led to panic and terror.

One notorious Roman spy was Regulus, during the time of Emperor Nero. Regulus had become famous for accusing innocent people of treason.

It is also believed that the Aztecs used Pochtecas (long-distance merchants) to gather intelligence across the Aztec empire and Quimitchin to infiltrate other tribes by wearing the local costume and speaking the local language.

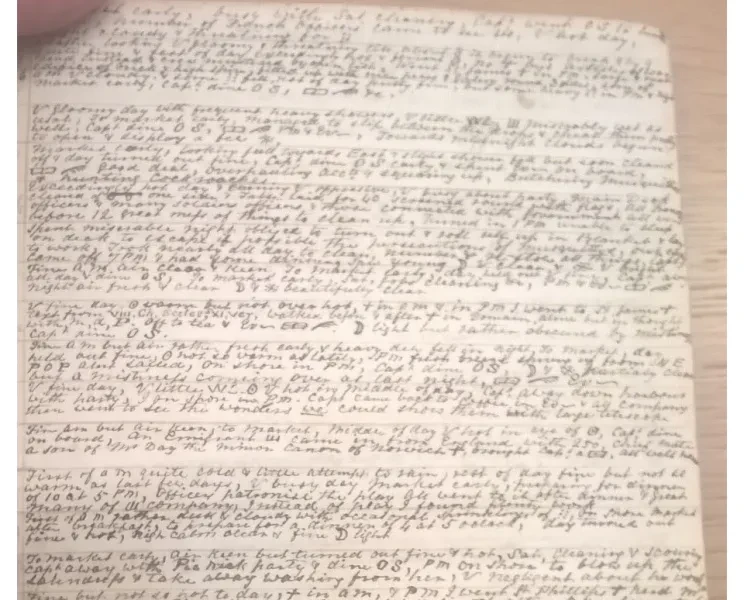

The Caird Library and Archive holds a spy book written by William Lyttlestone, a diplomat in Spain. The first lines read:

“To the worshipful and singular good friend master Doctor Dale esquire master of the requests onto the Queen most excellent majesty. Whilst I abode, right worshipful, in the court of Spain, time permitted me to view and search for the some parts of the secrets and state of the Realm of Spain and parts of the Realm of Portugal as by sight of the muster books …”

Two hundred years after William wrote his intelligence book, the Home Office was formed by renaming the existing Southern Department.

A man by the name of Evan Nepean would go from joining the Royal Navy to becoming Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the newly formed Home Office in 1782, in just nine years.

Evan Nepean

Cornwall-born, Evan Nepean was the second son of Nicholas Nepean, an innkeeper, and his second wife, Margaret Jones. His chosen career moved quickly. Upon entering the Royal Navy on 28 December 1773, he served in the Boyne as a clerk to Captain Hartwell. He was promoted to purser in 1775, and during the American Revolutionary War, he served as secretary to Admiral Molyneux Shuldham. From 1780–1782, he was Purser in the Foudroyant for Captain John Jervis (later Lord St Vincent).

On 3 March 1782, aged only 29, Evan Nepean was appointed Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department and became responsible for naval and political intelligence. His career didn’t stop there. He served until 1791, when he became Under-Secretary of State for War in 1794, Secretary to the Board of Admiralty 1795–1804, Chief Secretary for Ireland 1804–1805, Commissioner of the Admiralty, and then Governor of Bombay 1812–1819.

Evan set up the system of surveillance in London in 1782. By 1792 it was still being conducted by William Clarke, 12 assistants and Evan Nepean signing off the receipts.

Consisting of less than two dozen people, Nepean decided to recruit more people and send out informers to coffee houses and taverns. By this point it was agreed that the French Republicans had infiltrated London society.

Agents

The Secret Service used a number of agents from all walks of life and countries. Here are a select few from our archives.

Philippe d'Auvergne

A naval officer from Jersey. Beginning under Lord Howe, he served in Russian, Arctic and American waters. When he was the 1st Lieutenant in the Arethusa, he was wrecked off the coast of Ushant and became a prisoner of war in France. He later went on to serve in the Lark and the Rattlesnake, and by 1787, he served in the Narcissus to watch the French Channel Ports.

Richard Cadman Etches

Fur trader turned agent Richard Cadman Etches was originally recruited by Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, in 1783. In 1790, with a detailed knowledge of North Sea and Baltic ports, he switched allegiance and gave information to the British authorities. For at least six years, Etches was considered a threat and on probation until he proved himself. In 1798, he was instrumental in the rescue of Sir Sidney Smith from the Temple prison in Paris.

Jacques-Antoine Du Roveray

Born in Geneva, Du Roveray was a lawyer who practised in a notary's office and became one of the heads of the Representatives of the city of Geneva. He accepted the help of England to provoke the independence of Geneva. In 1779, he was appointed the public prosecutor, but a request from France saw him dismissed and exiled by 1782.

In England he received a warm welcome and set up the Geneva colony in Ireland. In 1792 he was in Paris working with the Secret Service and in September 1793 he was in Switzerland sending regular Intelligence Reports.

George Parker

An ex-soldier who spoke French and Portuguese. Evan Nepean had often used Mr Parker’s surveillance skills to watch suspicious characters. These included Mrs White, an American artist who was passing on intelligence in letters addressed to Philadelphia; the Duke of Orleans; Colonel Francisco Miranda and a man by the name of O’Callaghan.

Unfortunately, after being associated with Mr Thompson, an English spy who couldn’t hold his alcohol, he fell out of favour with Nepean. He ended up in Fleet Prison, where he met Thomas Augustus Smith Murray, a man claiming to be the illegitimate child of Prince Frederick.

Nepean often received information from various people in all walks of life, many of whom were just hoping to be of some use to him. Here we have a payment to Mr Wolstoncroft for information of a plan formed by Mr Fulton at Brest for the destruction of the British Fleet. This was paid by the Earl of St Vincent on behalf of the Secret Service.

Ciphers and codes

Many of us watch action movies about spies and are used to hearing the words: ‘Our forces have intercepted this coded message’.

It seems strange to think that the military were not using codes in the early years of the Secret Service. At this stage most encryption and enciphering was done by diplomats within the Home and Foreign Offices. The military naval forces and agents were not entrusted with ciphers and in general just had to hope that their letters were not intercepted.

Here we have a letter from Francis Drake (a British diplomat), holding positions at Genoa, stating it is in a terrible crisis. Part of the letter uses ciphers to hide the message. Next to it is an enclosing note deciphering the words in code.

By 1815, after the French Revolution and the American Wars, the Secret Service was well on its way to becoming the modern service we see today.

The Crimean War of 1854 saw the establishment of the Topographical & Statistic Department, further developing the intelligence organization. 1882 saw the Naval Intelligence Division develop as the independent intelligence arm of the British Admiralty.

By 1909 the Secret Service Bureau was a joint initiative of the Admiralty and the War Office to control secret intelligence operations in the UK and overseas, specializing in foreign intelligence. The section experienced dramatic growth during World War I and officially adopted its current name of Secret Intelligence Service around 1920.