In this blog we uncover some of the stories which our archives can tell us of the dangers of working in the British Empire in the service of the East India Company

By Victoria Syrett, Archive Assistant

The Caird Library and Archive works with lots of other departments across the Royal Museums Greenwich sites, from conservation (endeavouring to protect the documents we work with) to exhibitions (for designing display cases).

One department we work with on a weekly basis is the education team, providing a manuscript session for a series of lessons offered to schools.

These sessions include the Spanish Armada invasion of 1588, Transatlantic Slavery and Abolition, and the British Empire - how trade became an Empire.

The British Empire is our most recent addition and during the manuscript session we analyse the dangers the Honourable East India Company (HEIC) had to overcome to develop its trade - let alone become the basis of an Empire. Some of these dangers are listed below.

Shipwreck

Before the mid-18th century and the development of accurate instruments, successful navigation relied on the skills and knowledge of individuals.

Navigation at sea was always dangerous. Sailors might not see land for weeks at a time and shipwreck was a constant danger. About five per cent of the Company's ships were wrecked or lost at sea.

Frosty receptions

Even if a crew member managed to survive a shipwreck and get to shore it was often very difficult to return to England from Asia. This was especially true in the earlier periods when there were fewer ships.

Company servants could also be imprisoned by local rulers or captured by pirates. On other occasions, Company trading posts and settlements were attacked.

Illness

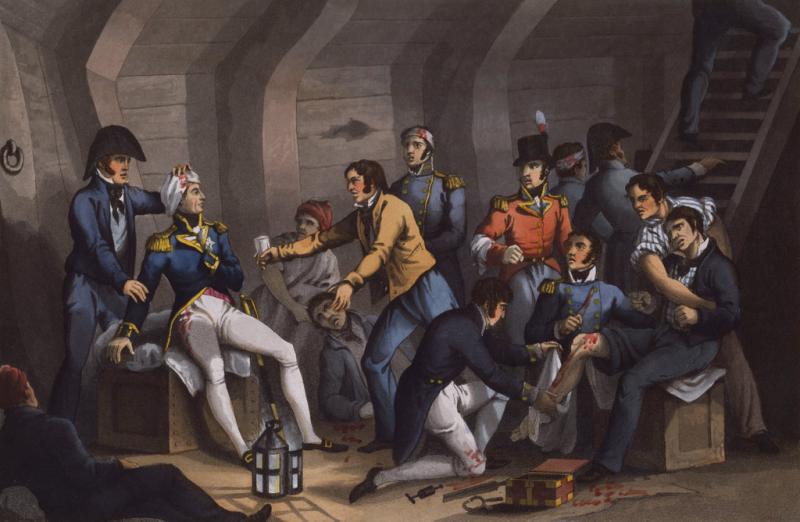

Illness was common on board ship during the early voyages. Scurvy and the ‘flux’ (dysentery) claimed many victims, as did the unsanitary conditions. More than 100 out of 480 men had died by the time Sir James Lancaster's first fleet rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1601.

Even on shore, a sailor or merchant was not safe. The ports and trading posts that the Company's officials visited harboured many unknown diseases to which they did not have any resistance.

It was thought to take five years to acclimatise, but most people were lucky to last two monsoons. In some years, a third of Company staff died of cholera, typhoid, and malaria.

Rival powers

Competition between European trading companies was always fierce. Outbreaks of violence between the Company's servants and its Dutch and Portuguese rivals were common.

One of the most notorious episodes was the execution by the Dutch of ten Company merchants on the spice island of Ambon in 1623.

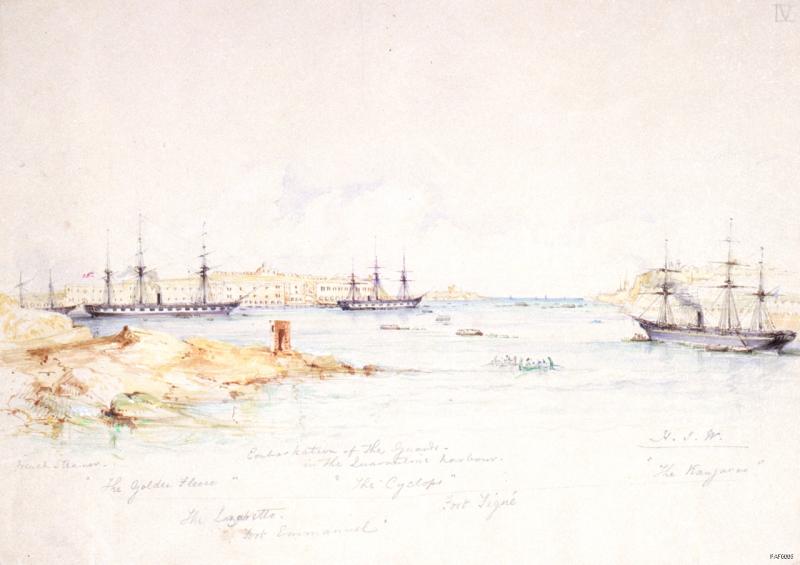

In the 18th century, the Company was at war with the French in a struggle for commercial supremacy on the Indian subcontinent. During the fighting, the Company's trade became a target. Fleets of East Indiamen sailing along the trade routes were vulnerable to attack from French warships.

Stories from the archives

Dangers at sea: pirates and weather

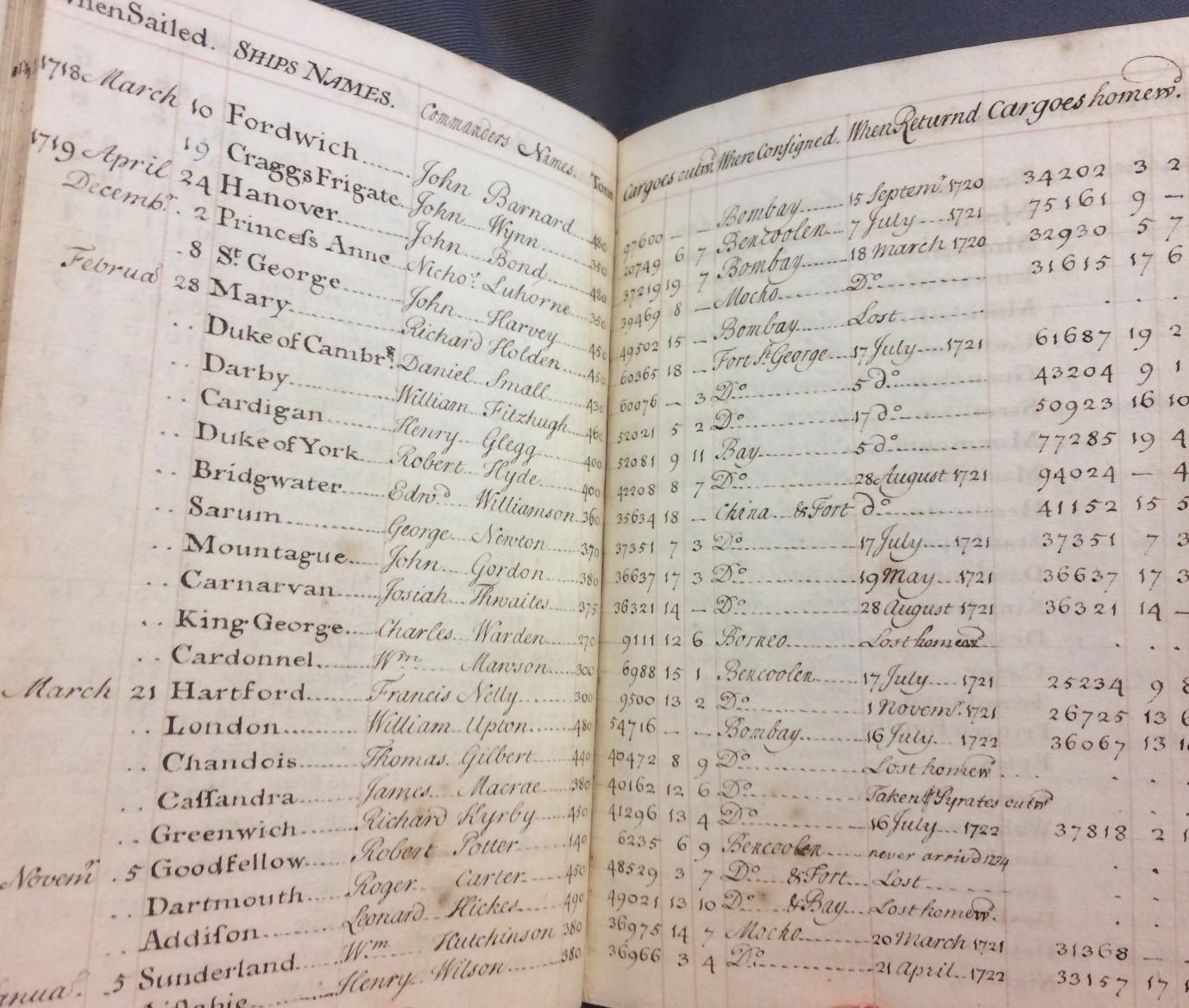

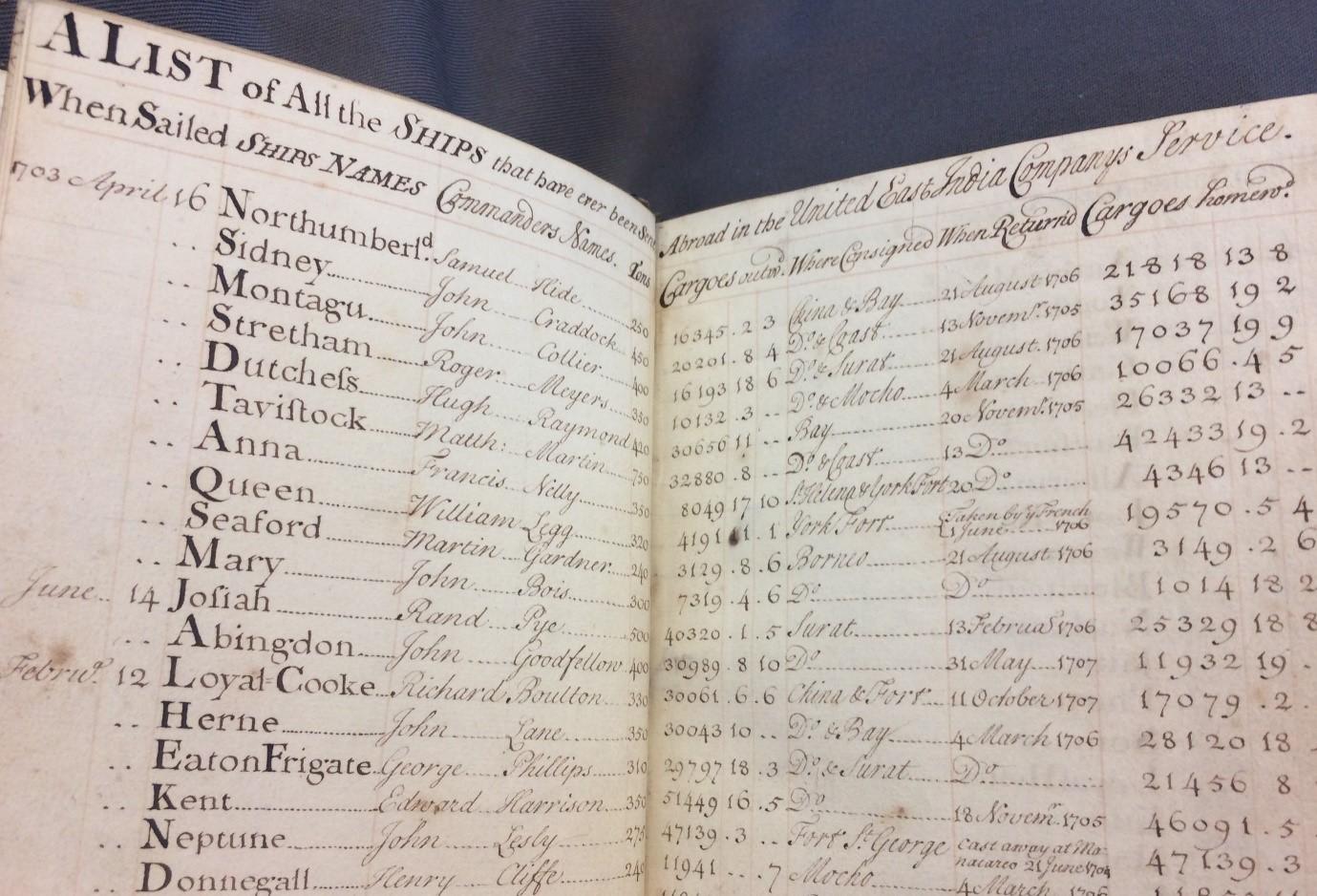

This manuscript lists the ships, when they sailed, who the commander was and when they returned.

You can see that the Cassandra left on 21 March 1719 and was taken by the Irish-born pirate Edward England near the Comoros archipelago to the north of Madagascar.

During the fight with the pirates 13 crew members were killed and 24 wounded. Among them was Commander James Macrae, who had been struck by a musket ball on the head. Some of the crew escaped in the long boat and some by swimming.

They managed to reach the shore, leaving on board three wounded men who could not be moved, and who were butchered by the pirates.

The Neptune, 275 tons, 55 crew, 20 guns, left English shores on 12 February 1703 and sailed to Fort St George commanded by John Lesley - but is recorded as ‘Cast away at Mancaree 21 June 1704’.

The local people at Cape Comorin had carried off 30 chests of treasure washed up from the wreck.

The Queen, 320 tons, 64 crew and 26 guns, set sail on 16 April 1703 with Commander William Legg, but was captured by the French at Saint Helena on 1 June 1706.

It was on the homeward leg of its second voyage; George Cornwall, the captain, was killed in the action.

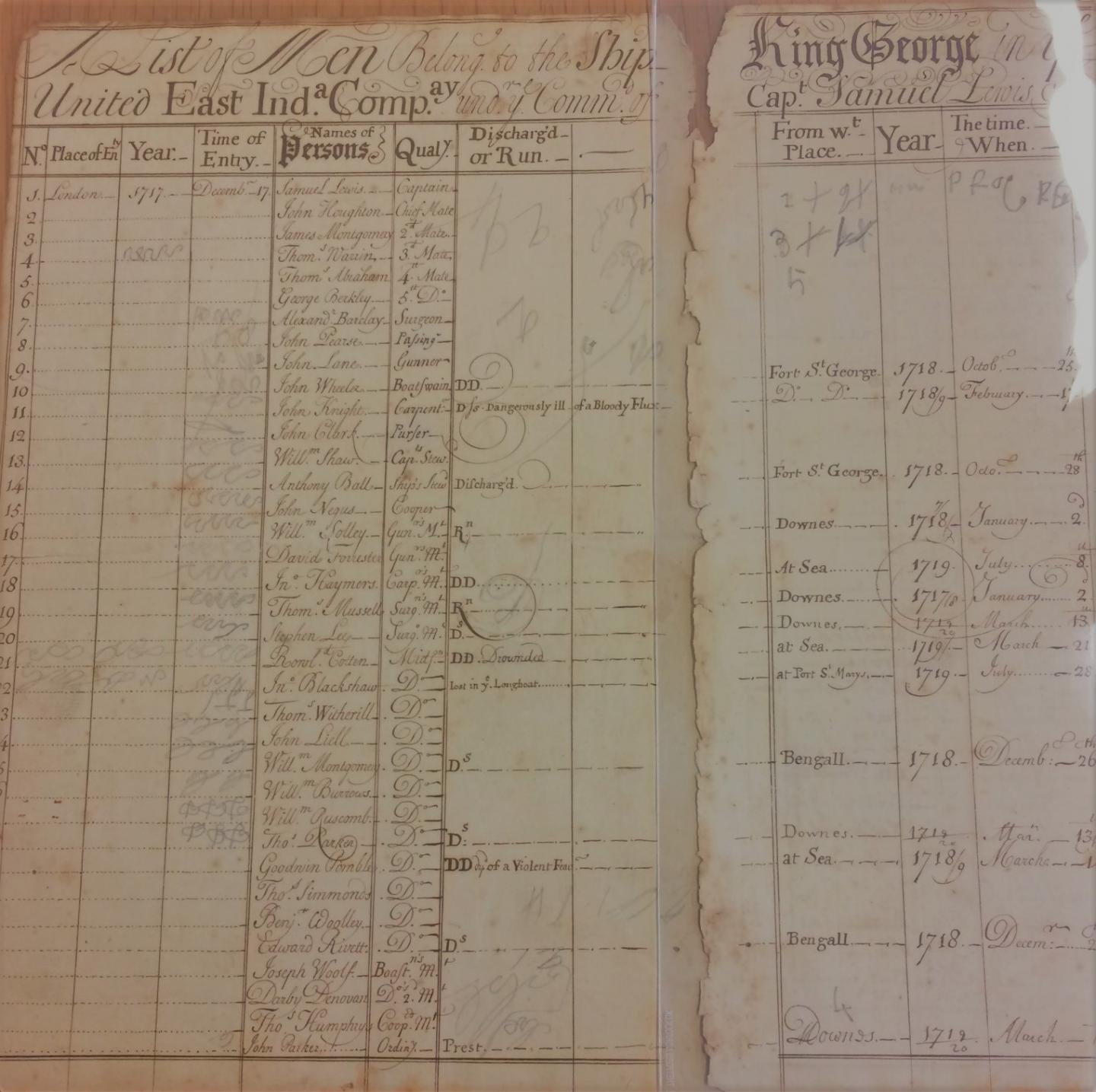

This logbook covers the years 1717-1718 and contains a crew list. Some of the crew would have been on a long boat.

Note this is a different King George from that which was lost at sea in AMS/29 – see image above.

The crew list also shows the consequences of a typical voyage, including those that died at sea due to violent fevers and those that are discharged due to the flux.

The other interesting point to note about these pages is that it shows the history of the log itself. We can see when these pages were removed or fell out of their binding and the fact that a child at some point has drawn over it.

The dangers at sea from a simple accident

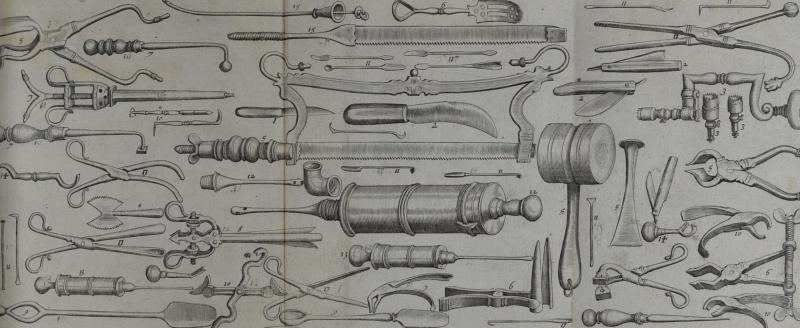

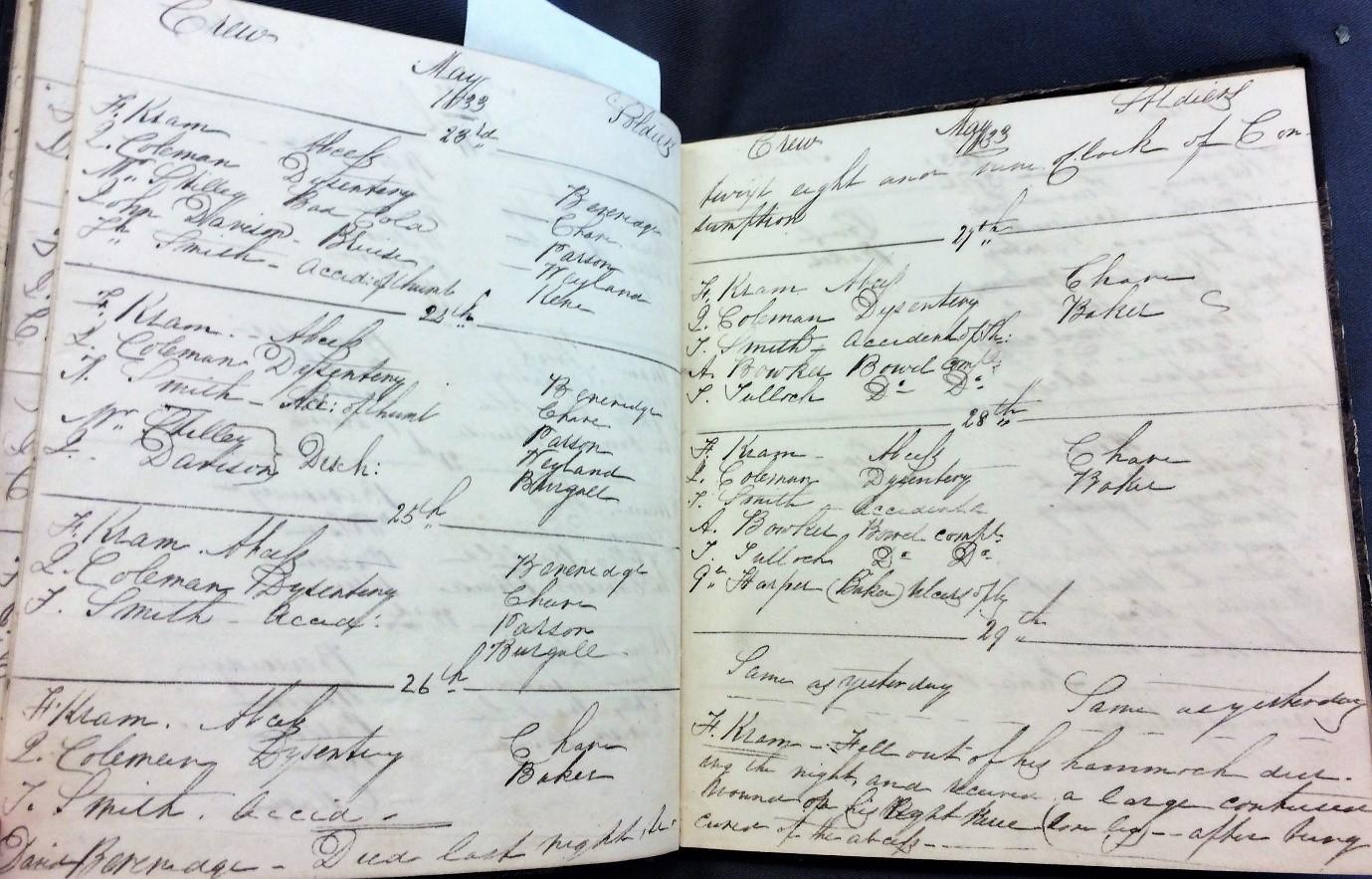

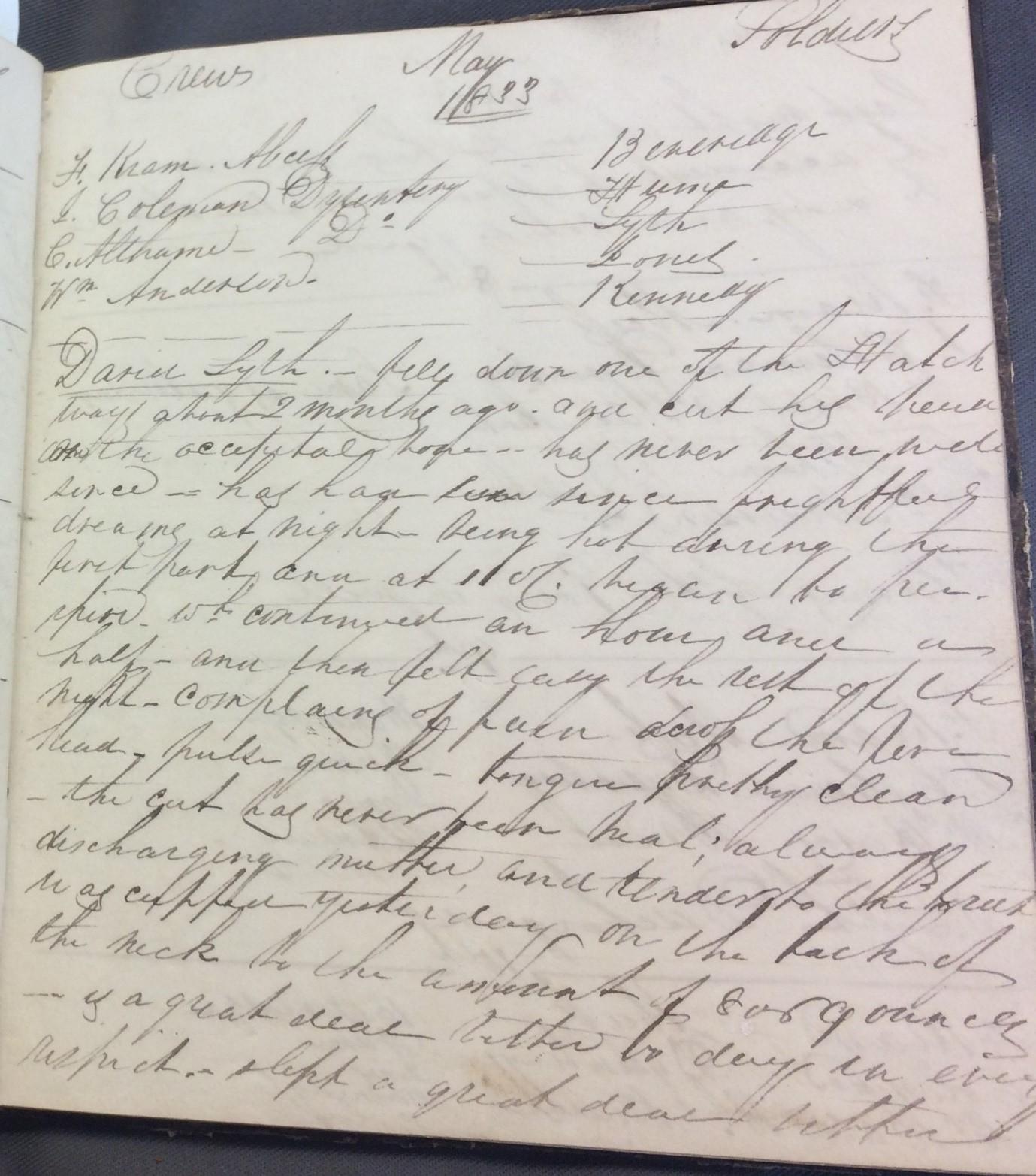

This medical journal covers the voyage of the HEIC ship Warren Hastings and is written by Alexander Coventry, Assistant Surgeon. It covers injuries of both crew and soldiers such as sprains, rashes, infected knees, ulcers, accidents, and a scarlet lump on the forehead causing pain behind the eyes and forehead.

Alexander listed the details for the crew and soldiers on two separate lists. The journal shows that by 1833 the East India Company had its own soldiers.

On 26 May 1833 the journal records that David Brown aged 28 died around 1am the previous night of ‘Consumption’ (pulmonary tuberculosis).

The journal also shows that F. Kram had been seeing the doctor for a few days for his abscess until the 29 May when he fell out of his hammock during the night and received a large contusion wound on his right leg.

This entry has a list at the top including Kram for his abscess and Coleman for dysentery, but under the ‘Soldiers’ heading it lists Lyth with a full description underneath.

‘David Lyth – fell down one of the hatchways about two months ago and cut his head on the occipital lobe – has never been well since – has had ever since frightening dreams at night being hot during the first part and at 11 o’clock began to perspire which continued an hour and a half and then felt easy the rest of the night. Complaining of pain across the forehead – pulse quick – tongue pretty clean – the cut has never been healed always discharging matter and tender to the touch … cupped yesterday on the back of the neck to the amount of 8 to 9 ounces … slept a good better.’

Dangers from the crew: punishment

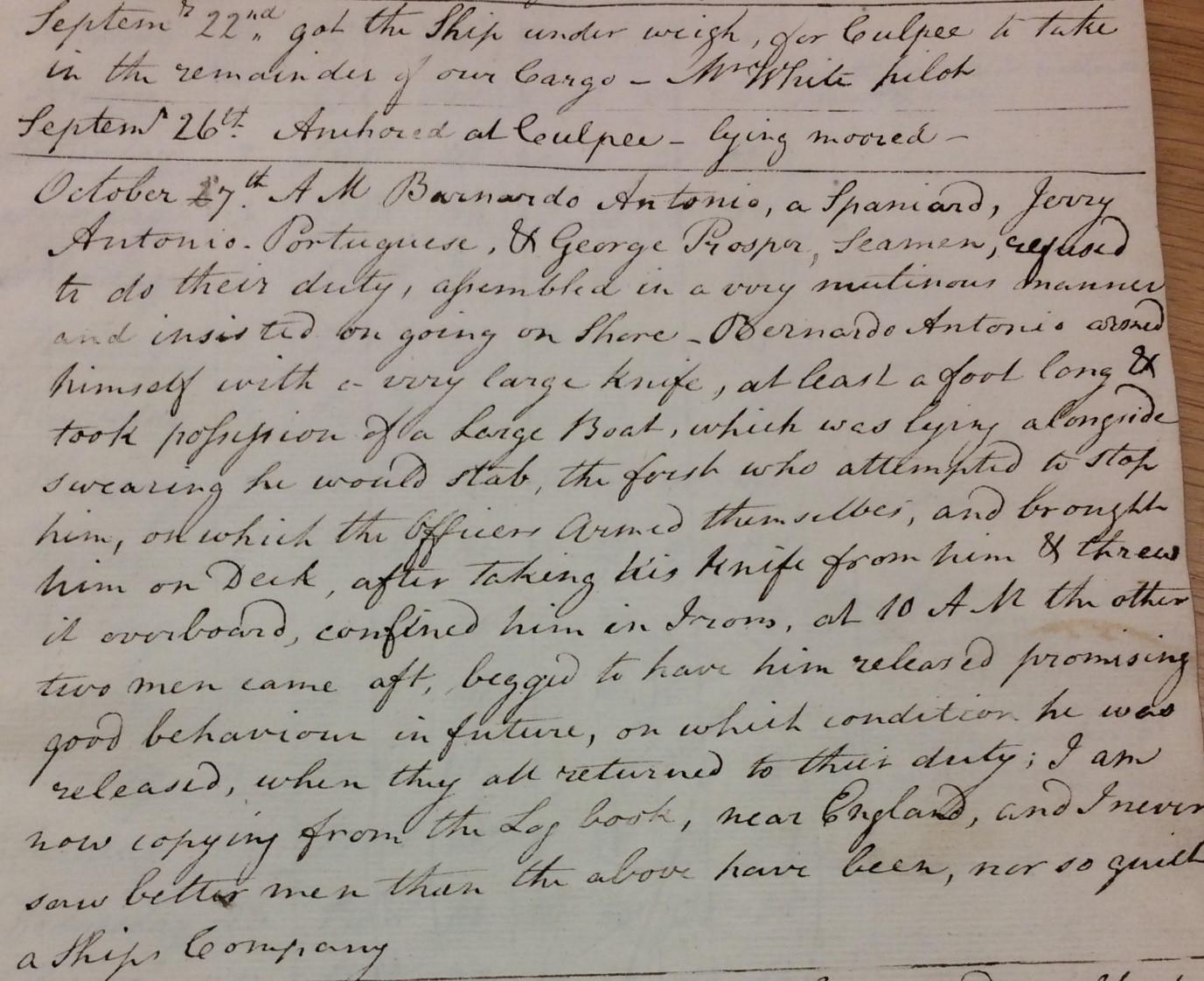

The journal covers a voyage from England to Madras, Calcutta and Bengal and the return journey.

It begins with lecture notes on medicine. The other side of the volume starts with two pages of medical notes relating to the treatment of two privates in the Light Dragoons.

There is then a list of the ship's company followed by a log of the voyage. The log mentions disciplinary actions taken after a minor mutiny on 7 October 1799 where Bernardo Antonio, a Spaniard; Jerry Antonio, Portuguese; and George Prosper refused to do their duty and wanted off the ship.

Bernardo, who was threatening people with a large knife, was eventually put in irons. He was released after the other two begged on his behalf and they never stepped out of line for the rest of the ship’s voyage.

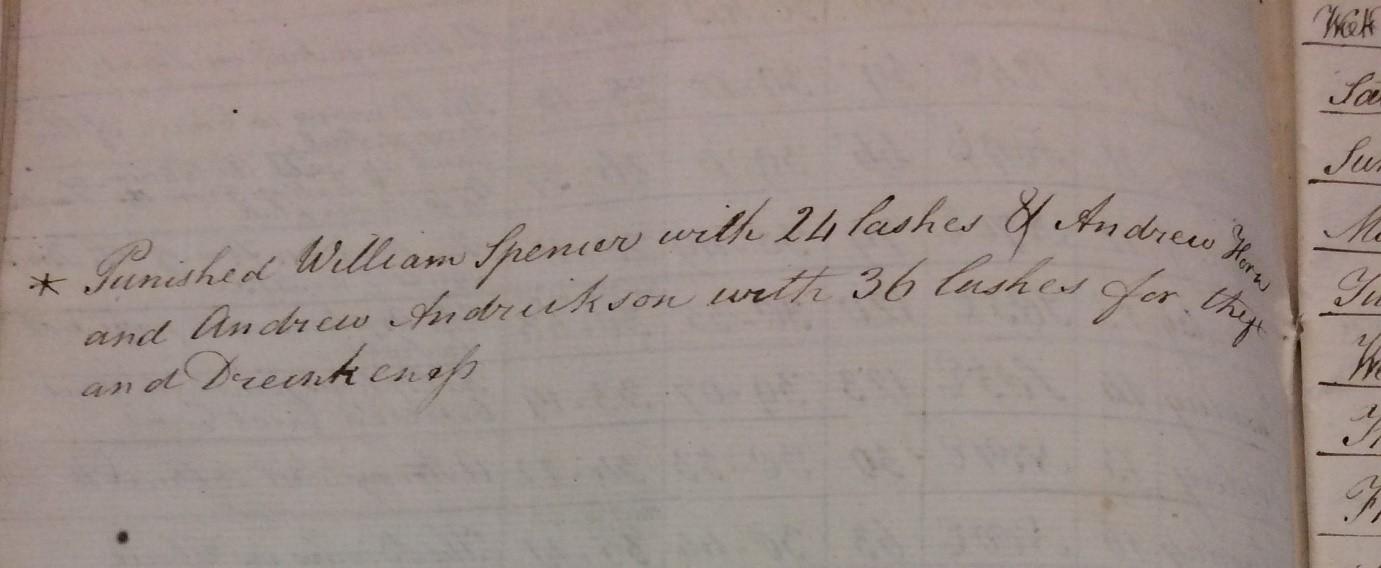

He was let off lightly compared to William Spencer who suffered 24 lashes and Andrew Horn and Andrew Andrickson with 36 lashes for theft and drunkenness.