The Caird Library and Archive’s new display case gives a brief insight into the world of spies through their own words

Spies and spying date back thousands of years, with espionage recorded in Ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire. Over the last 500 years, spies have played an important role gathering intelligence and spreading disinformation as Britain has faced invasion threats from the Spanish Armada, Napoleon Bonaparte and during the First and Second World Wars.

The secret gathering of naval and political intelligence was of vital importance in staying one step ahead of the enemy during the late eighteenth century, a time when conflict was raging in Europe and America. Responsibility for running this intelligence service on behalf of the British fell to Evan Nepean from 1782, when he was appointed Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department.

Evan Nepean

Cornish born, Evan Nepean was the second son of Nicholas Nepean, an innkeeper, and his second wife, Margaret Jones. On entering the Royal Navy on 28 December 1773, he served in the Boyne as a clerk to Captain Hartwell. He was promoted to purser in 1775 and, during the American Revolutionary War, 1775–83 he served as secretary to Admiral Molyneux Shuldham. From 1780–82, he was Purser in the Foudroyant for Captain John Jervis (later Lord St Vincent).

On 3 March 1782, aged only 29, Nepean was appointed Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department and became responsible for naval and political intelligence. During this time, he kept detailed records of payments to his spies. These included Mr Lempriere who was paid £163 ‘for particular services’ and Richard Cadman Etches (see below) ‘for particular service performed by him’.

Nepean set up the system of surveillance in London in 1782. By 1792, it was still being conducted by William Clarke, 12 assistants and Nepean signing off the receipts. With a department consisting of fewer than two dozen people, Nepean decided to recruit more people and send out informers to coffee houses and taverns. By this point it was agreed that the French Republicans had infiltrated London society.

Richard Cadman Etches

Richard Cadman Etches, born in Warwickshire in 1753, was a fur trader turned agent. He was originally recruited by Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, in 1783. Nepean, believing that Etches was dangerous, had kept a close eye on him when he was in London in the 1780s. In 1790, with a detailed knowledge of North Sea and Baltic ports, Etches switched allegiance and gave information to the British authorities. For at least six years he was considered a threat and on probation until he proved himself.

By 1796 he wrote to Earl Spencer, offering to spy for him as he was a certified purchaser of prize vessels and was therefore permitted to visit all French Ports. He would gather marine intelligence and would secretly pass the information on to the blockade fleet that searched his vessel on his way home to Britain. In 1798, he was instrumental in the rescue of Sir Sidney Smith from the Temple prison in Paris.

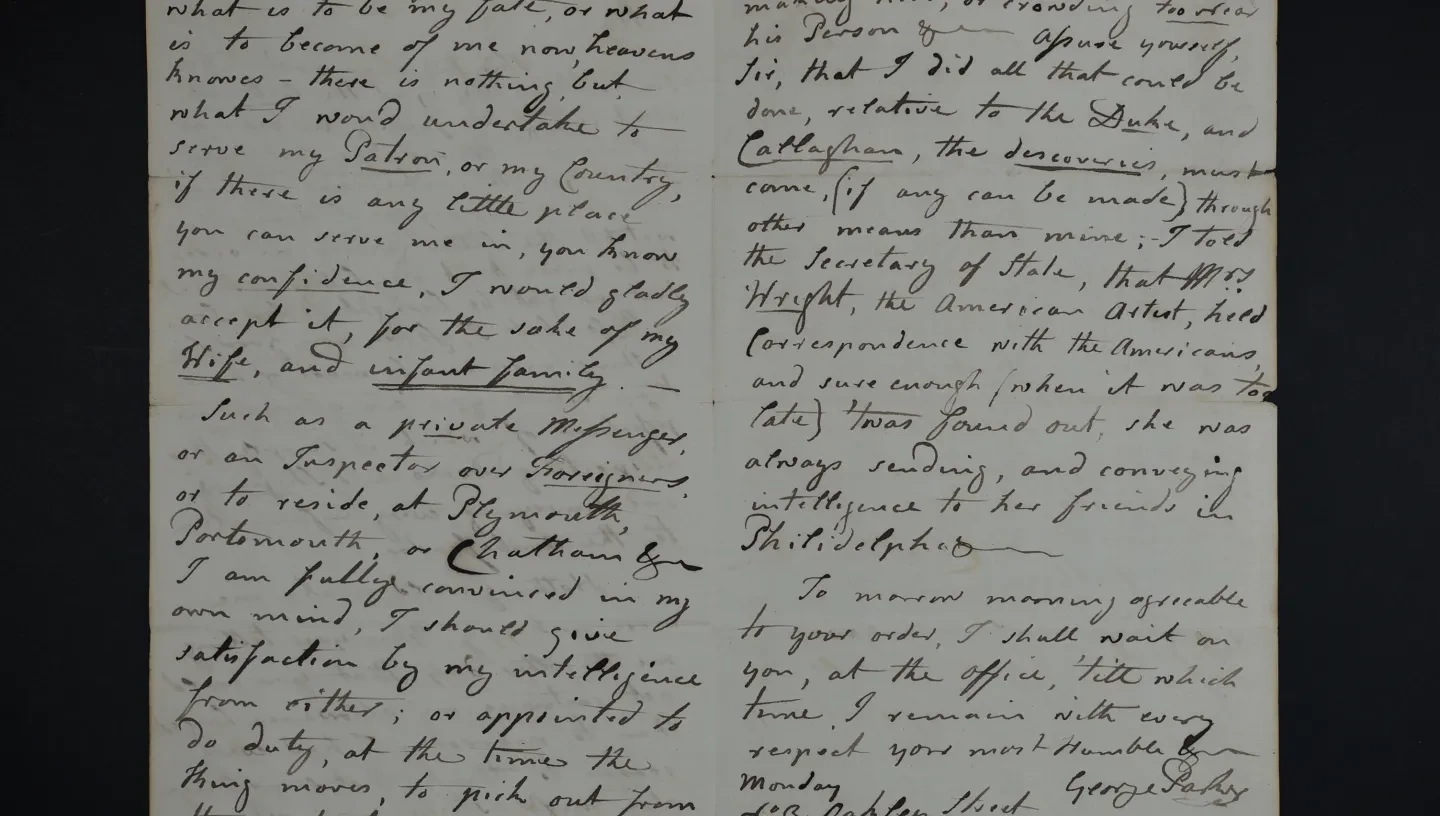

George Parker

Born in 1732, George Parker had an extensive career. He served in both the Army at Quebec and the Navy. Fluent in both Portuguese and French, he later became a travelling actor and lecturer before being employed by Nepean as a spy. His spying career, however, was a bumpy road. He was employed in 1790 to spy on the Venezuelan revolutionary, Francisco Miranda.

This surveillance could have been completed in a few days, but Parker admitted spinning out his surveillance for six weeks. He had also been employed to spy on other figures such as the Duke of Orleans, a man by the name of O’Callaghan, and Mrs White (an American artist who was passing on intelligence in letters addressed to Philadelphia).

As time went on, Parker proved to be unreliable. He appears to have been a heavy drinker and to have boasted of his secret employment. When the popular radical societies such as the London Corresponding Society sprang up in 1792, Parker offered his services only to be turned down once again by Nepean.

Though Parker pleaded for financial relief to help support his wife and child when he claimed to be too ill to walk across his room, he was never employed again by Nepean. He ended up in Fleet Prison where he met Thomas Smith Murray, a man claiming to be the illegitimate child of Prince Frederick. Thomas had sent letters to the Treasury, from the late Prince to his mother, which supposedly proved the claim.

On Nepean’s investigation of this, he found that the Treasury had passed the letters on to the King who had since ‘lost’ them. For making these claims, Murray was sent to Fleet Prison by Evan Nepean. It was there that he met Parker. The two seem to have bonded over how they had been treated by Nepean.

Francis Drake

Francis Drake was a British diplomat, holding positions at Genoa and Munich during the Napoleonic Wars. His title of diplomat gave him good cover for his role as spy setting up networks of informants. Some spies, including diplomats within the Home and Foreign Offices, used encryption and codes to conceal messages.

Members of the military and other agents were not entrusted with codes and simply hoped their letters were not intercepted. However, this did not stop some of Drake’s letters being intercepted by the French Government in 1804 before being circulated. In the letter on display, which is partially encrypted, Drake states that the city of Genoa, Italy, where he is based, is in a terrible crisis as a result of the French Revolutionary War, 1792–1802.

The display shows a selection of items in the Caird Library and Archive’s collection which relate to the world of spies as seen through their own words.

- NEP/3 - Secret Service Admiralty account book kept by Charles Wright and signed by Evan Nepean, 1785–1804

- NEP/9/1/4 - Letter to Evan Nepean from George Parker, 6 May 1790

- AGC/24/3 - Letter to Evan Nepean from Thomas Augustus Smith Murray, 25 September 1792

- CRK/4/108 - Letter to Horatio Nelson from Francis Drake, 29 March 1796

Spies: the Georgian secret intelligence service is on display until 21 July 2023.