Discover records relating to the Women’s Royal Naval Service in this new Caird Library and Archive display, February - June 2018.

by Mike Bevan, Archivist

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Representation of the People Act, 1918. One of the main contributing factors that led to the passing of the Act was the success of women in wartime, working in roles usually carried out by men, and the respect and admiration that this won them. The Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) was one such area of work during the First World War.

The Act granted the vote to some women over the age of 30 who owned property and also enfranchised men over the age of 21. The women’s Suffrage Movement found success in the 1918 Act but had to wait another decade for the Equal Franchise Act of 1928, which enfranchised women over the age of 21, giving them the same voting rights as men. Leading up to the First World War, suffragists and suffragettes had raised injustice to women as a serious political issue to address and much credit belongs to them.

Following is information on the items displayed:

Extract from a draft document written by Katherine Furse (1875–1952), Director of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (25 January 1918). Item ID: DAU/26

‘…it is essential to success that we should prove that women are useful and it is in no way part of our duty to try to prove that women are equal to men for they are not in stamina or physical strength. This is shown by the fact 4 women are considered necessary to replace 3 men…We are particularly determined that service in the WRNS shall not in any way be used towards feminism or politically towards women’s votes.’

Here, Furse makes the crucial point that to be successful in the War, gender should not be marked so distinctly in the workforce. Proving that women were as useful as men at work played its part in pushing through the Representation of the People Act in 1918, granting votes for women for the first time. Interestingly, Furse did not want the WRNS to be used politically.

Photograph showing storewomen of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) sorting ships’ lamps at Lowestoft (1918). Item ID: DAU/181/2

The demand for WRNS personnel to enter into clerical work roles increased as men were released to fight in the First World War. The WRNS were employed in a whole range of office duties and other positions, including store work.

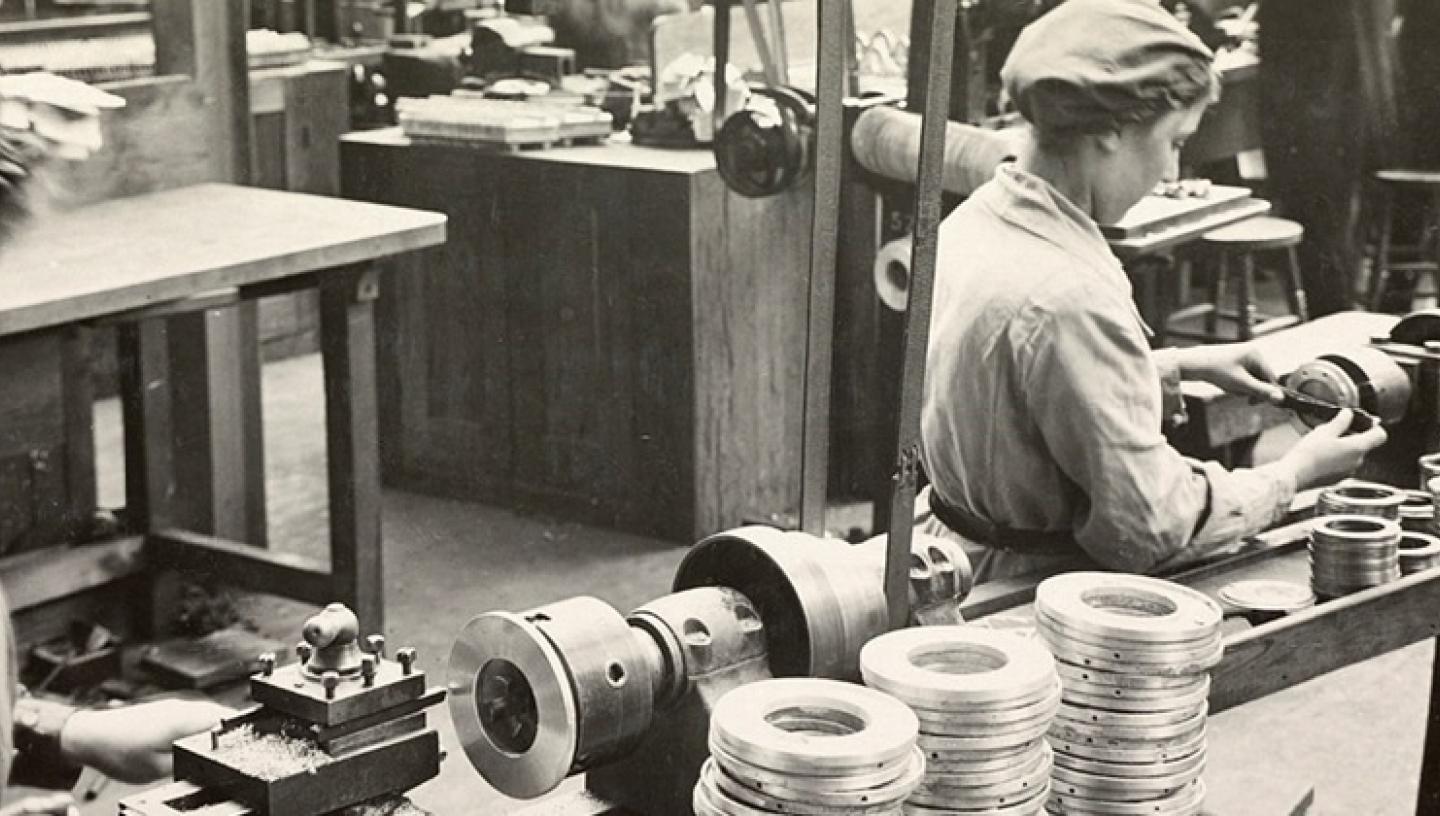

Photograph of a Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) rating assembling a mine (c. 1917-1919). Item ID: DAU/181/2

Three thousand women joined the WRNS when it began in November 1917. This figure was to more than double to seven thousand in 1919, while the different roles that members of the WRNS or Wrens (as they were popularly known) were trained in also increased. Their efforts received admiration and respect, as they fulfilled roles never previously assigned to women.

Pamphlet entitled ‘WRNS never at sea 1917–1919: the Wrens: being the story of their beginnings and doings in various parts’, published by the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) (1919). Item ID: PBN1327

Training for work in the WRNS was seen as a chance for a break from routine by one rating. This article reveals:

‘the first was escape from the past, which had held much responsibility…for it is nothing to be responsible for oneself alone having been responsible for countless others! And for three splendid weeks I was not unduly responsible for anyone but myself’. A second ‘escape’ was that ‘we were freed of our old shackles which left us absolutely free for flight.’ The article is signed ‘R.W’.

Extract from a speech delivered by Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) at Kingsway Hall, London (30 November 1914). Item ID: WHI/201

From the outset of total war, women played a major part in the war effort. The role that the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) played from 1917 until it was disbanded in 1919, is testament to this and helped define the political landscape prior to the passing of the Representation of the People Act in February 1918. The WRNS was revived in 1939 at the beginning of the Second World War.

‘What is it we lack in this country? A system of training women for various trades. Now, one of the results of this war is that for the first time there is an organised attempt to train women.’