How did naval victory and urban entertainment come together in this mid-eighteenth century painting?

By Katherine Gazzard, Collaborative Doctoral Partnership student with RMG, National Portrait Gallery and University of East Anglia.

Located on the south bank of the Thames, Vauxhall Gardens were a leading venue for public entertainment in mid-eighteenth-century London. Fashionable visitors seeking respite from the capital’s noisy, smelly and dangerous streets came to the gardens on summer evenings. They would stroll amongst the tree-lined avenues and elegant pavilions. As they did so, musical performances, masquerades, illuminations, paintings and sculptures entertained them.

In May 1762, a new artwork was unveiled at the gardens. A massive painting, measuring fifteen-foot across, it celebrated British naval supremacy. It also titillated the crowds. It depicted the spectacle of naked female sea nymphs embracing the portraits of well-known naval heroes. Created by the artist Francis Hayman, the original painting no longer survives. However its appearance is recorded in an engraving by Simon François Ravenet. The National Maritime Museum holds an early impression of Ravenet’s print. From this we can explore the eccentric imagery and sexual charge of Hayman’s lost work.

The Seven Years’ War

Known as The Triumph of Britannia, Hayman’s painting was produced during the concluding phase of the Seven Years’ War. This was a conflict between the dominant European powers of the period - principally Britain and France from May 1756 until February 1763. The British suffered defeats and set-backs during the early years of the war, but the nation rallied with a series of major victories in 1759. From this point, Britain remained in the ascendency. It was able to expand its territorial holdings in North America and India. This allowed Britain to firmly establish its dominance of the sea. Around 1760 , the gardens owner Jonathan Tyers commissioned Hayman to create four paintings. They were to commemorate the nation’s success in the war. The ideas was to turn military conquest and naval triumph into sources of fashionable entertainment. One of these paintings was the Triumph of Britannia.

Celebrating British Naval Supremacy

In the background of the Triumph of Britannia, Hayman depicts one of the most notable British naval victories from the Seven Years’ War. Here we can see the victory of Admiral Edward Hawke’s fleet over the French at the Battle of Quiberon Bay on 20 November 1759.

Against this explosive backdrop, the artist uses mythological figures. These symbolise British supremacy over the seas. Britannia – the traditional personification of the British nation – is shown being pulled through waves in a chariot driven by the Roman god of the sea, Neptune, holding a trident. In her lap, she held the medallion portrait of George III, who had ascended to the throne in October 1760. The chariot was attended by sea nymphs, trumpet-blowing tritons and bug-eyed sea monsters. Appearing like a triumphal procession, the scene represented national naval prowess. The whole event is presided over by royal authority in the form of George III.

Naval Portraits

With its classical gods, nymphs and tritons, The Triumph of Britannia employed a long-established artistic language. It looked back to ancient mythology and its revival in the Italian Renaissance. At the same time, one element within Hayman’s painting belonged emphatically to its own time. The sea nymphs carried portrait medallions of celebrated naval officers. In their mid-eighteenth-century powdered wigs and naval uniforms, these officers would have appeared to the work’s original viewers in the 1760s as men of the here-and-now. All of the officers depicted had distinguished themselves during the Seven Years’ War. Their names would frequently have appeared in newspapers of the time.

In most cases, Hayman based his portrait medallions on published prints. Members of the Vauxhall crowds would have seen these in print-shops. The portrait of Augustus Keppel is based on Edward Fisher’s mezzotint engraving after a portrait painted by Joshua Reynolds. Keppel’s head has been reversed – like a mirror image. It is otherwise close to the mezzotint source, retaining the subject’s sideways gaze and double chin.

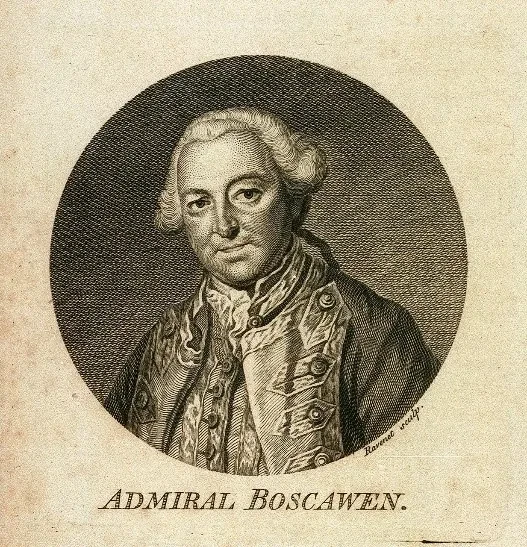

The oval format employed by Hayman for his portraits is reminiscent of the portrait medallions of the time. These were used to illustrate magazines and history books. For example, Ravenet created an image of Edward Boscawen, which was used as an illustration in Tobias Smollett’s The History of England, from the Revolution in 1688 to the Death of George II (1757). This was nearly identical to the medallion later included in Hayman’s picture. This demonstrates the cross-over between The Triumph of Britannia and popular literature of the period.

Because it used grand, classicising imagery and emphasised royal authority, Hayman’s painting could have been an exclusive and elevated work of art. Yet, by including famous faces and referring to well-known prints, the artist blended high art with popular culture. This created an image that was accessible and appealing to Vauxhall’s middle-class visitors.

Intimacy and Affection

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the Triumph of Britannia is the informal, emotional and sometimes intimate way that the nymphs interact with the naval portraits. For example, one suggestively caresses Edward Hawke’s portrait with her hand. Another has turned around to stare into George Anson’s eyes.

In stark contrast to the stately dignity with which Britannia presents the image of the newly crowned George III, the nymphs’ gently risqué behaviour titillates and entertains. This lightens the mood of Hayman’s picture in a manner entirely in keeping with Vauxhall’s playful and relaxed atmosphere.

When the painting was unveiled at Vauxhall Gardens in May 1762, a lengthy label was hung underneath it to explain what it represented. Evidently, there was some concern that viewers would be confused by the eccentric combination of mythological characters, naval battle and modern portraits! Today, the picture does not seem any less bizarre but it is also amusing. It reminds us that commemorating naval victory in the eighteenth century could be fun as well as serious.