When browsing the shelves in the library you occasionally come across a title or name that makes you want to investigate further. One such title that stood out for me was an account of the unusually named Captain William Death and his final voyage as commander of the Terrible privateer operating from London during the Seven Years War.

by Mark Benson, Library Assistant

Visit the Caird Library and Archive

This title can be found on our library catalogue as A genuine and faithfull narrative of the unfortunate Captain William Death Commander of the Terrible Privateer, written by Joseph Hart and two other mariners who served under Captain Death. Published in 1757 this was an attempt to provide an account of the Captain and crew’s bravery and to raise funds for the families of those who were lost. Beyond the account of the voyage itself this short work also lists the names of around 93 members of the crew and contains a 22-verse song composed whilst the crew were in French prisons.

As I searched for further information I repeatedly came across an anecdote that the Terrible was equipped at Execution Dock, Commanded by Captain Death, Lieutenant Devil and had a surgeon named Ghost. As amusing as this collection of names may be I’ve not been able to find any contemporary references to Devil and Ghost and it appears to have originated in later accounts, but the rest certainly looks to have been true.

I

Come all you Britons of courage bold,

Listen and we’ll soon unfold,

How we behaved you soon shall hear,

On board the Terrible privateer.

II

Death was our commanders name,

From London, with good hearts we came,

And put to sea with a pleasant gale,

Over our enemies to prevail.

Advertising in newspapers prior to the voyage for a ‘Cruize against the French’, Captain Death appealed to ‘All gentleman sailors and able-bodied landmen, who are willing to try their fortune as well as serve their King and Country’ to join the crew. The Terrible, then lying against Execution Dock, was described as being of 300 tons, mounting 24 guns and carrying 200 men. Having finished preparations in London she sailed to Plymouth to pick up more men before beginning her voyage in late November 1756.

On 23 December in the early morning light they encountered a ship which immediately ‘tack’d and bore away’ with the Terrible giving chase. The other ship then showed her colours confirming she was French and fired her stern guns on the Terrible. A running battle then took place over a number of hours with both ships exchanging fire as the Terrible attempted to get alongside and board the French vessel. His ship having taken heavy damage the French captain eventually decided to surrender, ‘which prudent conduct … saved abundance of his men’s lives’. The vessel turned out to be the Alexandre de Grande sailing from Sainte-Domingue to Nantes, she was 400 tons, mounted 16 guns and had a crew of around 100 men. She also had large amounts of cargo and money on board along with two ladies travelling as passengers with their fortunes. The Terrible then set about escorting her rich prize back to Plymouth.

VIII

Whilst many a bold Britain fell,

On board our ship the Terrible,

We boldly gave them gun for gun,

‘Till blood out of our scuppers run.

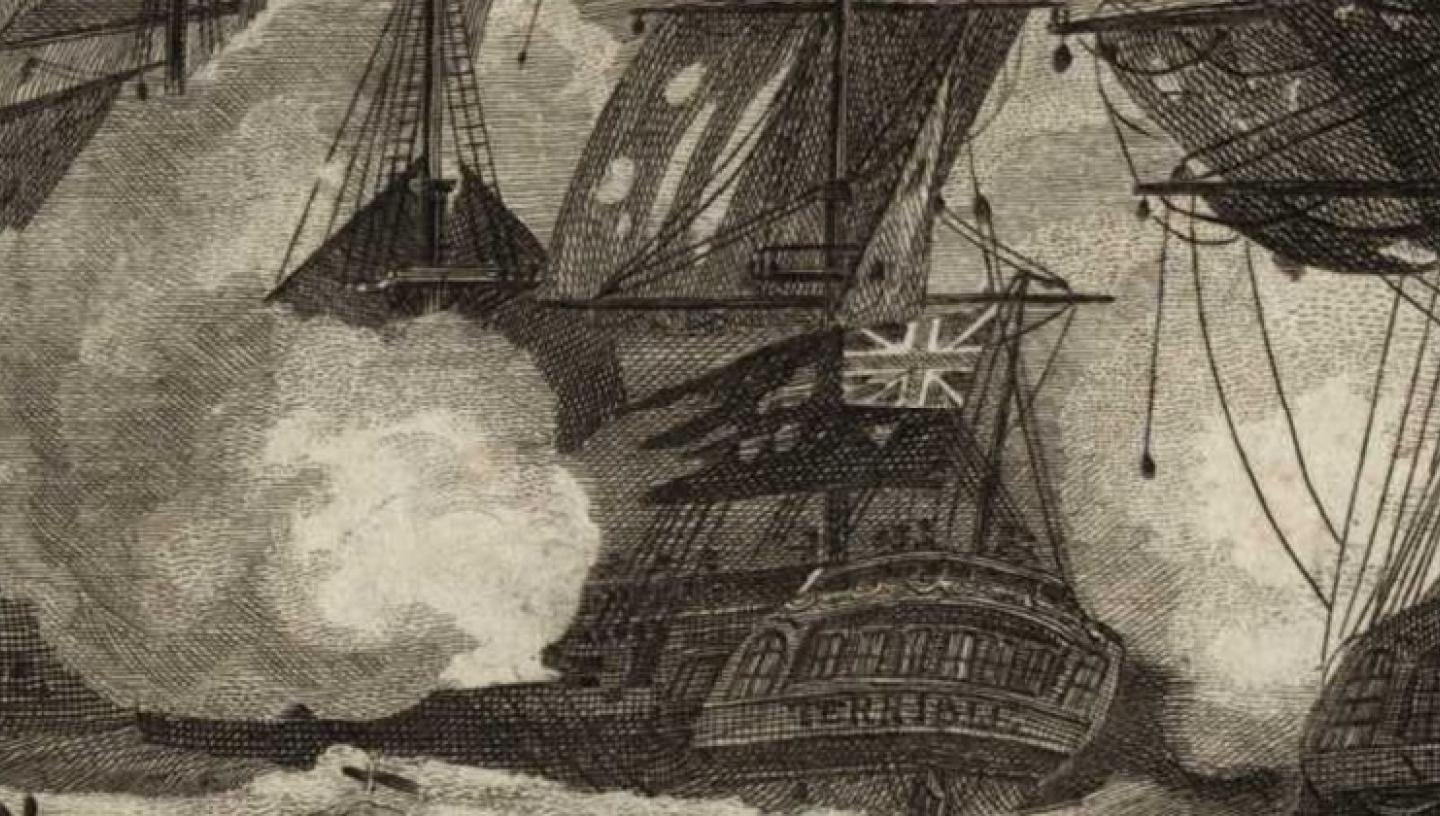

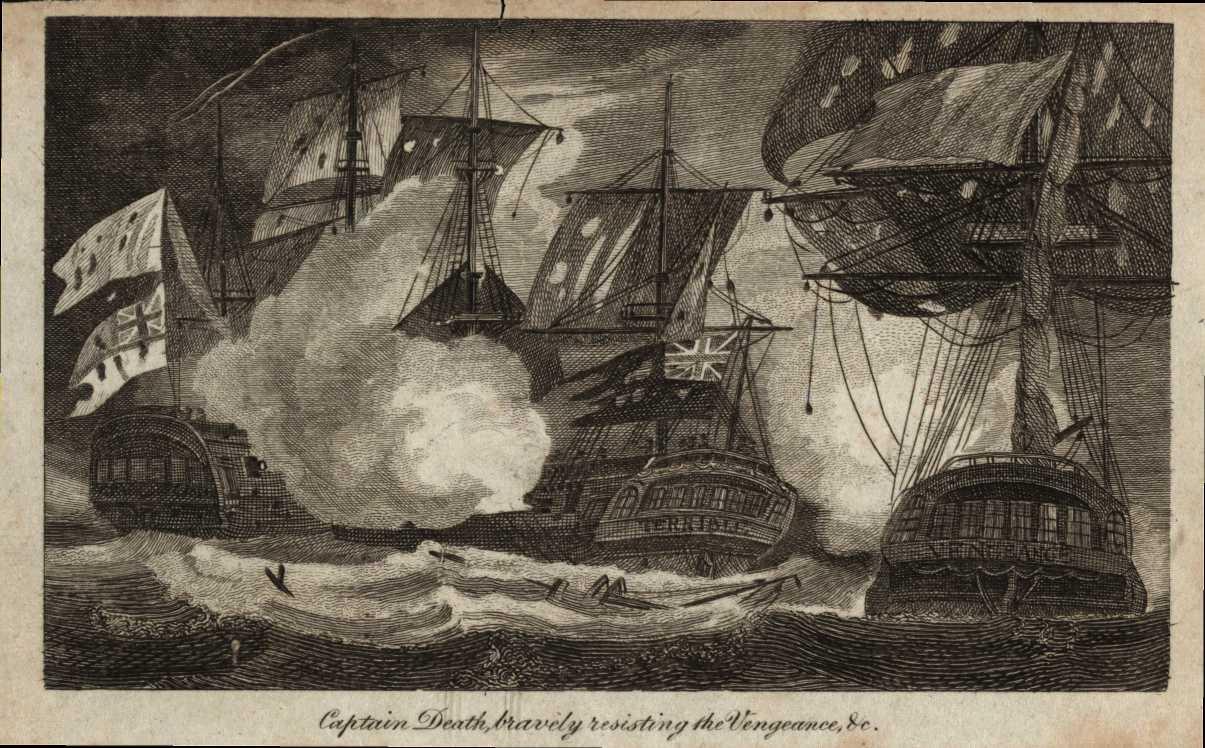

On 28 December they saw two ships in the distance that appeared to exchange messages, after which one began sailing in their direction. When the ship came into range it hoisted French colours and fired on them. This was the French privateer named Vengeance with 36 guns and a crew of 360 men operating from Saint-Malo. In the battle that followed the Terrible apparently became stuck between the prize and her larger, more heavily armed opponent with whom she exchanged broadsides for as long as she could, catching fire several times and losing her main mast. To add to their troubles she was also shorthanded with over 50 men who were noted as being ‘sick in their hamocks, at the time of our engagement.’ The Vengeance also had a large number of men positioned in the rigging who poured musket fire onto the unsheltered crew on the deck of the Terrible ‘like hail stones in a hard shower.’ Captain Death and his crew fought back as best they could with the author noting ‘she was afraid to board us, for we gave her such a warm reception for the short time that our few men lived, for such of our great guns as we could do any good with, we loaded with cannister and grape shot’ causing large numbers of casualties on the French side.

Eventually Captain Death was struck by a musket ball in the chest which exited through the small of his back, and having been carried to his cabin apparently ordered his remaining men to surrender. Accounts differ on whether he then died of his wounds or was later shot by the French in the confusion of the surrender. The author described the deck of the Terrible as being so covered in dead and wounded as being ‘enough to shock the stoutest heart in the world’ . The shattered remains of the Terrible were taken back to Saint-Malo with 26 men said to have survived the battle to be taken prisoner in France, of whom 16 had lost an arm or a leg. On the French side the Captain and almost two thirds of his crew were dead or injured.

XX

Now to conclude and make an end,

No truer lines were ever penn’d,

But since please God, we are got free,

The Terribles cause reveng’d shall be.

XXI

What tho’ our valiant Capt. Death,

To our great loss resign’d his breath,

The Vengeance was his overthrow,

But with vengeance we’ll revenge the blow.

The battle was described by Gentleman’s Magazine as ‘one of the most desperate and bloody engagements ever known’. London merchants opened a subscription at Lloyd’s coffee house in aid of Captain Death’s widow and his crew’s families. The memory of the battle clearly endured for a time, with Thomas Paine writing almost 20 years later in his pro-revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense using the example of Captain Death and the crew of the Terrible in his argument for how the Thirteen Colonies could produce a capable naval force recalled that with only 20 trained sailors from a crew of 200 they had ‘stood the hottest engagement of any ship last war’.

The surviving members of Captain Death’s crew returned to Britain as part of a prisoner exchange in around August 1757. Some were reported as having joined the privateer Norfolk to try their fortunes against the French once again.

The Vengeance herself would be captured by His Majesty’s ship Hussar in January 1758 and spend the rest of her career in British service, so Captain Death and the Terrible were at least partly avenged.