For February’s item of the month I have chosen JOD/133 a logbook written by T.F. Miller, the gunner on the whaling ship ‘Erik’ which records a voyage undertaken in 1876 from Dundee to the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay between Canada and Greenland.

by Mark Benson, Library Assistant

The Caird Library and Archive contains a number of logs written by people on fishing or whaling vessels. Although whaling is a controversial trade that has largely ceased in the modern world, this item caught my attention due to the large number of photographs included within it which help to illustrate what life was like for mariners engaged in it historically. Miller was obviously a keen photographer and his log includes photographs covering all aspects of the voyage from daily life at sea to their many encounters with arctic wildlife and local Inuit.

The early part of the voyage was mainly spent trying to avoid the larger icebergs or becoming trapped in the ice as they made their way to the fishing grounds. Miller commented on how wonderful the fresh arctic air was and how they were ‘very cheerful at getting away from smoky, noisy, dirty Dundee’.

The main purpose of the voyage appears to have been to secure around 100 tons of whale related products, primarily blubber from which they would extract whale oil. Crew members would watch the surrounding water looking to spot whales surfacing for air. Boats equipped with harpoon guns would then be launched and they would attempt to locate and kill the whales when they next surfaced. Often this initial harpooning was followed by a chase that on one occasion lasted several hours:

‘As the morning went on fish were seen in all directions but there was a strong south wind blowing with a nasty jump of a sea on and the odds were against the boats getting a chance. However all hands were called and the boats sent away and after waiting a long time fish came up near old James the 2nd mate, it was just sinking away as he pulled up when he fired his harpoon right into the water and to his delight found himself fast.

She led the boat a regular dance before succumbing making for the shelter of a large berg where she lay until the ship came up and the noise of the propeller made her leave. Three more of the boats got their harpoons into her and just as the Captain was getting ready the rocket gun to give her a final dose three cheers announced her death.’

During the course of their voyage the crew of the ‘Erik’ caught at least eleven whales. Miller and the crew spent many hours ‘flenching’ (removing the blubber) before cutting it up into blocks ‘about the size of a bar of soap’ which were then stored in tanks in the ship’s hold. With the ‘Erik’ apparently having had an extremely successful season they had to move the coal used to power the ship’s auxiliary steam engine into the crew’s berths and even onto the deck to make room for storing their catch. Miller later complained about coal dust getting into the chemicals he was using to develop his photographs.

Perhaps surprisingly given the work he was engaged in, Miller also occasionally noted the negative impact human activity was having on the wildlife in the region such as less birds being found than in previous years or when they reached an area he believed to be a kind of nursery for whales he wrote that ‘it was a bad thing for the interests of the fishery that ships ever found their way up here’. Despite this, Miller’s other great interest was clearly hunting and whenever they encountered wildlife from small hares to polar bears he and the crew invariably attempted to track and shoot it. Their first encounter with Walrus which he referred to as seahorses was fairly typical of this:

‘When we reached them we found that the Captain had harpooned a big bull sea horse (the gun breaking away from the pivot and kicking back) and in getting to the spot I found the brute hauled right up on the top of the water and the Captain quickly potting at him with express bullets which did not seem to make much impression. The harpoon was buried deep in his chest and twisted and bent like a piece of wire. I put a solid bullet from my rifle behind the head which seemed to finish him and with a good deal of trouble we had him on the ice…’

At various points in their journey they encountered local populations of Inuit whom he referred to as ‘natives’ or ‘Huskies’. They always seem to have been keen to go on board the ship and trade items, primarily animal skins, with the crew.

‘A good many natives came to see us in their kayaks and went away happy with salt pork and other good things. It is a very pretty and interesting sight to see them skimming over the water in their canoes looking most thoroughly happy and at home.’

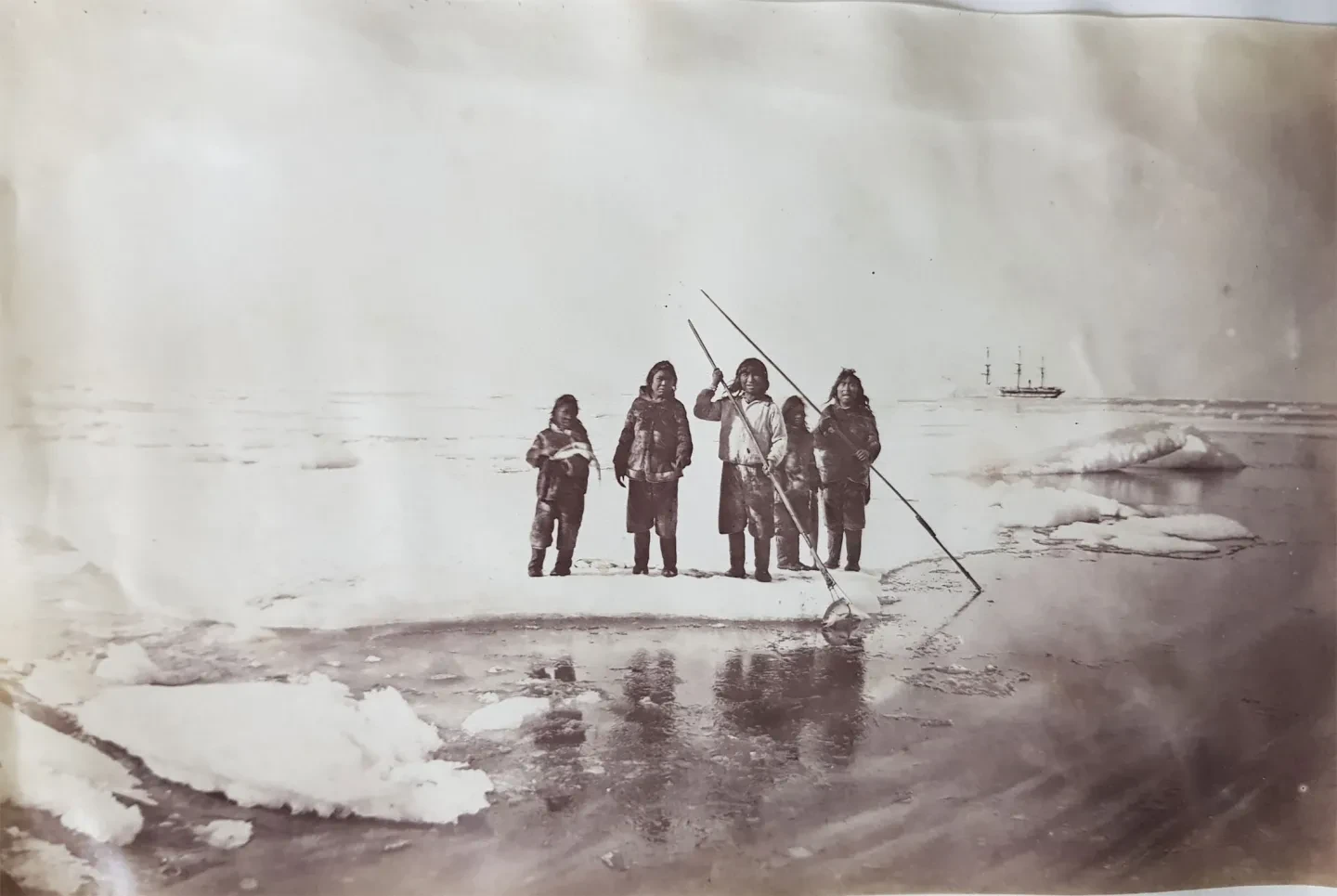

Miller also seems to have been interested in them and made several attempts at taking photographs that would display elements of their way of life:

‘Took the photographers shop ashore and with the captain’s help took two good photos of Huskies on shore and spearing salmon on the ice. They are the same we have met before who have travelled up here before us. Of course they are all over the ship – especially the cabin driving the steward frantic. There are a whole lot of them at the present moment leaning round the table looking at me writing and bothering me with questions in Husky which I don’t understand.’

Having spent over five months at sea and achieved their target they turned for home and reached Dundee on 29 October. The ‘Erik’ would continue her career at sea for a further forty-two years. In August 1918 with the crew having left the ship she was sunk by gunfire from a German U-Boat off Newfoundland.