As a young woman Emma Hamilton was one of the era's most celebrated beauties, enchanting aristocrats and artists alike. But how did other women fare in this age of pressure to conform to ideals of feminine beauty. Historian Emily Brand investigates.

Whatever the circumstances of her teenage life in London, Emma was fortunate to have been plucked from obscurity by an affluent lover and eventually immortalised by some of the country’s most prominent painters. In later life, even a rival was moved to proclaim that ‘the shape of all her features is as fine as her head, and…’ (perhaps a little oddly) ‘…particularly her ears’.

Prevailing ideals of beauty

"the ideal lady was slim and blonde, with broad buttocks, small breasts, a small nose, and red lips"

But what of those women not quite so blessed with a natural beauty? How might a woman whose income directly depended on her attractiveness seek to add to what was given to her by nature? In an age of (very) limited professional opportunities and often on a mission for matrimony, all women were under pressure to conform to the prevailing ideals of attractiveness. In 1722, ‘Thirty Marks of a Fine Woman’ declared that the ideal lady was slim and blonde, with broad buttocks, small breasts, a small nose, and red lips.

Fifty years later another helpful gent supplied his ‘capital points’ of beauty – after the depressingly obvious ‘youth’, we have ‘smooth forehead’, a plump chin, sweet breath, long or ‘prettily curled’ hair, and ‘two lips, pouting, of the coral hue’. Such attributes were obviously more easily achieved by those with a little money at their disposal, and those of ‘loose virtue’ were more likely to openly wear a painted face. But, in their quest for a husband, or a client, what advice did women actually follow?

Lead, mercury and boiled calf’s foot

"Acne could be treated with mercury pastes, or a homemade cure which involved boiling a calf’s foot in river water"

Books such as The Mirror of Graces (1811), which suggested how to preserve ‘beauty, health and loveliness’, give some clues. By this time a more natural look was in vogue. Skin needed to be fashionably pale, so respectable ladies were advised not to venture out without a parasol or bonnet, and that freckles could be washed away with lead lotions.

Acne could be treated with mercury pastes, or a homemade cure which involved boiling a calf’s foot in river water, adding bread and butter, and smearing it all over the face. For wrinkles, just rub pineapple or a raw onion over the face before bed. The hair could be washed with egg whites, rum and rosewater, before achieving a gloss with the grease made from unsalted lard, beef marrow and brandy. For white teeth, there were a variety of tooth pastes – some including charcoal, brick dust or a touch of sulphuric acid – followed by a rinse of lemon juice and claret.

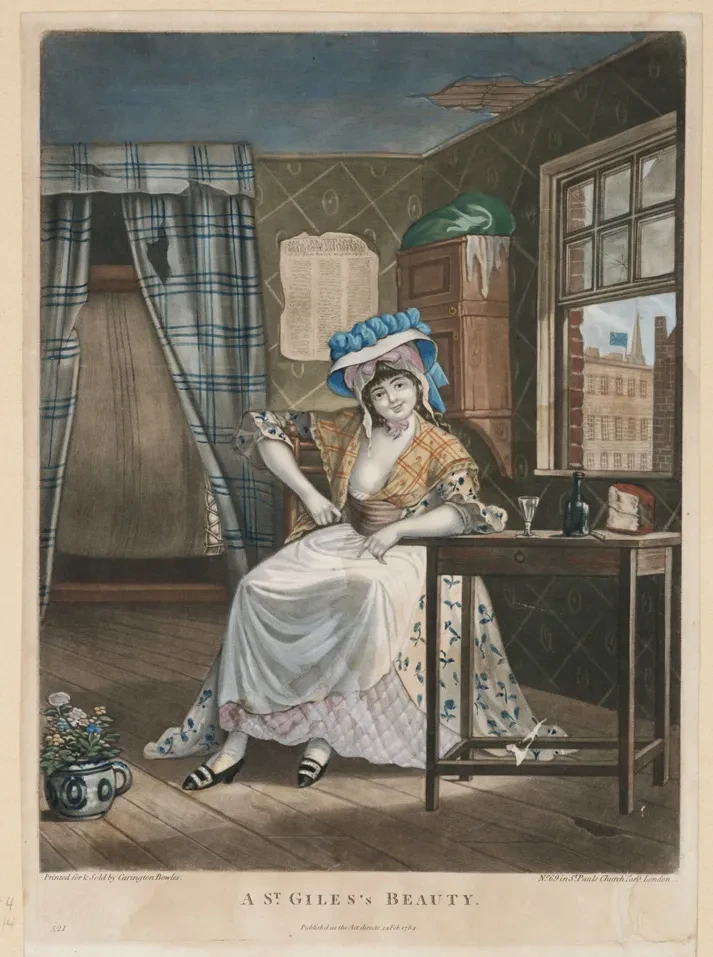

Trickery and titillation

Clearly, the possibilities for improvement were endless and as a result the very idea of such a mysterious beauty regime left men at once faintly terrified and oddly titillated. Though they feared that disease-ridden prostitutes and ageing crones could transform themselves into ravishing belles with a bit of make-up and a few false body parts, at the same time countless prints and poems of the day used the idea of a long process of beautification to give exciting intimate stolen glimpses of alluring young ladies en déshabillé. They were a testament to the cosmetic trickeries women practised, and cautionary tales for any men who might unwittingly attach themselves to an attractive lady, only to uncover her as a wretch in disguise the following morning.

Clearly, in the 18th century, fashionable society was not yet willing to embrace the idea that beauty is only skin deep – it could make or mar a woman’s life.

Emily Brand