In 1909, naval seaman Thomas Bouttell risked his own life to save a passenger who was fleeing a ship that was ablaze off the coast of Malta. For his bravery, he was awarded with the Royal Humane Society's Stanhope Gold medal, which was donated to the National Maritime Museum some 60 years later. The accompanying certificate is part of the Caird Library's manuscript collection.

By Katherine Oxley, Archive Assistant

The Royal Humane Society was established in London in 1774 by two physicians, William Hawes and Thomas Cogan, part of a wave of such societies that were springing up across Europe at this time.

It was originally called the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned, but by 1787, it was known as the Royal Humane Society, having secured the patronage of King George III in 1783.

The Society initially aimed to award those who had acted to save another person’s life, as well as to spread awareness of resuscitation and lifesaving techniques. It's activities were centred on London, but over time branches were set up around the country and in other parts of the world.

For a large part of its existence the Society was proactive in lifesaving activities, perhaps the most notable of which was the ‘Receiving House’ built in Hyde Park in 1835 (and demolished in 1954), where people who had been rescued from drowning in the Serpentine could be attended to by volunteer first aiders.

During the winter months ‘icemen’ were employed as well, to assist skaters who had fallen through the ice.

Although the Royal Humane Society’s archives are held at the London Metropolitan Archives, our library and manuscript collections do hold some examples of the literature published by the Society, including a poster showing how to resuscitate a person who had stopped breathing, and a leaflet with instructions for swimmers on how to rescue a drowning person.

The Society also promoted swimming and lifesaving skills in young people, and awarded a silver medallion for ‘proficiency in swimming exercise with reference to saving life from drowning’. Today the Society is no longer actively involved in the promotion of lifesaving activities.

Initially the Society gave out cash rewards to people who had saved another person’s life, but these monetary awards were replaced by a selection of medals and certificates.

The range of awards has varied somewhat over the years, but for most of its history, its highest honours have been the classic trio of gold, silver and bronze medals. The most prestigious of these is the Stanhope Gold Medal, which was introduced in 1873. This medal is usually awarded only once annually, to the most deserving recipient of the Society’s silver medal that year.

The Museum’s medals collection has several specimens from the Royal Humane Society, including a rare Stanhope Gold Medal, which was awarded to Thomas Bouttell, a 21-year-old able seaman, in 1909.

It is in fact one of several medals belonging to Bouttell, mainly for his naval service, that were donated to the Museum in the 1960s.

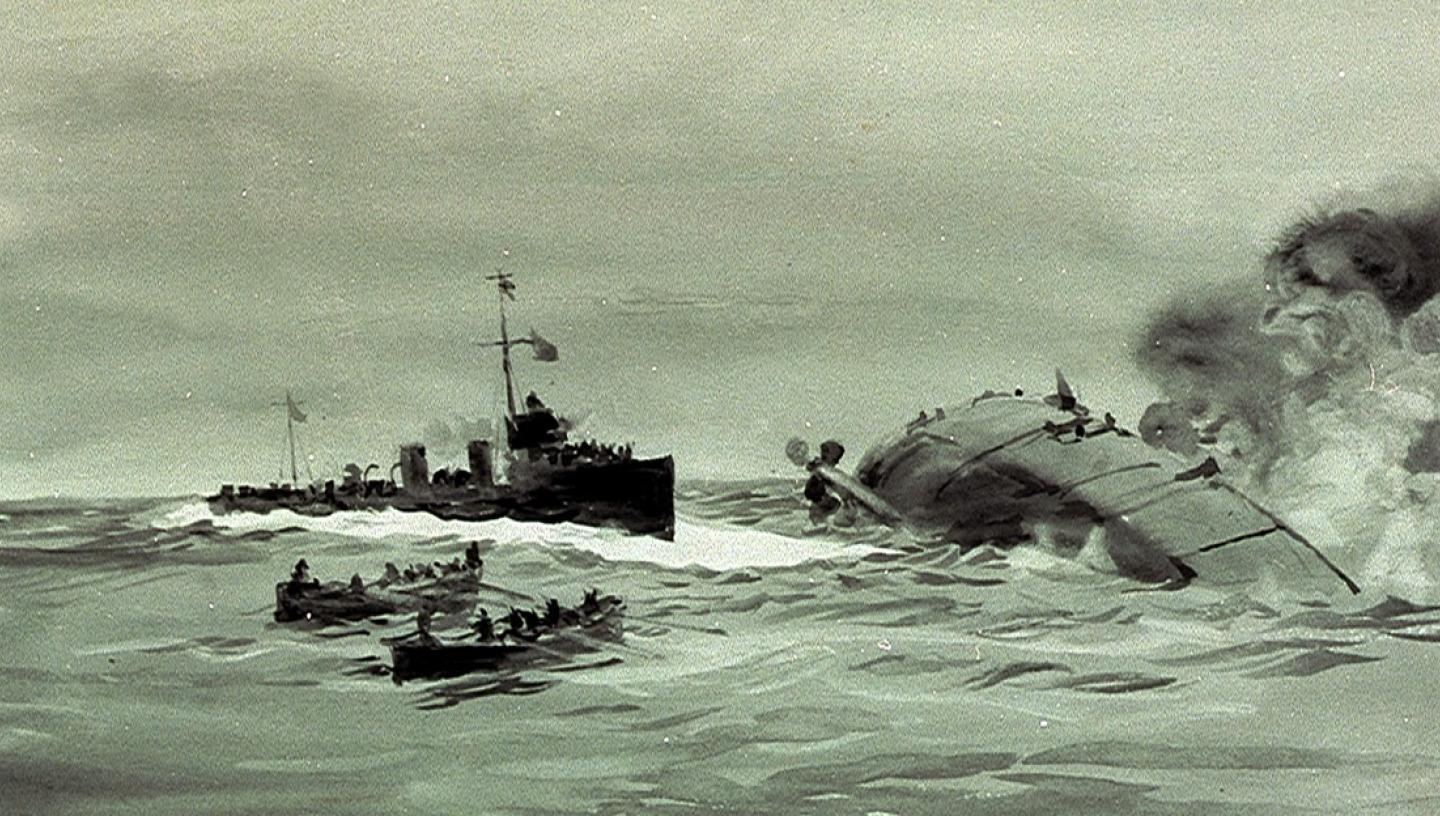

Bouttell earned his Stanhope Gold Medal for risking his own life to save one of the passengers from the British steamer Sardinia that caught fire off the coast of Malta on the morning of 25 November 1908, leading to the loss of many lives.

The Caird Library has a trilogy of books, Acts of Gallantry, which give an account of the brave deeds of each recipient of Royal Humane Society medals from 1830 to 2000 (RMG ID: PBP6876/1-3).

Volume 2, covering the period 1871 to 1950, includes an account for Bouttell.

He was part of a crew of 16 men from HMS Glory who were dispatched on a pinnace (small boat) to rescue passengers from the Sardinia. In heavy seas, they managed to help several passengers down into the pinnace with the aid of the rope, but one became entangled and was being thrown against the ship’s side:

A volunteer being called for, Able Seaman Thomas Bouttell sprang overboard, successfully detached the man from the rope, and supported him for a sufficient time to enable a customs whaler to pick them both up.

Great danger incurred, as there had been frequent explosions on board the ship up to that time; and owing to the fierceness of the flames in many places, the ship’s side was nearly red hot.

Our archives hold both certificates that he received to accompany his silver and gold medals. It appears that these certificates were much cherished as they were both framed.

We also hold several Royal Humane Society certificates belonging to William Dobbie, the first of which he received in 1828 as a teenaged midshipman on board HMS Ranger, for jumping from his ship on two occasions to rescue a drowning seaman.

His certificates are accompanied by a letter from someone we only know as ‘J. Tweed’, who was so moved by these acts of bravery that he penned some lines in Dobbie’s honour.

In his letter Tweedy presents his composition as ‘Verses addressed to W Dobbie Esq on board HMS the Ranger at Chatham who, by plunging into the sea, rescued two fellow creatures from drowning.’

Part of letter from J. Tweedy to William Dobbie with verses honouring his lifesaving deeds (RMG ID: DBB/109/2(2))

He wrote four verses, the second of which is shown below:

What Pleasure can the generous Heart possess

Equal to helping those, in great Distress

And who, but you, can say, what Joy to save

Two fellow Creatures from a watery Grave

Restor’d to Life, to Family, to Friends

The noblest Motive blest with noblest Ends

That Praise, that Joy is thine! Yes! Self-possest

For conscious Virtue rules thy generous Breast.