World War I might have ended for some in 1919, but for others fighting continued, whether they liked it or not.

The Armistice which came into force on 11th November 1918 is popularly remembered as marking the end of the First World War. Legally, the fighting between the combatants was formally terminated with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919.

After more than four years of bloody conflict and heavy casualties, weary service men of all nationalities could finally hope to return home.

For the Royal Navy, the end of the War meant a serious cutback in funding, arguably the most savage cut the Senior Service has ever endured in its history to date. In the 1918/19 Naval Estimates the government had allocated roughly £165,000,000 (about £9,240,000,000 today). In the 1919/20 Estimates this had dropped to a little over £50,000,000.

The Army suffered similar reductions, and the embryonic Royal Air Force, which had existed only from April 1919, simply struggled to survive in the cash-strapped post War Britain.

Worse for all three services, the end of the First World War did not mean an end to the fighting or Britain’s military commitments overseas. The War had left in its wake a world in a state of chaos.

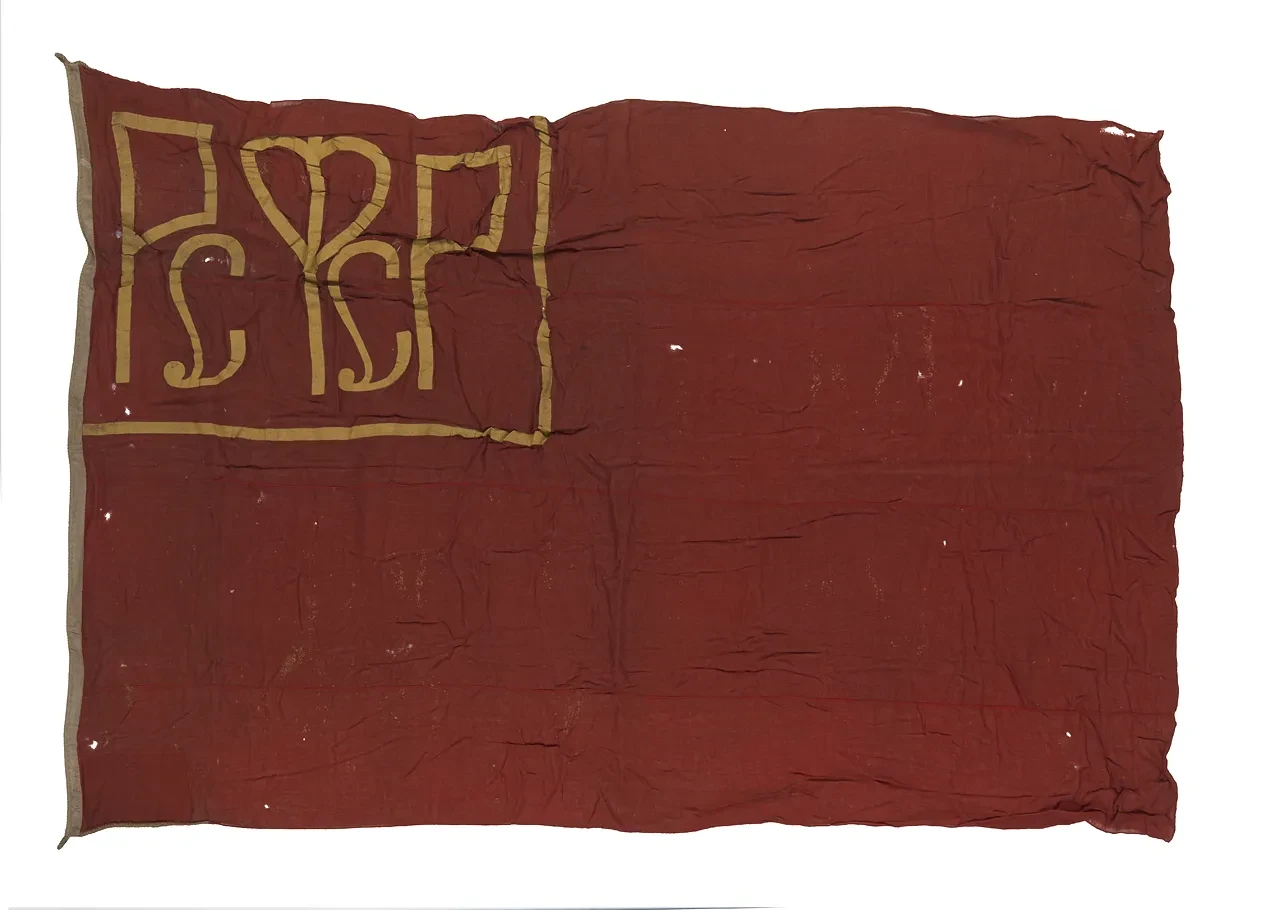

Britain’s primary concern was the maintenance of the empire she had fought so hard to preserve, and to contain any potential threats that might jeopardise her security as Germany had so recently done. The gravest external threat, and one in whom Britain and other nations were already embroiled in conflict, was communist Russia.

Communism as an ideology was viewed with much the same fear and loathing among the British ruling classes as anarchism had been a generation earlier. There were disturbing signs of social upheaval as numbers of returning British servicemen began demanding major political and social change as the price of their sacrifices for King and Empire.

Another area of concern was the Ottoman Empire. Weakened by heavy defeats in the Middle East during the War and under intense internal pressure from Turkish nationalists like Kemal Ataturk, the Sultan’s government was on the point of collapse. British plans for the future of the region depended on the presence of a stable if weak political entity, and British forces in the region were drawn into conflict situations as nationalist uprisings triggered armed ethnic conflict between the Ottoman Empire’s subject peoples in Asia Minor. Both theatres drew heavily on the Royal Navy’s now stretched resources, involving a heavy commitment of men and ships to the White Sea, Baltic, Black Sea and eastern Mediterranean.

As if these were not enough, the navy’s focus on the War in Europe and the Mediterranean had seen an increase in piracy, smuggling and slave trading in more distant waters, all of which needed to be addressed.

For the men on the ground (and indeed, on the water), many of whom had served through the difficult years of the First World War, these conflicts meant a long postponement of their anticipated homecoming.

Duty in the primary post-War hot spots could often involve great physical discomfort, especially for those operating in the cold of northern Russia and the Baltic. Climatically life was somewhat easier for the men in the eastern Mediterranean, but like their colleagues further north they suffered the frustrations of involvement in dangerous conflicts in which they had little emotional investment.

Operations in all these places primarily comprised supporting land forces ashore with naval gunfire and ensuring that the vital logistical support remained secure and functioning. In many instances, however, companies of Royal Marines and armed sailors had to be landed for combat operations or simply to help preserve order ashore.

In the Baltic, the presence of significant naval forces under communist control led to a series of clashes with the Royal Navy. On paper the communists enjoyed a great preponderance of strength in warships, but fortunately for the British this was offset by their lack of familiarity with naval warfare which led to a generally defensive mind-set, punctuated by occasional raids. In between these arduous duties, the men were generally subject to the necessary but monotonous realities of naval routine. Opportunities for rest and recreation ranged from adequate to almost non-existent, and it is not altogether surprising that some commands in the Baltic reported that their crews were in a state of near-mutiny. Dissatisfaction with their commander, Admiral Cowan, did lead to breaches of discipline on some ships in 1919. Given the close proximity of communist agitators, lower deck dissatisfaction was understandably a concern.

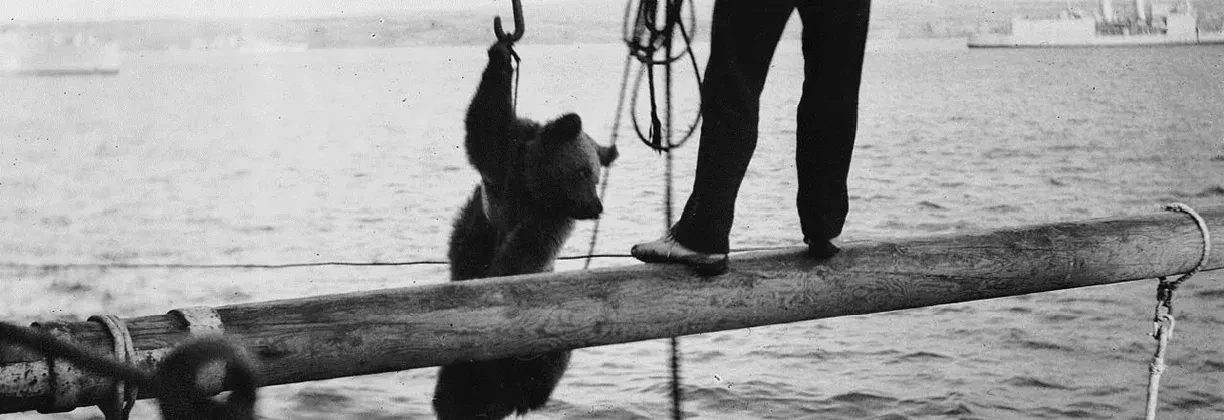

[N23913]: ‘Trotsky’ the bear being hoisted aboard HMS Ajax. Keeping pets (albeit mostly less extreme examples) was one of a number of ways sailors sought to amuse themselves during their off duty hours. ‘Trotsky’ was one of two bears known to have ‘served’ with British naval forces in the Black Sea.

The first of these theatres to be ‘closed down’ was the White Sea, as strong communist forces successfully drove back the ‘White’ Russian forces and their allies.

The British Dvina River Flotilla fought a successful rearguard action against hostile gunboats in September 1919, but in so doing was forced to scuttle two of its monitors to prevent their capture. A month later, the last British personnel left Murmansk.

In the year between November 1918 and November 1919 the Royal Navy fought a series of successful actions in the Baltic, but paid a heavy price with the loss of a light cruiser, two destroyers, a submarine and a myriad of smaller craft and 121 casualties. An elegant monument to these men still graces the old quarter of Tallinn, erected by the Estonians who perceived the British effort as a crucial element in their struggle for independence from Russia.

Operations in the Mediterranean and Black Sea faced little significant naval opposition, but the Royal Navy was kept busy with demands for inshore support of their White Russian allies. Between 1919 and 1922 the Royal Navy had the dubious distinction of evacuating members of two ancient royal dynasties (the Russian and Ottoman respectively) from territories where they were no longer welcome.

The Mediterranean Fleet was not able to resume regular peacetime operations until 1923, by which time the communist Russians had secured their Black Sea coastline and Turkey had emerged as a new state from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire.

The cost in lives of these operations is not possible to establish with certainty, but as we approach Remembrance Day a century on from 1919, it is worth bearing in mind that while the guns of the Western Front had long fallen silent, the conflagration which had swept Europe and the Middle East was still claiming victims on more distant frontiers.