With hundreds of observatories worldwide surveilling the sky, and extremely high-tech cameras zipping around the Solar System, you might assume there's nothing left in space for an amateur astronomer to discover.

Yet in 2022 three amateur astronomers and astrophotographers made a remarkable find in one of the most observed and photographed areas of the night sky.

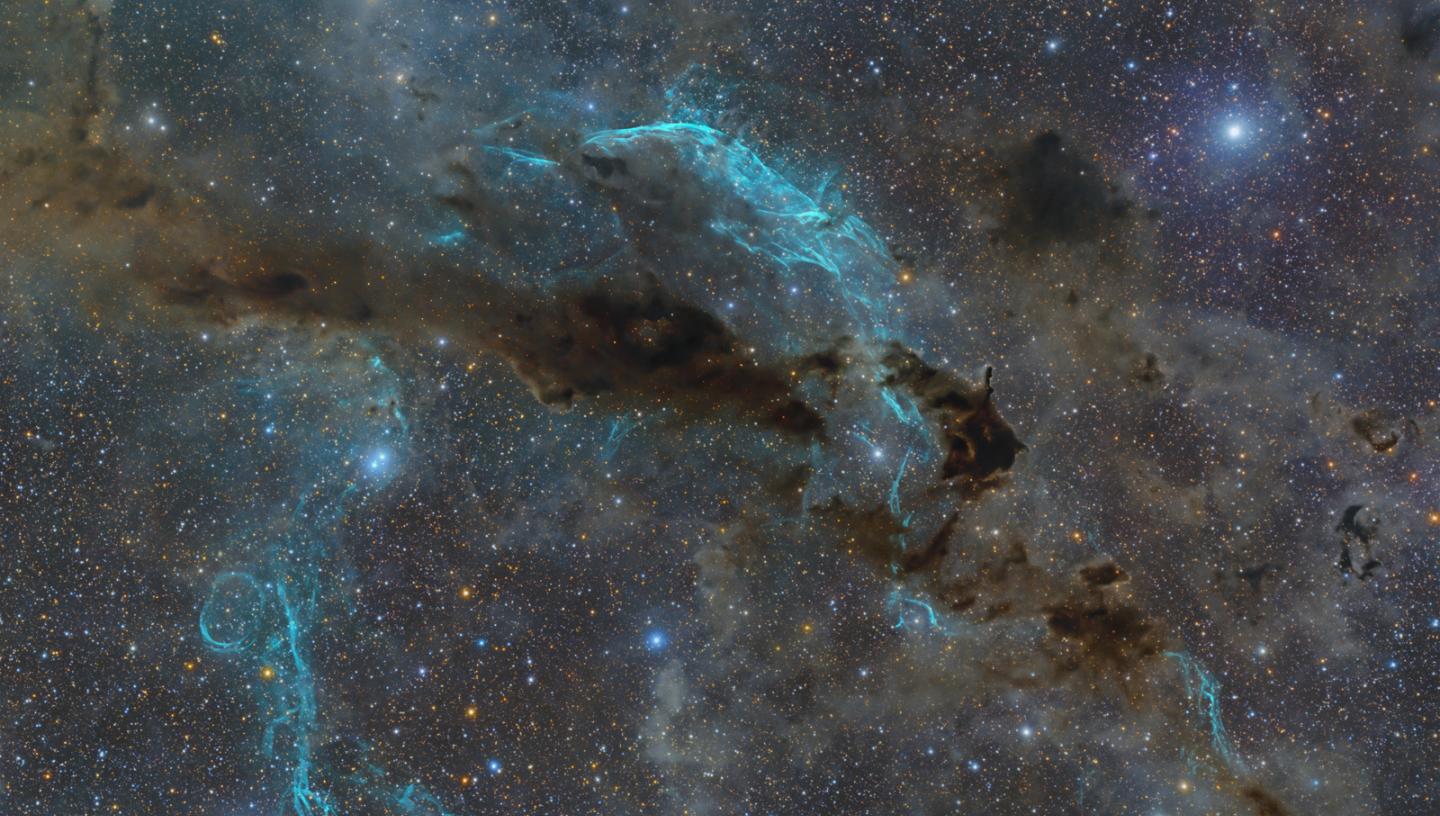

Marcel Drechsler, Xavier Strottner and Yann Sainty discovered and photographed a never-before-seen oxygen arc next to our nearest spiral galaxy, the Andromeda Galaxy.

The hours of hard work put in by these passionate amateurs earned them the top prize in Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2023, the world’s biggest space photography competition.

Competition judge László Francsics said of their image, “This astrophoto is as spectacular as it is valuable. It not only presents Andromeda in a new way, but also raises the quality of astrophotography to a new level.”

Learn more about their award-winning image.

What did the team discover?

The Andromeda Galaxy (also known as M31) is the nearest large galaxy to us at around 2.5 million light years away.

The earliest known photograph of Andromeda was taken over 130 years ago in 1888 by Isaac Roberts, and since then it has been a hugely popular target for astrophotography.

However, in 2022 the three astronomers and astrophotographers discovered a ‘huge plasma arc’ in its vicinity, recognisable as the slightly-curved blue cloud to the left of the spiral galaxy in Andromeda, Unexpected.

Firstly, what is plasma? Plasmas have some similarities to gases, consisting of freely moving atoms which, through high temperature or radiation, have become split from some or all of the electrons that make them up. The result is a soup of electrons and partially ionised nuclei which gives them some weird properties.

99 per cent of the visible universe is made of plasma; we can see it in the form of stars, nebulae, solar wind, comet tails, the aurora and more.

“What you see is gigantic blue arc of ionised oxygen gas that has never been seen before,” amateur astronomer and astrophotographer Marcel explains.

The arc is an ‘emission nebula’, which is a cloud of ionised gas that emits its own light at an optical wavelength (I.e. UV, visible or infrared). Stretching 1.5 degrees across the sky, it appears to be almost half the size of the Andromeda Galaxy.

“As a result, it could be the largest and closest such structure to us in the Universe,” the team wrote in their application to Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2023.

The arc has now been named the Strottner-Drechsler-Sainty Object 1 (SDSO-1). Scientists worldwide are collaborating to investigate the arc further, including its potential relationship to its neighbouring galaxy.

Why hasn’t this been seen before?

“Over 100 years, nobody has seen the arc because it's so faint and it's only visible in Oxygen 3 (OIII),” Marcel explains.

When gases like hydrogen, sulfur and oxygen are superheated they glow in various colours, with oxygen giving off a blue colour.

Telescope narrowband filters allow astronomers to look at the light from certain gases, with the most common filters being Hydrogen Alpha, Hydrogen Beta, Sulfur 2 and Oxygen 3.

As three quarters of gas in the Universe is hydrogen, astrophotographers tend to take photos using a Hydrogen Alpha (Hα) filter in order to see this type of light.

Oxygen, by contrast, makes up just 1% of gas in the Universe and is extremely faint, making it difficult to see.

Photographs taken with an Oxygen 3 filter are also subject to distortions from factors such as light pollution, meaning fewer astrophotographers choose to use it.

However, for those willing to put in the long exposure times required to take photographs in Oxygen 3, many discoveries await.

“The arc is not very easy to capture. You have to be an ambitious astrophotographer to catch this arc,” Marcel says.

Bright oxygen clouds have already been discovered in other nebulae such as the Veil Nebula, where oxygen gas is heated, ionises and glows blue.

An unexpected discovery

So how did the team find it? Marcel explains: “It was an absolute accident. No one expected to see it and that's why it’s called Andromeda, Unexpected, because we wanted to take a beautiful image of the Andromeda Galaxy. And we looked at the first data and we spotted this hazy smudge on the edge of the image.”

The astrophotographers originally thought the smudge could be an ‘artifact’, an anomaly or distortion which shows up on images due to interference from things like light pollution, satellite trails and scattered light.

After much discussion, however, “we came to the conclusion no, it's not an artifact. It's real. It's a new discovery,” Marcel says.

But why haven’t any of the extremely sophisticated cameras up in space spotted this? Essentially, while space telescopes take extremely valuable photographs, they have limitations in their scope.

“We amateur astronomers can capture what Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope can't because they only capture a teeny tiny fraction of the sky,” Marcel explains. “With our small and not-so-expensive telescopes, we are able to capture a wide field image of the night sky.”

“We are faster than Hubble, we have a wider field than Hubble, and we can do more exposure times than Hubble. When you have a very tiny, bright nebula, you call Hubble, but when you have a very faint big object in the Milky Way, you call us amateur astronomers.”

He explains that thanks to increasingly sophisticated equipment available, amateurs can act as the eyes and ears of professional astronomers due to their passion, dedication and time.

How did they take the photo?

Each member of the team brought their own specialisms to the table to create Andromeda, Unexpected.

Marcel explains: “Xavier is a very good researcher and analyst, and Yann is doing a great job in capturing the data. My part is the image editing; I'm taking the raw data and I'm making a beautiful image out of that.”

According to amateur astrophotographer Yann, “It’s a sharing of knowledge which results in everyone learning new things.”

Firstly, Marcel and amateur astronomer Xavier discovered a potential planetary nebula, and they commissioned Yann to shoot the data.

Yann wanted to experiment and shot Andromeda with a special filter, hoping to discover a planetary nebula. But what Marcel and Xavier discovered in the data exceeded their expectations.

Yann took photos of Andromeda using a range of filters. Upon sending the data to Marcel and Xavier, they noticed something very faint that merited further investigation.

As a result, over 22 nights, Yann diligently captured around 110 hours of data in various filters with a range of exposure times.

Weather was an issue; Yann had to follow the weather from the north to the south of France, travelling each day to various locations that would allow a clear sky that night.

5,000km travelled

An approximate route taken by the astronomers to capture data

Stacking Yann’s images taken with various exposure times allowed the team to create a ‘median’ image, toning down the noise from individual images. It also allowed them to filter out other blue-light emitters that were showing up in the Oxygen 3 filter.

Data from five other telescopes in France and the USA verified the presence of the oxygen arc.

Yann’s raw data was handed over to Marcel, who processed the image: “For me as the picture editor in the team, it's most important to combine the aesthetic of astrophotography with the scientific aspect and merge it together to make it a ‘wow’ image.”

Yann reminisces: “The first time we saw the image we were blown away, as much by the arc as by the detail in the galaxy.”

The importance of collaboration

For Marcel, Xavier and Yann, it was astrophotography that brought them together.

Marcel says, “Our group first met on the internet and since then we have worked together on projects remotely.”

The team became good friends during the process of discovering the arc, and learnt a lot from each other, despite living far away from each other.

“We have very much the same vision, the same values; it’s very enriching to work with people like this. It was a privilege for me to work with them and get their expertise,” says Yann, who is a relative newcomer to astronomy, having taken up astrophotography in 2020 during the coronavirus lockdowns.

The team working on the discovery has since expanded from the three photographers to include astrophysicists, astrophotographers and scientists worldwide.

This includes Robert Fesen, Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Dartmouth College in the USA, who was the scientific lead, alongside Professor Stefan Kimeswenger of the University of Innsbruck. Michael Shull, Professor of Astrophysics of the University of Colorado, and Professor Quentin Parker of the University of Hong Kong also provided scientific support.

Astrophotographers Bray Falls, Christophe Vergnes, Nicolas Martino and Sean Walker meanwhile provided astrophotography support.

“For me, the most important message is to work together in different languages, across borders, with an international community,” says Marcel. “To combine these skills and these people around the globe made this image and this discovery possible.”

What is the significance of the discovery for amateur astronomy?

This discovery reiterates the value of amateurs in the field, and astrophotography as both an art and a science.

Amateur astronomers “can say we are the eyes of modern research,” suggests Marcel.

“There are thousands of us, we have a lot of time, we have good equipment, and we are spread around the globe. It's the sheer number and the passion of us amateurs that makes the difference.”

For those with the time and interest in astrophotography, Yann advises people not to wait: “I would say to everyone interested in astrophotography to not hesitate to take it up. Try with whatever equipment you can. With a little bit of training and learning, it can be accessible to you. It opens up marvellous doors.”

Xavier adds: “To be able to have our name on this object forever, that’s a real legacy for the future.”

Marcel, Xavier and Yann would like to thank all the people who worked on the discovery: Professor Robert Fesen and Professor Stefan Kimeswenger (scientific leadership). Professor Michael Shull and Professor Quentin Parker (scientific support). Bray Falls, Christophe Vergnes, Nicolas Martino and Sean Walker (astrophotography).