Astronomy Photographer of the Year is one of the world’s biggest astrophotography competitions and has been hosted by the Royal Observatory Greenwich since 2009.

Thousands of photographers from all over the globe enter this competition every year, and with categories such as Best Newcomer, the Annie Maunder Prize for Image Innovation and the Young Competition, it is open to people of all ages and experiences.

The shortlisted and winning photographers and special guests were invited to a private view in September 2023, where they could see the Astronomy Photographer of the Year exhibition. During the event, Royal Observatory astronomers Affelia and Jess, with help from members of the Astronomy Ambassadors Group, recorded interviews with some of the photographers talking about their images and advice on how to start taking beautiful photos of the night sky.

Please be aware that you might hear some background noise from the event in the recordings below. If you’d like to see the exhibition yourself, it is open daily at the National Maritime Museum.

Interview #1: Miguel Claro, Angel Yu and John White

Interview #1: Miguel Claro, Angel Yu and John White

Interview #2: Derek Horlock, Joao Yordanov Serrhalheiro and Jonathon Lodge

Interview #2: Derek Horlock, Joao Yordanov Serrhalheiro and Jonathon Lodge

Interview #3: Mat & Benjamin Lawler, Feargus Casbolt and Harry Johnson

Interview #3: Mat & Benjamin Lawler, Feargus Casbolt and Harry Johnson

This interview was conducted by Petra, Lizzie and Varuni from the Astronomy Ambassadors Group.

Interview #4: Andre Vilhena, Martin Lewis and Lorenzo Ranieri

Interview #4: Andre Vilhena, Martin Lewis and Lorenzo Ranieri

Interview #5: Josh Dury, Peter Larkin, Dario Giannobile and Katie McGuiness

Interview #5: Josh Dury, Peter Larkin, Dario Giannobile and Katie McGuiness

Winner interview: Yann Sainty

Astronomy Presenter Mario also spoke to Yann Sainty who was part of the trio who won this year’s title with their photograph Andromeda, Unexpected. You can listen to their conversation in French in the recording or read the English transcription below.

Mario: So, first of all, Yann, would you like to introduce yourself?

Yann: Yes. So, my name is Yann Sainty. I'm 37 years old, so I live in France and I'm a web developer. And I've been doing astronomy and astrophotography for three years.

And what pushed you to do photography in general? First of all, how long have you been a photographer? So, photography in general. And then what led you to specialize in astrophotography?

So, it's a little bit special for me. I've never done photography before. I started directly with astrophotography. Before I started, I had never touched a camera. I had never taken a picture. So, I didn't specialise. It was by discovering astrophotography that I learned photography at the same time.

Okay, both at the same time.That's great. Yeah. So, astronomy, where does this passion come from? Did it come from your training or rather from a hobby? How did you get into it, really?

So, during the lockdown, during COVID, I was lucky enough to be in a house with a garden. And I wanted to spend time looking at what was possible to observe from his garden. So, at first, it was more about observation. So, I went to see on the internet and I bought some equipment. And to have fun, I tried to film what I was seeing with my phone. And since it didn't work too well, I looked on the Internet how to take better pictures. And that's where I discovered the existence of astrophotography. So, I started buying specialized equipment for astrophotography. And since then, I completely stopped observing to do only astrophotography. So, we can say that it was the conditions and the context in which I lived that made me want to start.

Okay. But you were an astronomer, an observer. Did you observe before or did you start with observation and then move on to astrophotography?

No, really, everything at the same time. I did observation for about a week. And I immediately wanted to immortalise what I was seeing to be able to share it. And so, it immediately went through astrophotography. So, I never really did observation.

Well, in any case, it's great. The result is magnificent here. I hope you will continue to immortalize beautiful moments in this way. And since then, did it make you want to immortalize other things, to photograph other things, or did you stay specialized in astrophotography?

So, no, it didn't make me want to take pictures outside of that. After that, it's also a matter of time, I think. Of course, astrophotography now takes up a lot of space in my life. And I know that if I start to be interested in something else and that I take a liking to it, it will take a lot more time. So, I prefer to focus fully on astrophotography, which I am passionate about, than to do something else.

Of course, I understand. Okay, so you talked a little bit about how you were trained. I have the impression that you were mainly trained alone in astrophotography. But speaking of the equipment, what importance do you give to the equipment you use? Do you need a superb last-minute camera, a telescope? How do you take it from a material point of view?

So, the equipment, it has its importance, of course, but it's not mandatory. You can do astrophotography with very few things, with a simple tripod, a camera, without a telescope, a camera lens, you can already make superb images of the Milky Way.

Then, for what is nebulae and deep sky, you just need a mount that compensates for the rotation of the Earth. But again, no need for a telescope or an astronomical lens. You can very well put a camera on a mount and take pictures of the deep sky.

Then, when you dig a little and you really take your time, the equipment becomes... So, it's not a limit, but it slows us down, let's say. When you start needing a lot of break time, etc.,you will look for equipment that is more efficient to go faster. So, the result is not necessarily significantly better in terms of quality, but you can do the same things much faster.

And when on objects like the ARCO 3 of the M31, you need 110 hours of break, a high-performance equipment allows you to go much faster to get that signal. So, the equipment is an advantage, we won't lie, it helps, but you can start having fun without having very big and very expensive equipment.

Okay, okay, that's great. That's what's great about astronomy in general, it's accessible to a lot of people. As soon as you start getting interested, you realize that with a smartphone, you can already start doing astrophotography.

Absolutely, yes, absolutely.

And about this photo, do you want to tell us a little bit more about how you took this photo? Did you plan it completely? Or are there certain elements of the photo that came by chance, because you were in the right place at the right time? Yes, if you want to tell us a little bit about the genesis, the conditions of this photo.

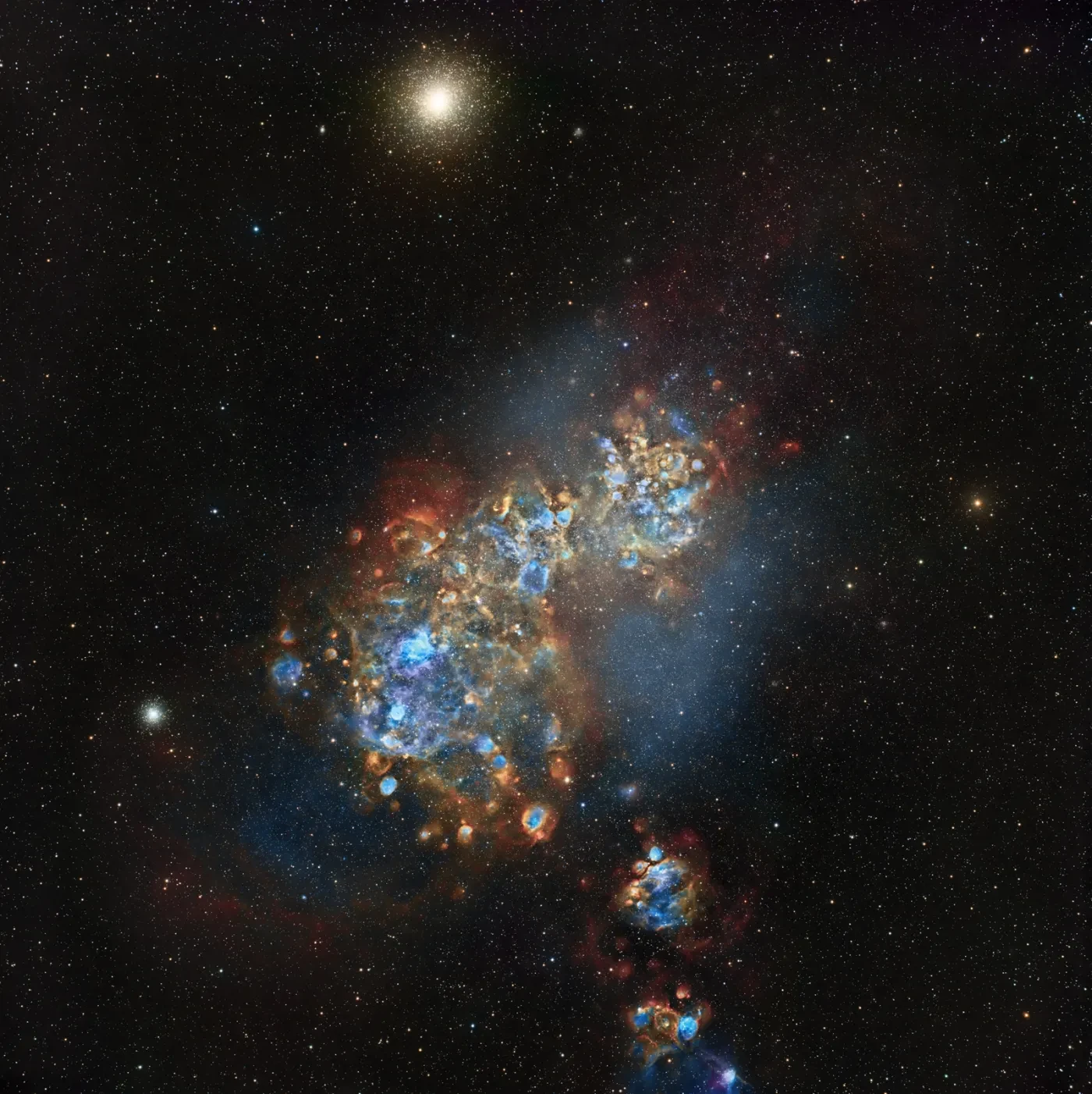

So, for this photo, it's really a team effort that allowed Xavier and Marcel to get there.

So, for the little story, Xavier and Marcel are recognized in the field, they do research, they discover planetary nebulae. And last year, they made a discovery and I shot it for them. And after that, it gave me a little taste for research.

So, what I wanted to do was use a filter that we don't usually use on the M31 galaxy. But my hope was to discover a small planetary bubble, so a few blue pixels on the image. So, I did the first tests that I sent to Xavier and Marcel.

And it's them in these images where they discovered the arc, this very diffuse area. And we thought, it's weird, it's huge, it's in one of the most photographed places in the sky. It's weird, so before even thinking about taking a picture, we're going to have to analyze the area a little bit.

I mean, I took pictures all around the galaxy, so we can study and see the size of the object. Then we had to make sure that the object existed, was real. And so for that, we went through other astrophotographers around the world, in different places, at different dates, saying to ourselves, if this little light area ever appears in different places in the world, at different dates, in different conditions, with different material, it means that it exists and that it's not a coincidence.

So we called, we contacted friends of mine, Christophe Vergne and Nicolas Martineau. Marcel contacted Bray Falls in the United States. And we got the pictures from everyone.

And once we saw that it really existed, Marcel was able to contact professors like Robert Faison, who took the scientific lead on the thing, because it went beyond astrophotography. There was a scientific side we needed knowledge about. And so once the professors said, OK, it's good, it exists, we were able to, by taking all the images we had taken of the area, define the optimal framing to make a beautiful image.

And while the professors were studying, we were shooting to take the picture, and we were sending the data in torrents. And so we were able to have our final image almost synchronised with the scientific publication of the professors. And that's how we got both an image and a scientific discovery.

OK, so it's really part of an idea, a little bit original, which is to take a different filter to observe M31.

That's right, there was a desire to experiment, to try something new. So it starts with a real intention, but there was a great deal of luck that this experiment, where we hoped to find a small bubble, gave something so huge.

A beautiful discovery with a lot of chance, which rewards a certain exploration in your approach to astrophotography. And then a beautiful collaboration between scientists, amateurs, professionals. And it also reminds me a little bit of the discovery of Uranus and Neptune, when something starts to be observed, we send it to colleagues in other countries to check that they are also observing it, or that with their knowledge they can make sense of this discovery, this potential discovery, or at least confirm it. And it often takes several people to make a discovery. It's beautiful, which is both the aesthetic side of photography, while having the discovery at the same time.

That's right.

Is there anything in particular that you would like people to remember? What do you hope people will remember from this photo?

For us, the most important thing is more than the image, it's the message behind it. If we try, anything is possible. You shouldn't be afraid to try things, to experiment.

You don't need immense knowledge, you don't need completely crazy equipment. It's really accessible to everyone. You just have to try, take time, accept to waste time, because it's a risk.

We were lucky that the trial worked. We could have done ten attempts, a hundred attempts, or even thousands of attempts, and it would never have led to such a big discovery. More than the image, it's the message to say that it's possible, that anyone, if they want to experiment, they have to go for it, and it can give beautiful things, and especially beautiful human adventures.

Okay, great message. You saw the contest, there are other photos in the contest. Do you have a favourite photo, or things that really marked you in this exhibition? Apart from your photo, of course.

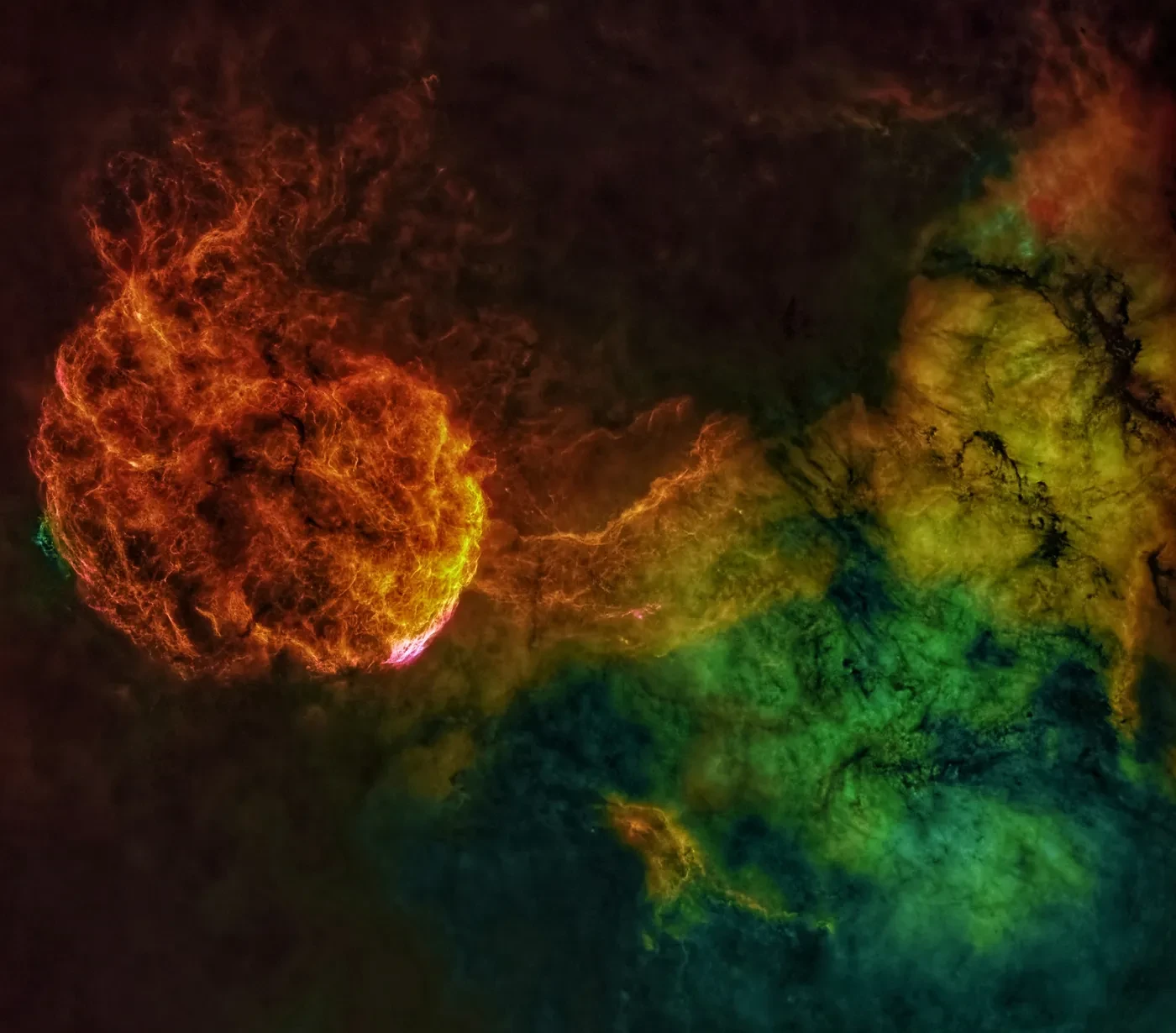

I have one, but I put it out of the category because I'm not objective. It's Marcel and Xavier's other photo, the photo of the Nebula of Hydra, which is magnificent for me. In the exhibition, I liked it a lot.

I don't remember the names of the photographer, unfortunately, but I know that there is one, it's the Moon with clouds in front. I really liked the fact that we often say in astronomy, if there are clouds, we can't do anything. Whereas in fact, we can also divert the cloud, which is a constraint, to make something very artistic.

I really liked this image. We were also amazed by all the images of the contest of young astrophotographers. We saw that there was a photo taken by someone who was 7 years old, or images of nebulae by people who are 14 years old.

When I was 14 years old, I didn't even know it existed. I find that people so young are already so passionate, it's really something magnificent.

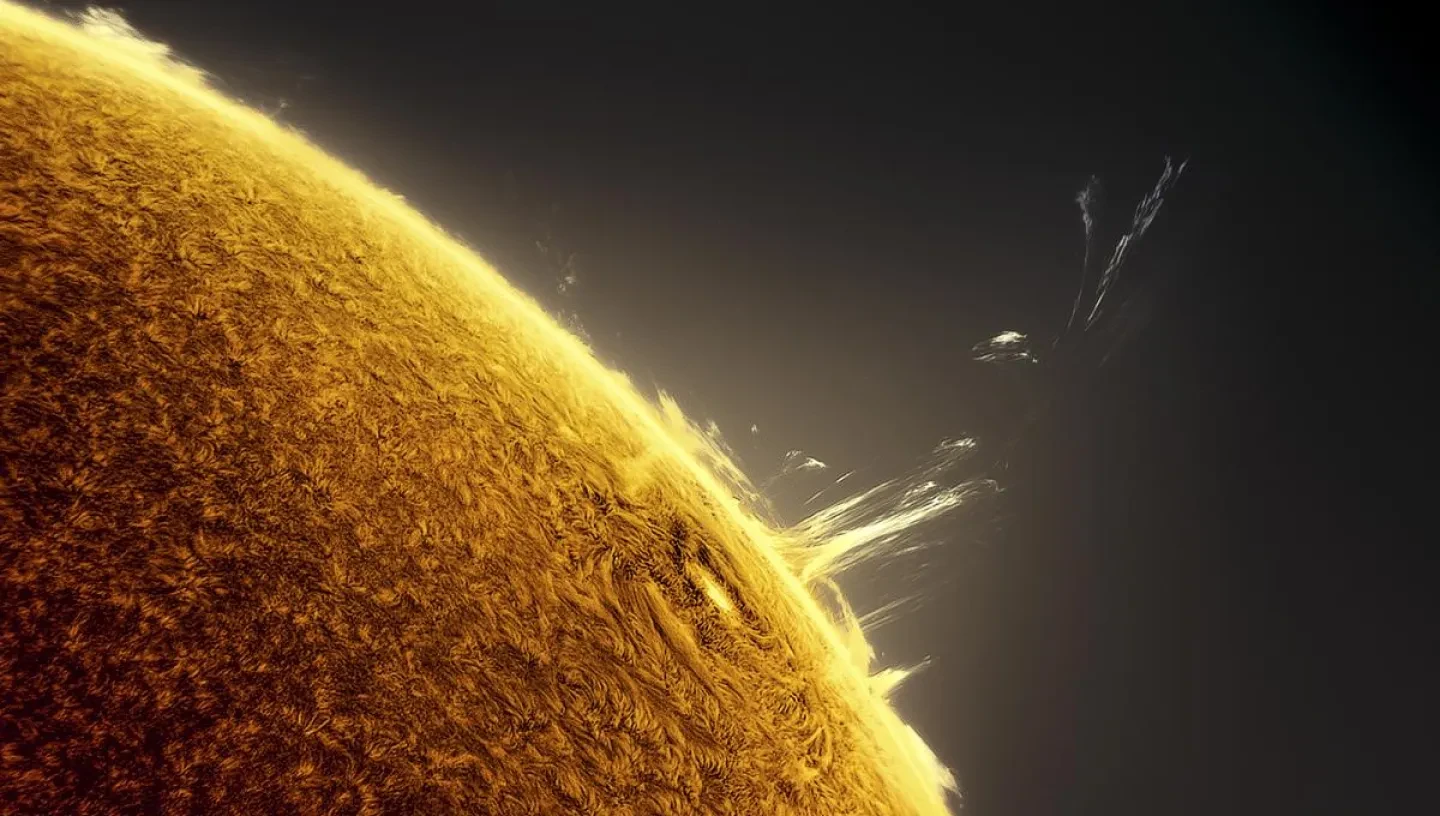

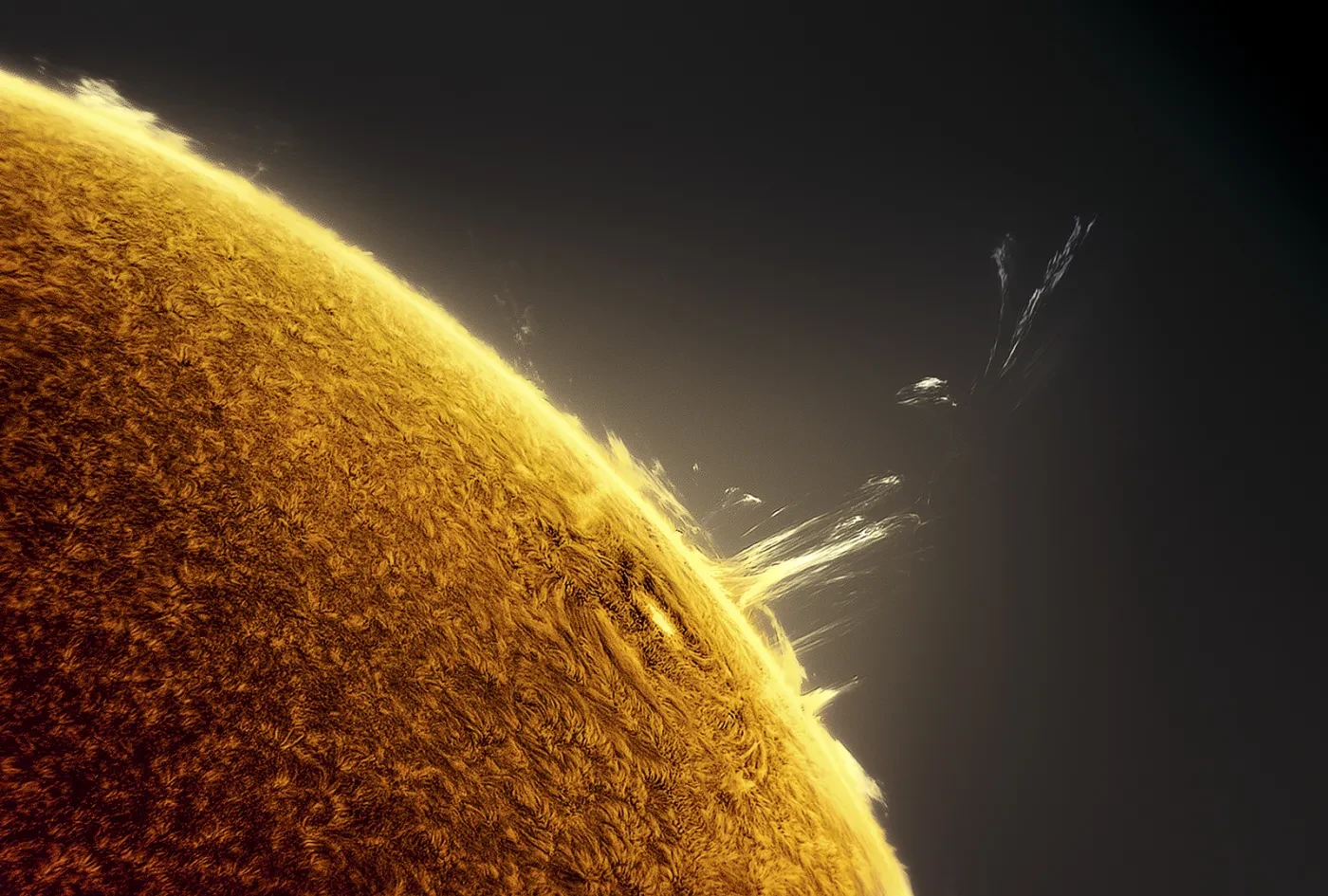

Otherwise, all the images we saw at the exhibition were incredible. And what's really good is that it covers both the planet Earth, the aurora, the Sun. So no, it was really quite an incredible exhibition.

Okay, great. I wanted to ask you, how would you advise people to go see the exhibition? I think you've just given a good demonstration of what you think.

It's really immersive, the display, each time with the author's word, the little explanation of one of the judges.

It's really good, and the images are magnificent. So yes, if someone walks by and is interested in this, or even without being interested in astronomy, I think it's not an exhibition that's specifically for connoisseurs. Someone who is a completely novice in astronomy can go there and dream, because these are images that make you dream, even if you don't have the knowledge to interpret them.

The artistic side is pure and also very beautiful.

There are certain things that you try to observe when doing astrophotography, but are there astronomical mysteries that really fascinate you, or that prevent you from sleeping at night, that you would really like to continue exploring, or that are related to photography or not in general, in astronomy? Is there something that really fascinates you?

It's not a particular phenomenon, it's really the concept of research, let's say. It's looking for something new, the concept of looking for something that no one has ever seen, and capturing it to make it visible to everyone. That's really what I think is great.

I already found it great in astrophotography, that we take things that are invisible to the naked eye and make them accessible to people who don't necessarily have the time, the equipment to practice astronomy. But in research, I find that it is still the top notch, in the sense that we are the first to take an image of something. That means that no one had seen it before, and I already find that dizzying.

And we make it visible. What I think is great is that we don't create anything. We are just passers-by, I don't know how to say, or links where these things exist, and we just make them real for the human eye.

That's really what I think is great. It's not necessarily a particular astronomical phenomenon, it's this concept of making visible what exists but we don't see.

Great. A nice poetic definition of astronomy. And again, it seems to link research, understanding these objects, making them visible and making them intelligible at the same time. Very, very beautiful. Maybe to finish, would you have any advice to give to someone who would like to get into astrophotography? What do you have in mind?

I would say that you shouldn't hesitate, you shouldn't be complex. Between what you see on the internet, photos and everything, you can't make images that are crazy at first. You have to go step by step.

You shouldn't be complex in terms of equipment either. You shouldn't say, I don't have 3,000 euros, I could never do that. Again, it's very accessible with cheaper equipment.

And don't necessarily respect all the rules. In the sense that if we had really respected all the rules, we would never have made this discovery. So I think you should first of all have fun, not hesitate to experiment with things, not necessarily want to do like this or that, but do it your own way.

I think there are as many ways to practice astrophotography as there are astrophotographers. There are basic rules, let's say, that you have to respect so as not to waste time. But there is still a great latitude of freedom.

You can take astrophotography as something scientific, we will perfectly respect the charts, the conventions for the colours. You can also very well decide that astrophotography is just artistic. We don't care about the science side and we put the colours we want.

Everyone does what they want, there are no rules. It's still an artistic practice. And if someone wants to do science, they have the right to do science.

If someone wants to do only art, they have the right to do art. So I think the basis is to have fun and that one's photo pleases oneself before wanting to please people. And as soon as we have fun, we are happy with what we do, I think it's a win.

Great, great advice. I hope it will help to inspire and make accessible the beginnings of astrophotography. It's good advice. Is there anything you would like to specify or that you would like to talk about that we didn't really touch on about this photo, the exhibition or astronomy in general? Are there any words you would like to finish on?

I have a message that Marcel gave me since he couldn't be here. If I can read it, it's great.

Of course.

Marcel says, What a crazy journey! Since we discovered this insignificant diffuse spot in the first photographic data of the Andromeda galaxy, so many incredible things have happened. We have learned a lot of new things about the Universe during our research and we have met so many wonderful people. It is difficult to express what we feel with my friends by receiving this award.

We are proud to have received so many congratulations and kind words from all over the world and we are trying to help ambitious young astrophotographers and researchers so that next year many visitors can admire the photo of another new discovery made by amateur astronomers in the museum. That was Marcel's message.

OK, well, Yann, Marcel, Xavier, thank you very much and congratulations once again for these magnificent photos.

Thank you from the whole team. It is really an immense honour for us to have experienced all this and thank you for allowing us to share it with even more people and maybe to have motivated people to embark on the adventure of astronomy. So thank you, a huge thank you from the whole team, to you, to the museum, to the whole team who organized the exhibition, the contest, to the jury, because we suspect that it must not have been easy to choose given the quality of the photos.

So it is us who are grateful for all this.

OK, well, that's great. Thank you, Yann.

Thank you very much. Thank you and have a good day.

Explore more stories from Astronomy Photographer of the Year 15

Our sponsors