Solar eclipses, whilst spectacular events to observe, are notoriously hard to photograph.

Not only is there a short window of opportunity to capture a photo, but you must also contend with a moving target, solar filters and dramatically fluctuating light levels as the Sun disappears behind the Moon.

American photographer Ryan Imperio took on the challenge during the 14 October 2023 annular solar eclipse.

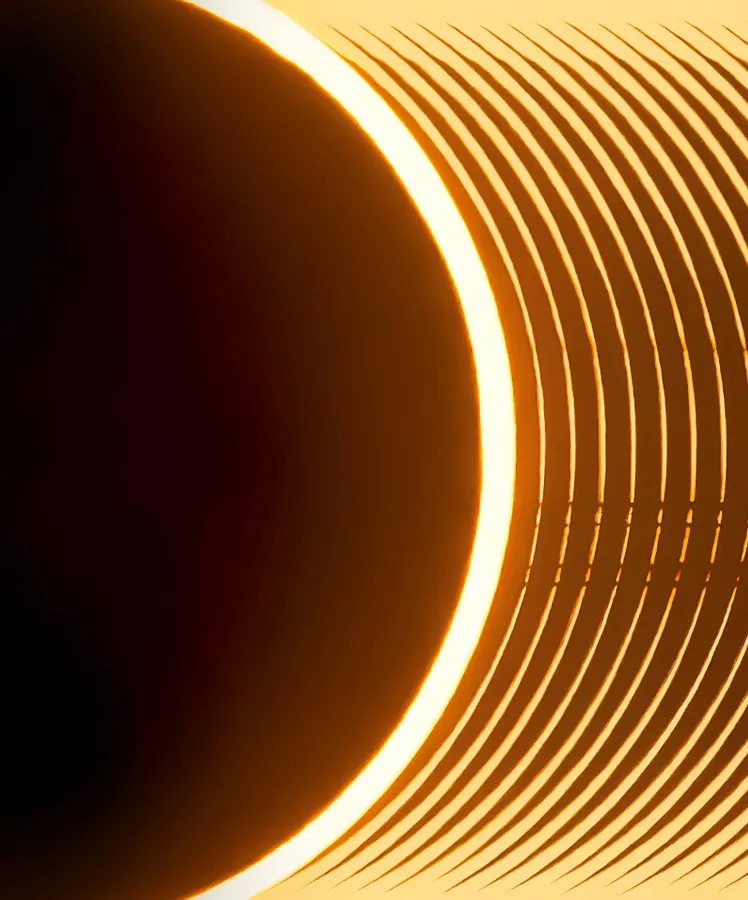

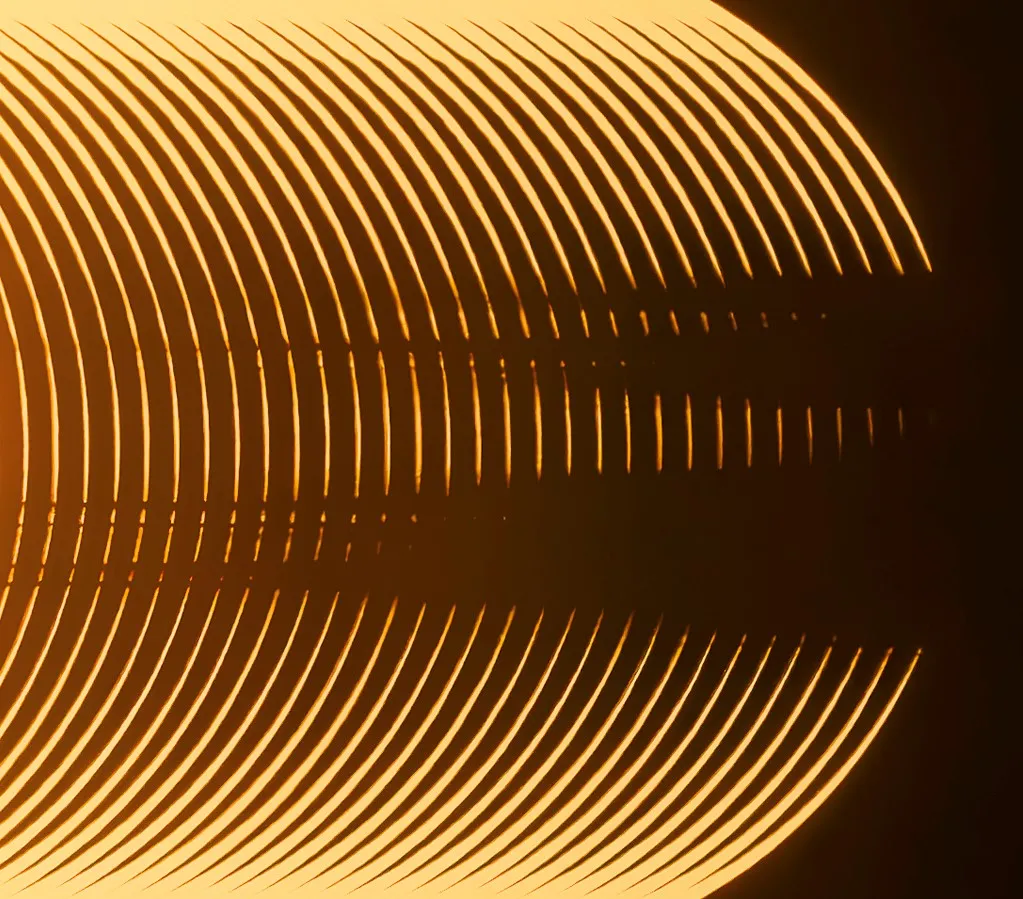

Ryan’s goal was to photograph ‘Baily’s beads’, a phenomenon that occurs when bright shafts of sunlight peek through the Moon's uneven surface.

He only had seconds to capture the beads as the eastern curve or ‘limb’ of the Moon almost touched that of the Sun, a timeframe so tight that Ryan decided to use an atomic clock for accuracy.

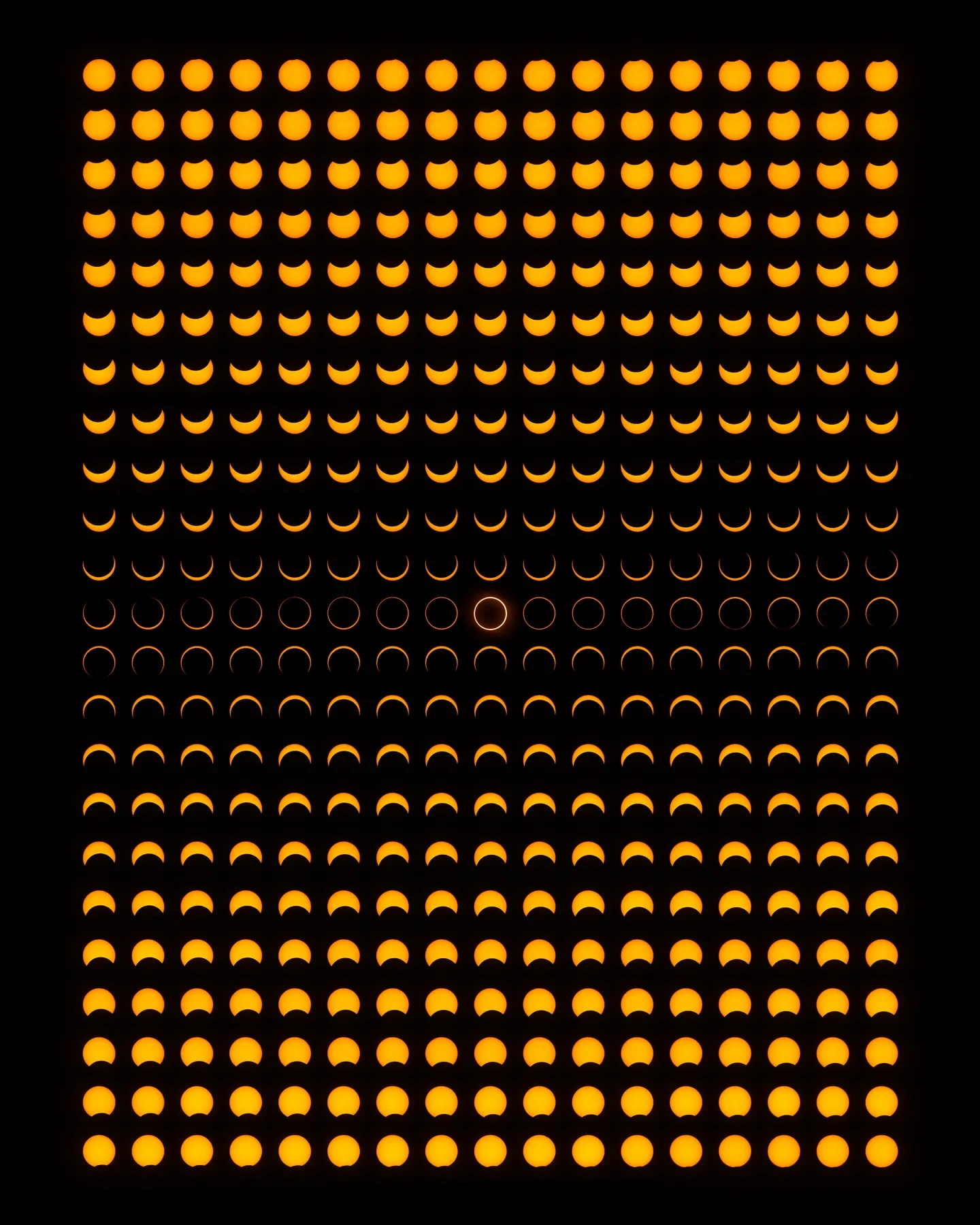

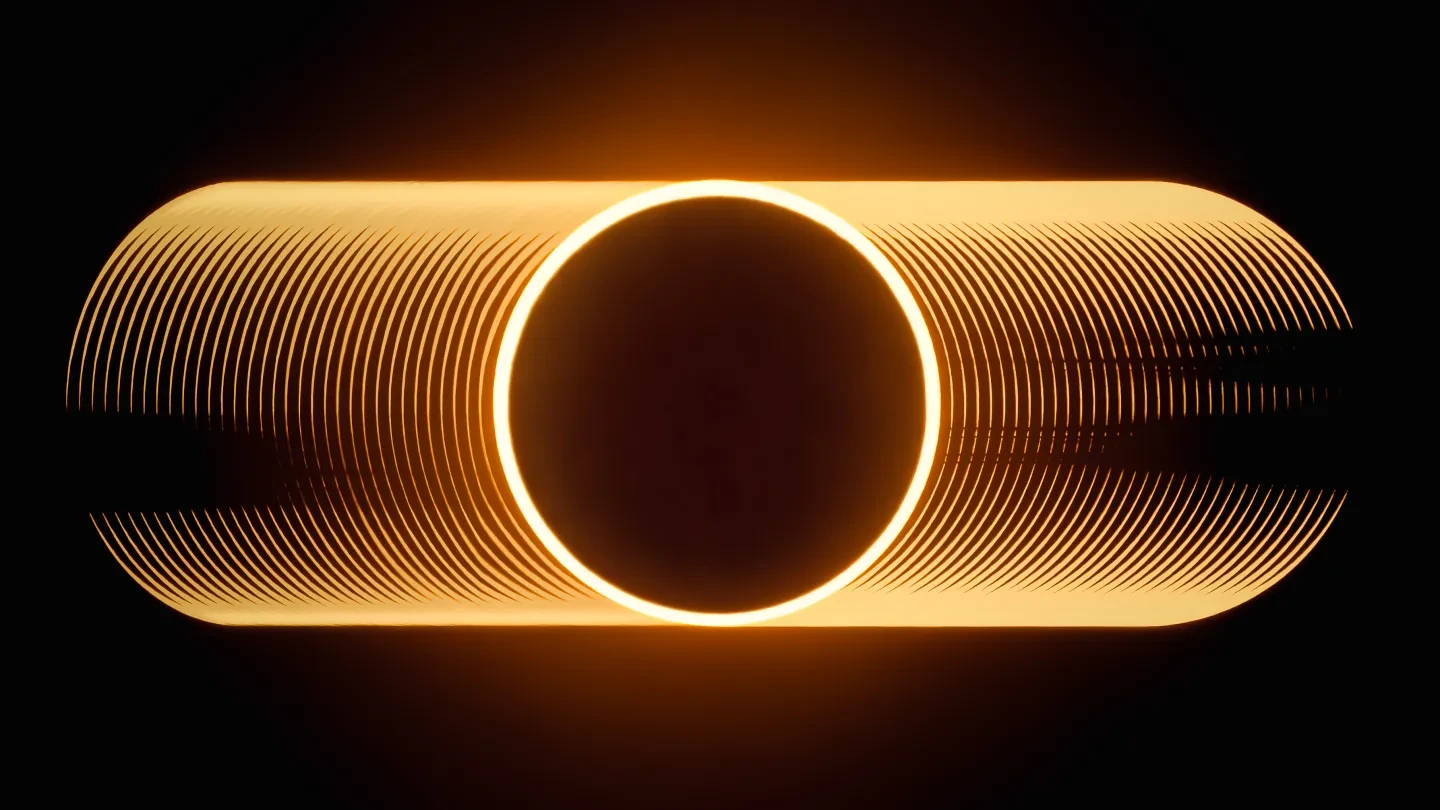

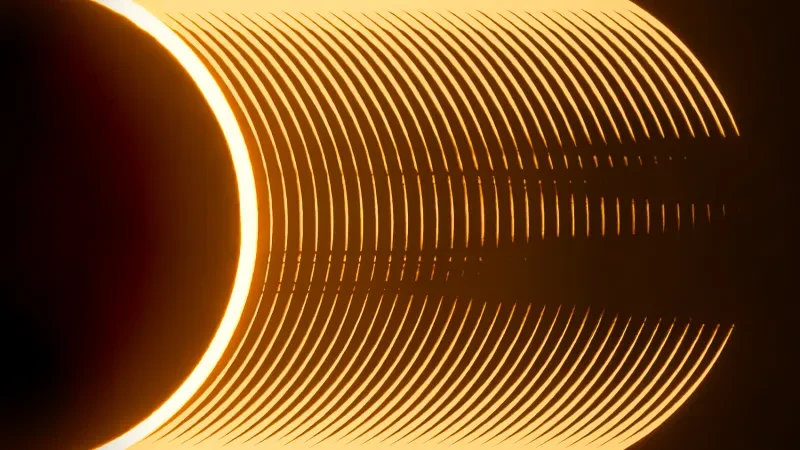

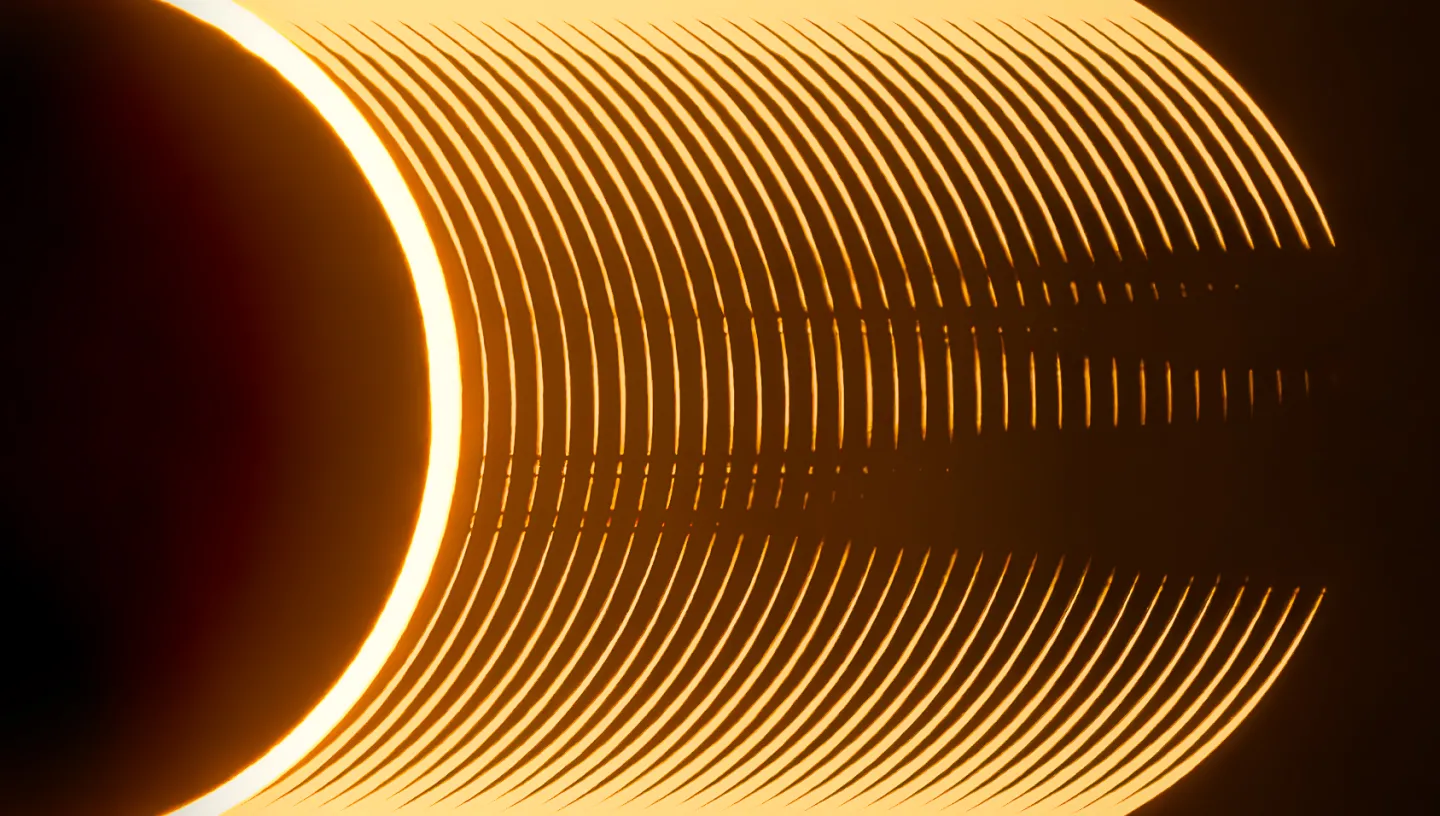

A skilful camera setup, clockwork precision, dozens of photographs and some clever processing resulted in Ryan's image Distorted Shadows of the Moon's Surface Created by an Annular Eclipse.

It was this image that saw Ryan crowned Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2024.

Find out more about Ryan's award-winning photo below, and see all the winning images for yourself at the free exhibition at the National Maritime Museum.

Distorted Shadows of the Moon's Surface Created by an Annular Eclipse

By Ryan Imperio

"What an innovative way to map the Moon's topography at the point of third contact during an annular solar eclipse. This is an impressive dissection of the fleeting few seconds during the visibility of the Bailey's beads. This image left me captivated and amazed. Exceptional work deserving of high recognition."

- Kerry-Ann Lecky Hepburn, competition judge

Annular eclipses and Baily's beads

The Moon orbits Earth in an ellipse rather than a circle. This means that sometimes the Moon is closer to us (around 360,000 km away at 'perigee', its closest point) and appears larger in the sky, while at other times it’s farther away (around 405,000 km at 'apogee', its largest distance) and appears smaller.

If a solar eclipse occurs while the Moon is farther away, from our perspective its diameter is slightly less than the diameter of the Sun. This is called an annular eclipse.

Unlike a total eclipse where the Moon fully covers the Sun, during an annular eclipse the outer ring of the Sun is still visible. This golden halo that shines around the Moon’s surface is called an annulus, taken from the Latin word for 'ring'. However, it’s more popularly known as a 'ring of fire'.

During an annular or total eclipse, viewers may also see 'Baily's beads' around the edge of the Moon. This is when, as the Moon enters and exits an eclipse, sunlight shines around lunar mountains and valleys, resulting in a bumpy or 'beaded' appearance.

A unique introduction to photography

Ryan found his way into astrophotography through a potentially unconventional route: while taking photos of the human eye and its structures for medical diagnosis and research as an ophthalmic photographer.

However, he soon took his skills outside of the clinic. “After being asked by several patients if I took photos outside of work, I decided to give it a try. Starting out just with a smartphone, I found taking pictures of nature quickly resonated with me,” says Ryan.

The hobby progressed further once he invested in some equipment: “It was in preparation for my trip to see the 2017 total solar eclipse that I decided it was time to purchase my first ‘real’ DSLR camera. From that moment I was hooked, taking photos of landscapes, sunrises, sunsets, the night sky, or anything that got me outdoors.”

A golden opportunity

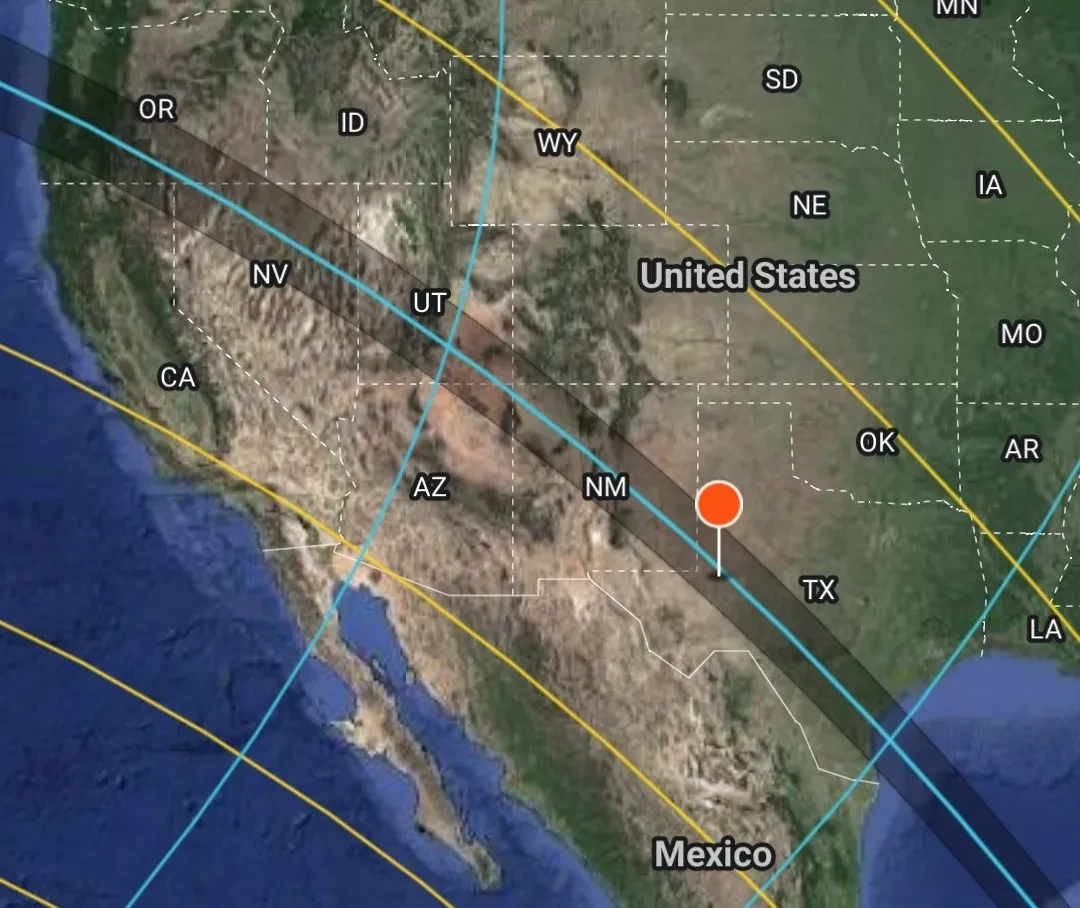

"When I found out a 'ring of fire' annular eclipse was going to pass through the United States on 14 October 2023, I knew it was an opportunity not to be missed," Ryan explains.

While the eclipse path can be pre-determined with good accuracy, the weather unfortunately cannot: for many people this rare sight is obscured behind clouds.

"The eclipse could be seen from Oregon to Texas with the path of annularity continuing towards Central and South America. Up until a few days before the eclipse I was anxiously watching the cloud forecast when my friend and I decided to book last-minute flights to Texas, which seemed to be the best option for a clear sky. We ended up in Odessa at the University of Texas Permian Basin campus."

It turned out to be a good decision: "Not only was this a great shooting location – being close to the centre of the eclipse’s path – but the school was hosting a watch party with several special events, including research balloons being launched to gather atmospheric data during the eclipse."

A different view of the same eclipse: Mission Espada by Erika Valkovicova

“My flight had a delay and I missed the connection to Austin, Texas. I arrived on the morning of the day of the eclipse in San Antonio and didn't have much for location scouting. I did my calculations at home with various applications and decided to set up my tripod at Mission Espada, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage site. Unfortunately, clouds rolled in during the maximum phase and I was quite desperate, whether I would be able to see this phase at all. Luck was on our side and when we spotted the Ring of Fire, the air was filled with screams full of excitement coming from the small crowd which gathered around this beautiful historical church. In the end, the clouds made this astronomical spectacle truly unique.”

Ryan fitted a solar filter to his lens and attached his camera to a tracking mount, which gently rotates the camera at the same rate as the Sun moves across the sky.

For a tracking mount to work the camera needs to be aligned with the celestial pole, which is difficult to do during broad daylight.

"Despite setting up the tracker during the daytime with no view of Polaris, I was able to achieve a decent polar alignment using an app and compass. I only needed to reposition the camera about every 20 minutes to centre the Sun in the frame," says Ryan.

Not being glued to the camera was ideal, as Ryan also wanted to see the phenomenon with his own eyes (protected by eclipse glasses, of course).

Viewing a solar eclipse can be a very social experience, with an incredible atmosphere generated by a large number of people observing one of nature’s most magnificent spectacles together.

“This was such an exhilarating experience!” reminisces Ryan. “There was a lot of cheering and excitement happening all at once. People were yelling and clapping with a lot of “wows”. I could hear all the cameras near me snapping away with an intense focus from the photographers. Fortunately, I had remembered to keep my solar glasses on so I could also look up and visually enjoy the moment.”

Photographing Baily’s beads

The idea for this photo was borne out of a desire to capture a moment overlooked by other photographers.

“While researching Baily’s beads, I found quite a few photos demonstrating this effect during a total eclipse; there did not seem to be as many examples captured during an annular eclipse however. Of course, this excited me in the hopes of capturing something special,” he explains.

However, the time pressure was a problem: “The challenge came down to precise timing, with a potential view of the beads lasting only seconds. The day before I researched the approximate times when the beads could be seen based on my geographical location.”

This required a level of precision beyond regular clocks and timekeeping: “As the time for annularity quickly approached, I opened an app on my phone that uses an atomic clock [a clock that measures time through the vibrations of atoms] to carefully keep track of the time down to the millisecond.

“As the Moon began passing the edge of the Sun, I intently pressed my remote shutter release with the camera set to continuously shoot at three frames per second.”

Ryan remembers the moment he realised that he had captured his target: “I received a text from my father asking if I had got it. At the time, I was still shooting regular intervals of the partial section of the eclipse to create a potential timelapse for the full event, but I briefly checked to see if I had any beads – and I did!”

It was only after uploading the photos to his computer and experimenting with the composition however that Ryan truly knew what he was working towards. “Originally I created a composite using both ends of annularity, but found the pattern most striking as the Moon was transiting out of the eclipse,” he says.

Taking the crown

“This photo shows that there is more to appreciate from an annular eclipse beyond the famed 'ring of fire',” Ryan suggests.

“I am thrilled and honoured to have been selected as the overall winner of the competition.”

Ryan adds, “Many thanks to Royal Museums Greenwich, the judges, the other entrants who elevate this contest every year, and all involved with the Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. The images showcased each year are truly inspirational.”

Ryan also hopes that he will encourage people to have a go at snapping some of their own photographs: “I hope my photo will inspire others to set out, capture, and enjoy what marvellous things our world and universe has to offer.”

You can keep up to date with Ryan's photography by following him on Instagram.